|

(2017

midterm assignment) Model Student Midterm answers 2017 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Katie

Morin

10/10/2017

Destiny Defined: Analyzing Narratives of the Future

As someone who had yet to study the genre of futuristic literature, I was

surprised to discover just how complex the genre truly is. Works of the future

are multifaceted and can generally be grouped under one of three storylines:

creation/apocalypse, evolution, and alternative futures. While these are just

the three primary narratives of futuristic literature, these groups are not

entirely exclusive of one another, and it is not uncommon to notice elements

from one storyline present in another. Over the course of the semester, I have

gained a deeper understanding of each of the three storylines, and a newfound

appreciation for futuristic literature as a whole.

The creation/apocalypse narrative has a linear timeline, with a clear

beginning and end. This is largely attributed to Judeo-Christian ideology, which

brings to us the concepts of Alpha/Omega, beginning/end, and Genesis/Revelation.

According to our course’s website, as a storyline, this linear “model conforms

to Aristotle (Poetics VII) that a plot or narrative must have ‘a beginning, a

middle, and an end.’” It is a straightforward timeline which most people have

some level of familiarity with. However, in some instances, this linear model

can become a bit more complex as it can appear somewhat cyclical—for example,

certain aspects from “the beginning” or Creation reappear during “the end” or

the Apocalypse. For instance, union with God is first seen in Eden’s utopia, and

also later in The Book of Revelation, where we read of Heaven’s own reunion with

God. As discussed in class, another example of this cyclical pattern is

Genesis’s Tree of Life also making a return appearance in the book of

Revelation.

When

considering the Bible, Genesis marks the beginning of Creation, while Revelation

both begins the formation of a dystopia (the Apocalypse), and later in chapters

21-22, the beginning of a utopia: Heaven. A utopia is a society where everything

appears to be running smoothly, and all of its members are seemingly

happy/content. In contrast, as defined by our course’s website, a dystopia is a

“society opposite from a utopia, a utopia

gone dysfunctional, or the world just before an apocalypse or ‘left behind’

after one.” In works of the future, dystopias appear to be far more common than

utopias. A prime example of a dystopian/apocalyptic society can be seen in

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower.

In it, the story’s protagonist, Lauren, finds the world around her

self-destructing—the government is corrupt, water is scarce, fire is rampant,

and violence has her world in ruins. It is the start of the apocalypse, the

beginning of the end, whether Lauren is ready for it or not.

In contrast, the second type of futuristic storyline, the evolutionary

narrative, appears to emphasize free will and adaptability. Only the strong

survive, and evolution is necessary in order to stay alive. Although

Parable of the Sower falls under the

creation/apocalypse narrative, Lauren herself exhibits characteristics seen in

the evolutionary narrative. The world as she knows it is ending, but she takes

it upon herself to evolve/adapt to her new normal. She begins to form Earthseed,

her own religion, and Lauren repeats over and over that “God is Change”—she is

ultimately able to save herself by evolving as an individual. Lauren also serves

as an example of our course’s definition of evolution (evolution = change +

continuity), as indicated by Karin Cooper’s midterm, “The Alternative Evolution

of the Apocalypse” (2015). Cooper writes that while the group Lauren creates is

new, Earthseed still resembles the community in which she was raised. Cooper

argues that Lauren’s formation of a new group still falls “within the bounds of

the evolution narrative because while the community she starts has similarities

to the one she came from, it does have changes that make it more able to survive

in the new environment in which it was founded.” While she still maintains

certain aspects of the life she once led, Lauren must adapt and evolve in order

to make it in her post-apocalyptic world.

“Stone Lives” by Paul Di Filippo exemplifies the evolutionary narrative in a

more obvious way, where the protagonist, Stone, is blinded, then given a new set

of bionic eyes, and introduced to a new world of technology. In order to survive

the post-apocalypse, he must learn to adapt/evolve to his new surroundings, much

like Lauren does in Parable.

Similarly, “Bears Discover Fire” by Terry Bisson is also classified as an

evolutionary narrative, although far more primitive and less technological than

“Stone Lives.” In it, bears have evolved

to the point that they are fully capable of starting fires, and can also

interact with humans without behaving aggressively, possibly another example of

their growth as a species. However, apart from these more obvious signs of

evolution, the short story also features less obvious signs of evolution, such

as the protagonist’s hesitancy to upgrade to radial tires, which is reiterated

time and time again, presumably to emphasize the changing times.

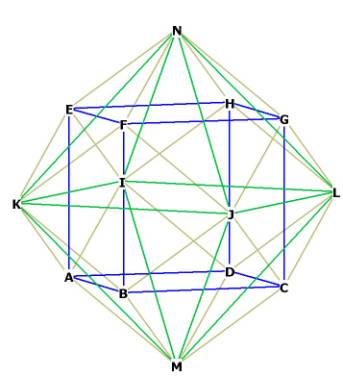

Finally, the last narrative, alternative future fiction, is likely the strangest

of the three subgenres. Concerning alternative futures, our course website reads

that “according to postmodern quantum physics or relativity, time travel and

multiple strands of time are theoretically real or at least probable.” It goes

on to state that because of this strangeness and all that comes with it

(“multiple universes, parallel worlds, time portals, worm-holes”), alternative

future narratives might appear to be “far-fetched” to some, but this is not

necessarily a bad thing, as some may find the uniqueness of the genre to be

appealing. H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine

is an example of this genre, as it explores time travelling. This narrative is

especially interesting, though, because it is also an evolutionary narrative

following a linear timeline which allows the Traveller to witness the growth and

decline of the world as he transports to and from different time periods both

before and after the one in which he resides. And although it does seem

unrealistic at times, there is some level of relatability as the Time Traveller

has almost humanlike interactions with the majority of the creatures he

encounters (the Eloi and the Morlocks), and does not divulge too much

information concerning strange organisms he discovers (such as the giant crabs

or octopus-like creature). This stands in agreement with what we have discussed

in class, where in order for a work of science fiction to be not only

interesting, but convincing, there can only be one “unbelievable” or “magical”

component (in this case the time machine itself), and all of the rest should be

relatively believable, hence why the Traveller could not possibly interact with

the foreign creatures any more than what has been described, simply because it

would have become far too far-fetched and unbelievable.

Believability is an issue which arises in each of the narratives that we have

covered, save for one. “Better be Ready ‘bout Half Past Eight” by Allison Baker

is one of the pieces that I found to be most interesting simply because it is

not one that I would have initially associated with any of the three genres, let

alone alternative future. In it, the story’s protagonist, Byron, struggles with

the realization that his lifelong friend, Zach, is transitioning to “Zoe,” and

as the story progresses Byron begins to internalize her plight, and experiments

with makeup, transforming himself into a woman for no particular reason. At

certain points, he also has conversations with his deceased mother, and as he

struggles with his own identity, seems to take on his mother’s as well. Although

this narrative may not appear to be as much of an alternative future narrative

as The Time Machine, it still meets

the criteria of the genre as the characters struggle with which paths they

should ultimately take, and subsequently dictate their own futures.

|

|

|