|

(2019

midterm assignment) Model Midterm answers 2019 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Eileen Burnett

March 27, 2019

Breaking It Down: The Narratives

That Move Us

Stories are an essential part of the

human experience, a part of human nature. Stories captivate us, take us to other

worlds, and provide a reprieve from what is often the drudgery of everyday life.

Rich and powerful, stories catch our

attention and force us to look forward, encouraging and revealing answers to the

most basic of humanity’s questions, such as: Where are we going? And what does

our future hold? Within this class, three types of narrative models unfold,

creation apocalypse, evolutionary, and alternative, each revealing to us the

frameworks that build such stories of renowned, ranging from scriptural texts

like The Bible to H.G. Wells’ The Time

Machine. Each of these three categories, in turn, is made up of unique

characteristics that deal with some important questions of epistemology, time

and its relativity, and humanity in vastly different ways.

Structures like creation/apocalypse deal with the

implication that though humanity’s situation was once good, due to outside

influence these things have changed and now require a remedy. evolution, and

alternative narrative forms. We are

drawn to apocalyptic literature for the same reasons we gravitate towards

narratives of adventure in video games- to be a part of something bigger,

something ancient, and something over which it is possible to prevail, breaking

us out of the mundaneness of reality and catapulting us into the fantastical. In

the Biblical narrative, specifically the first book of The Bible, the Book of

Genesis, humanity is portrayed as having been in a utopian state at

its inception, but as a result of this outside influence (Satan in the form of

the serpent, “more subtil than any beast of the field” (Gen 3:1)) mankind is now

relegated to hardship and frustration. The last book of the Bible, the

Book of Revelation is the apocalypse

part of the narrative, flip side where restoration comes through a great

cataclysm. At the behest of God the Father, the angels in the throne room begin

to play trumpets, pour bowls and vials, and proclaim “woes” to the inhabitants

of the earth, revealing to humanity “the fierceness of his wrath” (Rev 16:19),

and thus cleansing the earth and restoring it to perfection.

But this is not the only story that falls under this

narrative style. Clark Omo comments on Octavia Butler’s

Parable of the Sower, citing its

similarity to “the story of Genesis from the Bible, along with its Apocalyptic

counterpart, Revelation” for reference. Within

Parable, Butler weaves a similar

framework, where an economic crash leads to a dystopic future. Lauren, the main

character of the story, embarks on a quest to return to and Eden-like lifestyle

through her cult of Earthseed, whose cryptic scripture dealing with God as

change overlay the structure of the book. “It focuses attention, strengthens

purpose, and unifies people” (214) Lauren writes. This desire to return to the

way things once were is a classic example of how

Parable illustrates the

creation/apocalyptic narrative. Both stories occur within a reasonable and

easily acceptable linear timeline, espousing more traditional, if not also

conservatively religious- values, using similar symbols for commonly held ideas,

such as gardens, the theme of redemption, and the overwhelming pressure of

decline.

Literature of the future can also fall within more than

one category. According to Timothy

Morrow, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower,

H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, and

the short story “Stone Lives” fall into this dual category, encompassing

not only the traditional apocalypse/creation narrative, but also delving into

the evolution style, which values scientific knowledge and its pursuit over any

other form of acquisition. Pragmatical and calculating in its approach, the

evolutionary category is also distinctively different from the

apocalypse/creation narrative in that the timeline is often set in terms of a

cyclical cosmic scale, often taking into account events that occur over a period

of millions of years. Parable is a great example of this blending of the

apocalyptic and evolutionary narratives, as it takes the reader from a present

cataclysm to a time to hundreds, maybe thousands of years into the future

through Lauren’s idea for her new religion, Earthseed. Her plan is for it to

spread across the solar system, even galaxies, in an interconnected network of

an evolved humanity.

Evolution also works

within species, as in the case of “Bears Discover Fire” by Terry Bisson. In this

story, bears evolve beyond the lumbering, forest-dwelling creatures of old to a

species that learns how to use fire. To the main character, his mother, and his

son, Wallace, Jr., these bears have formed a human-like society, full of family

structures and community, just like us. “The big bear” Bisson writes, “tended

the fire, breaking up the dry branches by holding one end and stepping on them,

like people do.” This parallel of bears and humans draws on the intellectual

concept of Darwinism, an essential component of the evolutionary model. Social

Darwinism is often the mode of human interaction, and Bears plays into

this standard flawlessly, making it both an interesting and appealing read.

The final category

for future narratives is the alternative future, of which H.G. Wells’ The

Time Machine is a prime example. Alternative timelines work because they

operate on the premise that the actual act of creating the ideal is in fact the

ideal itself; that is, when placed in a situation where actual perfection is

reached, this attainment gives most people a disconcerting feeling, akin to a

loss of hope. People want to know that there is something more to hope for.

Wells utilizes this fact when he merges the evolutionary with the alternative

narratives, specifically in his descriptions of the species inhabiting the

earth. Wells paints the picture of a Marxist segregation of communities that

lead, 800,000 years in the future, to the formation of the Eloi, the former

upper class of humanity who, due to excessive leisure and lack of stimulus, have

evolved into a childlike, simple-minded sort of creature, unfazed by need or

suffering, and the Morlocks, the lower, worker class of citizens who devolved

into a subterranean, animalistic form which preyed upon the sheep-like Eloi for

sustenance.

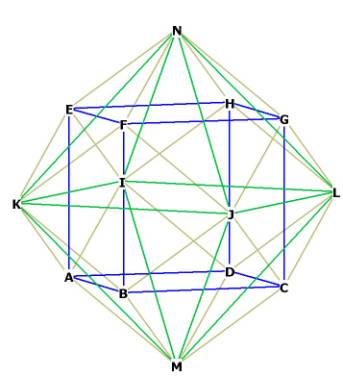

In

like manner, “The Garden of Forking Paths” by Jorge Luis Borges imparts

alternative realities through the labyrinthian layout of the book within the

story as infinite universes in itself. “An invisible labyrinth of time” (40)

Borges calls it, one in which an infinite amount of possibilities unfold before

you, creating layer after layer of potential truths from which any number of

reflections and permutations can occur. Borges capitalizes on the complexity of

the mind, the ever changing and branching myriad of choices that lay before us

as humans, condensing the ideas to a single book. Alternative timelines do not

operate in the typical linear fashion as the previous two models, and is

therefore much more convoluted and mystical in nature.

Stories can fall into one or several of these categories, adding richness and flavor to the narratives that are unique to this category. Stories like Genesis and Revelation from scripture exemplify the creation/ apocalypse narrative in that they give hope for a better future through a trial by fire. Tales of evolution such as Parable of the Sower and Bears Discover Fire tell stories of growth, showing us what we one day might become. And alternative Narratives like The Time Machine and Garden of Forking Paths lead us into strange and new places, warning us of the consequences of even the smallest of actions. Within these three categories, therefore, are captivating stories that answer profound questions of where we are going as a humanity, bringing a sense of peace, that at least these stories are not in our visible future, and that we still have time to make something of it.

|

|

|