|

(2017

midterm assignment) Model Student Midterm answers 2017 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Tanner House

11/6/2017

Comparative Futures (Essay 1)

When

discussing the “literature of the future”, it is absolutely necessary to

acknowledge the fears, concerns, and anxieties of both the past and present.

Without the context of where we are and where we have been, speculating about

the future of humanity becomes a pointless exercise in futility, grounded in

nothing but the fantastical. Former student Tom Britt’s 2016 pre midterm essay

“A Gift to the Dead and a Warning to the Living” affirms this notion of the

necessity of the literature of the future to be grounded in the context of both

the past and present. Necessities, however, can be problematic, as the idea that

literature MUST contain something seems to limit the very scope of literature.

If topics must be covered, and universals are established, then visions can be

compromised. Literature of the future addresses this concern in the form of

multiple distinct, concurrent narratives: the creation/apocalypse narrative, the

evolution narrative, and the alternative future narrative. These narratives are

all concerned with similar issues, but they take different approaches to said

issues, creating a discourse in which we can discuss the future through a

variety of different, but equally valid, interpretive lenses.

The

creation/apocalypse narrative and the evolution narrative are the two visions of

the future which are most directly concerned with the issues of the past and

present. Creation narratives, by their very definition, have to consider the

context of humanity’s past. If we wish to explore where we came from, we must

acknowledge where we have actually been. One of the biggest themes in

creation/apocalypse narratives is the concept of revelation, or the idea of some

sort of ultimate understanding divined through the intervention of the

supernatural. This concept is fully on display in the scriptural texts covered

in the course. Genesis and Revelation (particularly Revelation) are the word of

God himself, and offer a vision of humanity’s beginning and end. Genesis begins

with “The Creation” itself, and simply states that “In the beginning God created

the heaven and the Earth.” As

Genesis progresses, God begins to give shape and from to the dark void which

originates from his creation, and man is shaped in the image of God. This

conception of the creation narrative is one of the most fascinating texts that

we have, as it outlines the processes of creation in which a God who is the

invention of man invents man in the image of himself, an image which was created

by man in the image of itself. In essence, we made God in our image, who in turn

made us in his image. This paradox of creation has been one of humanity’s

longest lasting fascinations, and our inability to understand from where we

truly came has in turn led us to constantly wonder how we will end. Revelation

details the process of our end, and this is demonstrative of the linear

narrative structure that is typically associated with the creation/apocalypse

narrative.

Many of the themes present in these

scriptural texts are reflected in Octavia Butler’s

Parable of the Sower.

Parable parallels many of the

concepts of a more traditional creation/apocalypse narrative but also

simultaneously introduces concepts associated with an evolutionary narrative.

These narratives are valid, but they are lacking in empirical evidence, leading

to subjective interpretations which can weaken the strength of their arguments.

On the other hand, evolutionary narratives are often directly concerned with the

empirical. Evolutionary narratives have their own sort of revelations, but they

are divined not through the supernatural but the empirical. Their claims are

based on observation, and assert that the story of creation, and destruction,

resemble structure like circles and spirals. According to the evolutionary

narrative, humanity’s beginning, and its demise, can be traced through objective

and empirical evidence. Evolutionary narratives also carry themes and ideas that

reflect the concept of Social Darwinism, or the idea of the “survival of the

fittest”. Here, Parable merges the

creation/apocalypse narrative and the evolutionary narrative. The apocalypse has

come and wiped out the previous way of life, but now new social structures have

taken hold as the strongest of humanity’s survivors have risen up to create a

new world. Life springs from destruction, and evolutionary forces come to the

forefront in the creation of the new world.

A

similar process occurs in H.G. Wells The

Time Machine, in which an apocalyptic event takes place, wipes out humanity,

and paves the way for new forms of life to grow and eventually dominate the

remnants of the earth. Time Machine

is far more concerned with evolution than

Parable, however, as it directly addresses time on the cosmic/geologic

scale. The Traveler moves thousands of years into the future, and comes to a

point in time where humanity is not even a memory of time but just a simple

speck on the timescale, long extinct and forgotten. This narrative style allows

Wells to explore the future without the pretext of human influence while

simultaneously establishing that certain distinctly human ideas and conceptions,

like civilization and economics, might be inherent and necessary for sentient,

conscious communities to exist. If

Parable merges the creation/apocalypse narrative with the evolutionary

narrative, then Time Machine merges

the evolutionary narrative with the final narrative we have covered in the

course, the alternative future narrative.

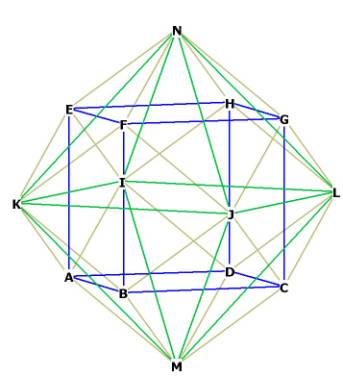

The

alternative future narrative takes ideas and concepts from the other two

narratives to create a sort of far more flexible hybrid narrative. Alternative

future narratives combine the empirical and supernatural in order to form a

better-rounded and complete vision of the future, often explaining their

chronology through things like alternate dimensions, forking paths, and parallel

worlds. A number of our texts have depicted alternative futures (The

Time Machine, “The Garden of Forking Paths”, “Mozart in Mirrorshades”) and

these texts all contain some conception of time as a maze/labyrinth/spiral,

often delving into subjects more traditionally associated with theoretical

physics, like worm holes, time spirals, and alternate or parallel dimensions.

The theoretical and more open ended conventions of these narratives often allow

them to more freely discuss and experiment with many of the concerns of

literature of the future. By not limiting themselves to specific structures,

alternative future narratives are enabled to bore completely explore future

concepts that themselves are difficult to define with structures, like culture

and gender. These narratives are also often far more experimental and playful

than their counterparts, as they deal with concepts and ideas that do not

necessarily translate very well into the sometimes too serious discourse of

traditional, “high” literature.

Allowing Mozart to exist as a time travelling, reality warping antihero is not

something that many other forms of the medium are allowed to do, but the

alternate future narrative enables its authors to do just that, disregard

expectation and practicality in favor of exploration and discovery.

These

three conceptions of the narratives of the future that make up our course all

carry with them distinct characteristics and qualities, and yet the most

effective and memorable texts which we have studied often combine or blend

aspects of all three of them to create more well-rounded and complete visions of

the future. The necessity of convention in defining mediums and genres is almost

thrown out in the discourse of literature of the future, as the subject itself

is one that defies convention. Any narrative of the future is ultimately going

to be an exercise in speculation, and the realm of speculation is infinite.

These narratives allow us to explore and navigate that realm, and by attempting

to define or predict the future often reveal more about the past and present. We

project our present fears and concerns into the narratives of the future in

order to distance ourselves from them, so that we may better understand them.

The narratives of the future are, by disubstantiation, very much the narratives

of the present.

|

|

|