|

(2016

midterm assignment) Model Student Midterm answers 2016 (Index) Essay 1: Compare, contrast, and evaluate Narratives of the Future |

|

Christa Van Allen

Telling Tales of Tomorrow

Literature of the Future is one of the strangest but most engaging classes I

have ever had the pleasure to participate in, and the primary narratives lend

themselves to that excitement. So far we have had extensive discussions on

Creation/Apocalypse, Evolution Narratives, and Alternative Future storylines.

Time has always fascinated humankind and so, along with fantasy, time-theorizing

stories continue to grow in popularity. I think that this may be due to the

natural allure of the unknown.

Of

the narratives discussed I find myself less assured in the Creation/Apocalypse

genre. This stays primarily in biblical texts, and though straight forward, also

cycles on itself. It is a narrative with a clear beginning and end, but a not so

simple middle. The linear pattern is understandable and expectant because of the

comparatively short scale, roughly 6,000 to 10,000 years, but the overarching

ether and old English writing has caused me to stumble over interpretations.

Ironically because the story of Adam and Eve is so simple, I feel like we’re not

being told the whole story, and I’m left with questions. It is perhaps put best

within Jesus’ words during the ‘Little Apocalypse’,

“Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my

words shall not pass away”. Words need not change to have their meanings

transform.

In

Parable of the Sower, Lauren goes on

her own version of the creation/apocalypse narrative, but with a far more

circular view. In her case, the story starts with the last cycle’s apocalypse

and follows her through to the new start of creation. She is one of the few

survivors of a world engulfed by danger, fire, and death, and she is the direct

mother to the new beginning of growth and change. Lauren’s thoughts on her

religion in chapter 24 best summarize this idea.

"God is Change, and in the end, God does

prevail. But we have something to say about the whens and the whys of that end."

She seems to imply that while God may be the ultimate decider of whether or not

things continue, humanity’s influence is what keeps the wheels in motion, both

in terms of the start and the end.

Evolution builds on the past to predict the future. I believe that despite its

necessity for a longer time scale up in the billions of years, evolution

narratives devote more time to slow progression and explanation, complex enough

that questions are answered immediately or through patience. All events are tied

together in an ever-growing spiral of time, even if some pieces still need to be

uncovered. Because it relies on a theory of change, narratives that follow this

way of storytelling can acknowledge possible theories and transformations or

even admit when they are wrong. The dog-eat-dog, and adaptable ideology of

Darwin are well-known in modern society, so it is fairly reasonable to presume

their continued use in future narratives of various genres. One can even argue,

that the bible itself incorporates some ideals of evolution, as Melissa

Holesovsky, mentioned in her 2015 midterm submission,

“Though the book of Genesis begins with

the inspiring story of creation, the expulsion of Adam and Eve resulting in

their “rebirth” as worldly beings is both apocalyptic and evolutionary”.

When

we read the story Bears Discover Fire,

I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. It may have been due to its surprisingly

nonchalant delivery of the story, but when I think about now, such an event

would probably be met with the same sort of cautious observation and theorizing

displayed in the text. The book follows an evolutionary event as humanity might

if given the opportunity to view it in a somewhat faster timeframe. The bears

discovering fire is the big thing, but because of their finding it, they have

also ceased hibernating and moved closer to, if not in direct contact with,

people. These are side-effects of the event, and though theories are considered

as to why they happened, there are no similar quandaries as to how the bears

learned to make fire in the first place. The questioning seems primarily on what

the bears are doing currently and what it may lead to. Working forwards before

looking back, I suppose. It’s an interesting take on the evolution narrative,

explaining both how this discovery is changing the bears and then how humanity’s

discovery of the bear’s discovery changes human actions and behavior.

Evolutionary on two different fronts.

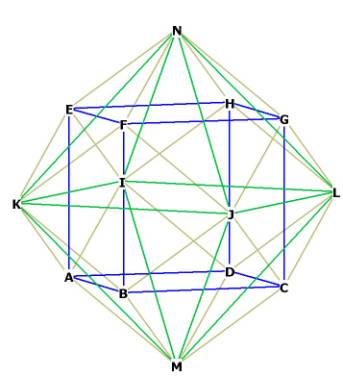

Alternative future narratives are the wildcards of the group. They can

effectively be part of or apart from both of the previous narratives. They

dabble into quantum physics, theoretical timelines, and alternate dimensions

with no real proper evidence to suggest one direction or another. They model

best like a tree where at one point a decision must be made, and regardless of

your choice, either resulting branch is considered to be a legitimate existing

future, forever expanding and growing outward as more and more choices or events

occur. Time in these stories is mixed, one universe may be older or younger than

your own, may be influenced by yours or entirely oblivious, and they are

unstable, forever shifting, and entirely unpredictable. It is such a wide and

overwhelming interpretation of theoretical science that the implied

possibilities are mind boggling.

As

specific examples go, The Time Machine

by H.G. Wells was particularly interesting, and this is because the very

creation of a time machine lets you play with dimensions. Early on is a line

about how “…Time is only a kind of

Space.” There exists in the narrative, observations on what the time

traveler saw, but also questions about how these things developed. You could

even ask if the development of the time machine changed the future into what the

traveler saw. Mozart in Mirrorshades

also embraces this narrative, not

only warping America’s and the world’s history, but admitting that the world

that we spend time in for the story’s duration is nowhere near the only one that

our prime characters have visited or created. In fact, it could be argued that

every story we cover in our class has the potential to be a true future scape.

We may get to see one or none of them because our version of the future either

does follow, comes close to, splits off from, or never follows, the specific

changes and pathways that lead to them. Spend too long contemplating that and

you could get a headache.

Most

often you hear that phrase of history and those that fail to learn from it being

forced to repeat it. It’s a valid piece of advice, but so is the simple standard

of being better safe than sorry. To ever be prepared for the future you must

consider what can happen and plan accordingly. Time has a way of changing

things, so it’s best to observe what is happening, predict what may come of it,

and roll with the punches if some previously unforeseen variable threw

everything you thought out the window. Future narratives are fun but, for the

moment, not really happening. However, the unknown that they explore is

fascinating and equalizing for all that pursue them. No one, student or teacher,

actually knows what the future will bring until it gets here, but in the

meantime we can all take solace in knowing that we are carefully mapping it out

together.

|

|

|