|

(2017

midterm assignment) Model Student Midterm answers 2017 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Greg

Bellomy

10/15/2017

Future Narratives: Comparisons and Contrasts

In telling stories about an imagined future, authors generally confine

themselves to one or a combination of two or three different types, which

include apocalypse, evolution, and alternative narratives. Because readers can

interpret texts in divergent ways, it is possible that different readers can

attribute different intentions to the author, particularly regarding their

vision of a future. An examination of the narrative types is worthwhile in

enhancing discussion of authors’ future visions.

The apocalypse narrative usually tells the story of an ending, society,

government, culture or planet. Within the Western tradition, these narratives

are primarily found within the Bible, in the books of Daniel and Revelation.

These prophecies, although made by different people at different times, share

several things in common. Most importantly, both stories involve a vague

timeline, which seem to be intended to suggest that the prophecy could be

fulfilled at any day or minute. Another thing that is inherent to both narrative

styles is the use of phantasmagorical imagery; this mode of mixing aspects of

various animals and men calls to mind the mystical nature of a surrealistic

dream state. Like the mysterious time cycles associated with this genre, this

phantasmagorical style also allows for an expanded number of ways in which the

works can be interpreted and thus connected to the life of the reader. Another

aspect that defines apocalypse narratives is their attractiveness to readers; in

a world where people sense decay and decline (rather than progress), the

apocalypse narrative offers the hope of restoration, while promising destruction

to people or institutions that would otherwise prevent them (also to many

bystanders). In this way, apocalypse narratives seem very purposed towards the

building of fear and hope, much like the religions that spawned them. While

these types of narratives remain popular today, it is much more common to see

the transplantation of apocalypse elements into other narrative forms than the

repetition of the apocalypse as a narrative template.

One

good example of the infusion of apocalypse elements into a different narrative

form is in Parable of the Sower. The book’s protagonist, Lauren Olamina,

is a daughter to a Christian preacher. The walled-in community where she lives

is slowly declining into hardship, deprivation, and violence. As Lauren’s

community members watch the world outside their walls continue to crumble, they

turn to her father for spiritual guidance and counsel until his disappearance.

Although the book is set in some sort of economic and ecological apocalypse,

Parable resists this reading at some key points. First, Lauren has a genetic

mutation that allows her to sense the pain of beings within her line of sight.

Although this development is attributed to the use or abuse of pharmaceutical

drugs, this change holds high importance within the development of the story; it

necessitates finding new ways to solve problems and places a practical limit on

the way that violence can be exercised by the character. Along with this

mutation (which readers learn that Lauren is not the only one), there is the

motif in Lauren’s journals which repeats, “God is change.” When one considers

that the entire journey is about survival and starting a sustainable community

called “Acorn,” along with the fact that most religiously inclined people have

an intention of behaving and living in a “God-like” manner, Parable is better

understood as being an evolutionary narrative.

Unlike the revealed information of the apocalypse narratives (from some divine

or mystical source), the evolutionary narrative is based upon the observation of

change over time. In Parable, Lauren’s writings about the rules and beliefs of

Earthseed are based upon her observations of what and does not work for the

purposes of survival. Likewise, the problems that Lauren and her cohorts face

seem to be based on the imagination of current problems (in Butler’s 1992) into

the future, including corporatization, drug epidemics, and environmental

disasters. HG Wells’ book The Time Machine, also builds its vision in this way.

Going hundreds of thousands of years into the future, Wells imagines the class

and social divide (partially inspired by the Industrial Revolution) forward into

the division between two biologically different species of humanoids: the gentle

Eloi are the incarnation of the upper class, and the disgusting Morlocks embody

his future vision of the proletariat. Although both

Parable and

Time Machine have their own problems

in terms of plot, the authors seem to agree about the question of what

constitutes progress. The same question is explored in “Better Be Ready Half

Past Eight,” which is set in a near-future scenario, where the protagonist deals

with his friend changing gender and sex. Once he comes to terms with this

change, the hero ends up unsure about his son’s future gender status and even

his own. Despite the uncharacteristically short timeline of this type,

Half Past Eight also illustrates the

way that changing ideas and bodies affect one another. Butler illustrates this

by showing how failing institutions and social practices dictate the development

of new mores and traits for a viable future; Wells also shows the same concept,

particularly in the evolution of the Morlocks to survive in subterranean

conditions. He also demonstrates this even more in the description of

technologies and knowledge that are gained and lost. This differs from the

tendency in apocalypse narratives of labeling things as good and evil; from the

objective viewpoint in the evolutionary narrative, these distinctions are both

impossible and unreasonable to make. The short story,” Somebody Up There Likes

Me,” also demonstrates the concept of confusion regarding quality, but more in

terms of communication. The “high signal to noise ratio” attributed to humanity

and nonsensical correspondence with a distant wife create the pervasive feeling

of anomie in the story. Because our subjective human nature generally compels us

to qualify things relative terms, a third future narrative form has been

created: the alternative narrative.

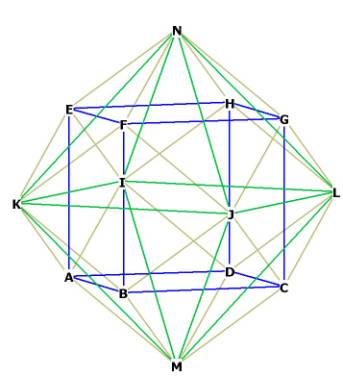

Alternative narratives of the future give authors the ability to apply their

subjective judgements to a continuum of infinite possibilities and

probabilities. In Garden of Forking Paths, the main character assassinates an

Englishman because they are enemies at one point of the branching timeline in

the future. Although this may seem abhorrent from a reader’s perspective, Borges

demonstrates the ambiguous nature of understanding an act from a perspective in

time. The same can be said of “Mozart in the Mirrorshades;” in this short story,

the denizens of one future timeline travel back into other, alternative,

timelines, to bring back oil and mineral resources. This, of course, has

disastrous effects on the worlds which they visit, but provides much needed

resources for the home world. Ironically, the denizens of the past world still

manage to distract and divide the occupiers enough so that eventually they are

forced to leave (and some time-natives manage to escape with the occupiers). In

this story, the things that were good for some in one time, are bad for another

in a different time; but, some of these same things are also the opposite for

other people. These two tales illustrate the relativistic notion within

alternative timelines, which differs from the moral and amoral perspectives of

apocalypse and evolutionary narratives. The alternative future vision, which is

not constrained by the revelation of divine wisdom or eons of unimaginable time,

gives authors the freedom to explore ideas in ways that does not quite make

temporal or spatial sense (much like quantum theory). In this sense, the

emergence of the alternative narrative seems to mirror the changing ways in

which we perceive the world.

Being

forever trapped in the present, writers will continue to provide their future

narratives, so long that writing is a part of our culture. For now, the future

of future visions is in the alternative narrative form. Apocalyptic and

evolutionary narratives will undoubtedly be borrowed from for the foreseeable

future; but, their rigidity with regards to timelines and their processes of

development will most likely limit them to being elements in an alternative

future story. Conversely, the alternative future vision allows the perfect

vehicle through which writers can suspend (or alter) the forces of God or nature

into a vision that suits their artistic intent. Likewise, the alternative

timeline represents the fringes of our comprehension, whereas the other two

styles are reliant upon what is “known,” either from God or observation.

|

|

|