|

(2017

midterm assignment) Model Student Midterm answers 2017 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Clark Omo

Futuristic Anxieties: Examining the Exploration of Fear and Anxiety in

Literature of the Future

At

this point in the semester, the selected Literature of the Future has so far

covered three narratives of the Future: Creation/Apocalypse, Evolution, and

Alternate History. For Creation/Apocalypse, we were introduced to this narrative

through the Books of Revelation and Genesis, along with the novel,

The Parable of the Sower. For

Evolution, we explored H.G. Wells’s The

Time Machine and “Somebody Up There Likes Me”, and for Alternate History we

were given a variety of short stories such as “Mozart in Mirror-shades” and “The

Garden of Forking Paths”. Though varied greatly in approach to each of these

individual subjects, all of these stories, as well as the narratives, have

something in common; they all approach and examine anxieties and fears

concerning the future, and thus reflect the dread that overshadows the

consequences that accompany present decisions. For Creation/Apocalypse, the fear

is that the current state of civilization is in decline, and thus will reach its

terminus in the form of total destruction. For Evolution, there is hope that man

will eventually find a way to evolve out of his current dilapidated state to a

point of utopian perfection, yet at the same time certain crucial and beneficial

traits will be lost. And for Alternate History, multiple choices and

possibilities are presented at once within the same instantaneous moment of

time, yet there is no way as to determine which one is the best. Throughout all

three of these narratives exist this fear of the unknown, and this fear is what

guides these narratives, as well as explains their purpose within the chosen

stories.

The

Creation/Apocalypse Narrative explores this fear in the most blatant way: the

Apocalypse. This Narrative follows the pattern as such: man is created and given

residence with a perfect and serene environment, not at all under threat from

decay or corruption. However, this peaceful state is soon violated and

decimated, resulting in the current state in which the protagonist finds him or

herself, and then is capped off by a purifying event of total and mass

destruction. The fear experience in such a narrative is readily apparent, and

can be seen in such works as Revelation, where the entire book consists of

nothing less than fire and judgement, and at last perfection at the end. This

idea, of course, creates anxiety: will there be such an Apocalypse, are we in

such as state of decline that would justify an event like this, and (perhaps

most importantly) is there hope? Revelation says there is, and it comes in the

form of the New Jerusalem. Similarly, The

Parable of the Sower also follows this Creation/Apocalyptic Narrative, in

which it also looks forward to state of utopian safety. As the story begins, the

audience is introduced to Lauren and her town that just so happens to be

isolated from the decay outside (gangs, bandits, etc.), much like a sort of

Edenic Paradise. However, the state of this paradise is far from secure:

countless times does Lauren express her concern that their situation is only

worsening. As Lauren admits to her

father, “It’s getting worse, Dad” (66), to which her father replies, “I know”.

Both Lauren and her father know that the end will come eventually; that the

world around them will be shattered and they will have to find the ways and

means of survival in a tremendously unsafe and insecure world. Clearly there is

anxiety in such language and responses: fear of the oncoming apocalypse.

This

anxiety regarding future consequences is also present within the Evolution

narrative as well. The Time Machine

illustrates such fear of the future as thus when he travels some several

millennia forward into time to find man rendered into a class separated society

dominated by two distinct groups: the Eloi and the Morlocks. The Eloi, as the

Time Traveler observes, are passive and meek: the future of human evolution, as

the Time Traveler at first concludes. Yet, conversely, the Eloi’s representation

as a future stage of human evolution is not an appealing one; for instance, they

lack even the smallest inkling of sympathy for those of their own race,

evidenced by how they watch with disinterest as Weena rushes to her death in the

rapids of the river. The Time Traveler, in the later course of the story,

discovers that in fact the Eloi are serving as nothing more than “cattle” to be

nourished so they can function as “fatted cattle”, so to speak, by the Morlocks

who then make a meal from their flesh. As a result, the Eloi live in terror of

dark places and the night itself. Interestingly, in contrast, the Morlocks

themselves have an extreme fear of light. Humanity in

The Time Machine may have evolved to

some extent: the Eloi’s environment does seem peaceful and without need for any

major sort of technology to aid in living (at least superficially). But this

evolution has also left them weak and devoid of care (one may dare say they are

without Love, to an extent). Evolution, therefore, does not promise progress in

its cyclical progress: it also brings with it devolution, evidenced by

The Time Machine. This is anxiety,

for even though man may continue to “evolve” into a better and more perfect sort

of being, we are just as likely to lose the most basic and essential

characteristics that define us as humans.

The

story “Somebody Up There Likes” me also expresses a fear of the future, even

though technology is evolving and advancing. The protagonist of this piece,

Dante, laments regarding the evolution of his own students, “My students

implanted digital watches in the skin of their wrists, tattooed and barbered

themselves so as not to appear human…” As the world advances around him, Dante

is steadily becoming disconnected and the definition of what it means to at

least appear human is being changed.

The anxiety regarding the future is clear in this story, for as society and

culture seem to advance before eyes, those thing that may been better are in

danger of being lost. This is what Dante feels, but even he realizes that the

advancements may not all be bad, for he does succumb to obtaining a Revelation

2000, the newest and most hi-tech computer on the market. Yet, still, some

things are being lost, and Dante feels, as some of this story’s audience must

feel, as though things are slipping away.

The

consequences of such advancements (which is another branch of this anxiety

regarding the future) is also explored through the Alternate History narrative.

The story “Mozart in Mirror-shades” illustrates this anxiety with future

decisions well, for its own setting is one of multiple realities where different

decisions are made. Rice (the protagonist) lives in a world where his own

timeline has run out of oil, and thus the powers that be have decided to go back

in time and crossover to alternate realities where there is still oil. The

reality they have chosen is in fact one where Thomas Jefferson obtained the

title of being the first President of the United States, opposed to George

Washington. And throughout this story we are assaulted with images of the

consequences of making such a decision as taking the resources from a separate

timeline. There are protests led by Comanches against oil derricks, and a Marie

Antoinette that yearns for a bikini. Mozart himself is altered as well, to the

point he has no interest in making music. This series of events and alterations

serve as reflections of the infinite amount of possibilities that face humanity

regarding its future. Each decision has in turn an effect, and each effect, in

turn, has a consequence. And it is these consequences that frighten humanity,

for, since our knowledge is infinitely limited, we can never know whether the

decisions made now are truly the ones that will bring the most benefit. There

could be unforeseen consequences to everything ever thought or done. Thus, the

world of “Mozart in Mirror-shades” is fraught with rebellion, exploitation, and

bizarre anachronisms: the results of choosing to alter one timeline’s past in

order to save another’s future.

Speaking of paths, another story that explores this narrative as well as the

fears and anxieties held within it is the “Garden of Forking Paths”. In this

story, the audience is looking through the eyes of the protagonist, a spy for

the Germans during WWI, on assignment in Britain. Once the spy runs from his

pursuers and eventually arrives in the home of Dr. Stephen Albert, the audience

is given another glimpse into the possibilities and consequences making separate

decisions. This story, however, takes a more theoretical than physical approach

compared to “Mozart in Mirror-shades”, though it nonetheless expresses the same

anxiety so far covered in this paper. As the protagonist converses with Dr.

Albert, he learns that the Doctor has in his possession a volume of the work,

The Garden of Forking Paths, written

by the protagonist’s ancestor. In this book, multiple fates and actions are

illustrated for the story’s hero; as the protagonist relates, “in the third

chapter the hero dies, in the fourth he is alive.” Thus, this book examines the

possibility of alternate futures, with each future hinged upon the decisions

made by the central character. And to complicate things even further, the book

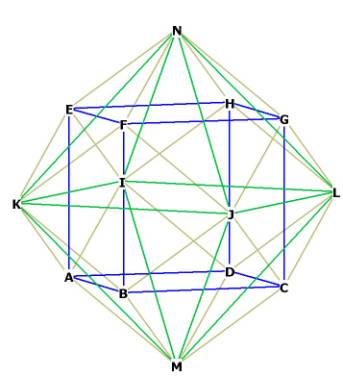

does not simply present each alternate future as a possibility, but rather as a

kind of branching network where every

future happens at once.

This

is mind-blowingly complex from just a critical standpoint upon narrative. To

think of experiencing all the possible consequences of our actions and every

future they would result in within the same and single moment of time is as

staggering to the human mind as it is reflective. Would knowing all our possible

futures have any sort of influence upon how we make decisions? It seems so for

the protagonist, for as Dr. Albert explains: “…in one of the possible pasts you

are my enemy, in another, my friend.” And so, the protagonist later shoots

Albert out of response to this very possibility. And then, as the story ends,

multiple futures unfold for the protagonist at once: one where he is arrested,

another when he is successful in his mission. As demonstrated by the “Garden of

Forking Paths” there exists an anxiety within the truth that one action could

have multiple consequences, depending upon which path one follows. Such is the

purpose of the Alternate History Narrative: to explore the possibilities of what

would happen if humanity’s decisions as well as history had taken a different

course, thus reflecting the anxiety and fear of what could (or even

should) have happened.

The

three Narratives of the Future certainly explore what they are named for: the

future. And by doing so, they explore the fears and anxieties often associated

with what may come to pass. For Creation/Apocalypse, there is the fear of the

Apocalypse itself. For so it seems that, even when allowed to exist within an

initial state of perpetual perfection and peace, corruption and inevitable

destruction do come. As Eden was perfect, it fell to the wiles of Satan. Same is

true in The Parable of the Sower.

Though Lauren lives in a place that is not totally safe, it is nonetheless

Edenic with its promises of protection and preservation of family. Yet, its very

walls come crashing down in fire, redolent of the Last Days in Revelation. This

same fear is present in the Evolution Narrative as well, such as in

The Time Machine where the Time

Traveler travels to time where humans seem to have evolved out of their own

humanity. And furthermore, the Alternate History Narrative explores the same

fears, for it presents its audiences with the possible consequences if decisions

had been made differently. Such is the state of Literature of the Future:

literature of ideas regarding fear of the future. And thus, by exploring these

fears, we who dare read these works see manifest the dark fact that, truly, the

future is by decree unforeseeable.

|

|

|