American Minority Literature

|

The Story of the Virgin of Guadalupe |

|

For additional photos and images associated with Guadalupe, scroll to bottom of page.

Instructor's notes:

- Numerous written and spoken versions of the Guadalupe narrative

are multiplied by various translations and re-tellings. Details were modified for Old and New World audiences.

New versions are freely rendered in various media

even now. No single text is accepted to the exclusion of others. It remains a living story.

- The present text is translated from an account first published in Nahuatl

(the language of the Aztecs) by Luis Lasso de la Vega in 1649. That version is based on a

copy by the Indian scholar Antonio Valeriano from the original Nican Mopohua, or

Huei Tlamahuitzoltica, which is not extant.

- The website Our Lady of Guadalupe, Patroness of the Americas (http://www.sancta.org/nican.html,

28 Oct. 2008) provides the basis for this unattributed English translation,

which is copied and adapted with gratitude. The present version is

provided only as a teaching text and does not pretend to scholarly

authority.

- Some passages are edited for spelling and clarity. No

meanings are substantially altered. Bolded highlights and bracketed comments are

by the instructor. Passages in red are speech attributed to the Virgin

Mary, a printing technique called a rubric.

- Names and terms marked with an asterisk (*) are indexed at the bottom of this webpage.

Purposes of this text for American Minority Literature:

- The Lady of Guadalupe may be read as Mexico's

"creation story" because of its fusion of European-Catholic and

Indian-traditional elements--similar to the mestizo identity of mixed

European and Indian genealogies.

- These complementary

modern and traditional identities

may match Objective 4 + Objective 5c on Mexican Americans as "The Ambivalent

Minority."

Risks & resolutions of reading a vital religious text in a public institutions:

- Catholic or Hispanic believers may be sensitive to

literary-cultural treatment of sacred texts and symbols.

- Secularists may resist introducing any vital religious text in a public institution because it

may violate separation of church and state and promote irrational

thought or social division.

- Members of other religious traditions may demand

equal time and attention.

- These objections won't go away, but literary and cultural studies treat the Virgin of Guadalupe text neutrally as a story or narrative. (Objective 6b: literary devices such as narrative and figures of speech.) [Add symbols, a crucial meeting ground between literature and religion.]

Other points of interest:

- The Virgin of Guadalupe is an essential cultural

symbol for Mexican America. As a symbol, Guadalupe can signify diverse

meanings to diverse audiences.

- Historical currency: In 2002 in Mexico City, Pope John Paul II canonized Juan Diego as a saint of the Catholic Church: article.

The Story of the Virgin of Guadalupe

Ten years after the seizure of the city of Mexico [the conquest by Cortez], war came to an end and there was peace amongst the people; in this manner faith started to bud, the understanding of the true God, for whom we live. At that time, in the year fifteen hundred and thirty one, in the early days of the month of December, it happened that there lived a poor Indian, named Juan Diego, said being a native of Cuautitlan. Of all things spiritually he belonged to Tlatilolco.

| FIRST APPARITION |

|---|

On a Saturday just before dawn, he was on his way to

pursue divine worship and to engage in his own errands. As he reached the base

of the hill known as Tepeyac*, came the break of day, and he heard singing atop

the hill, resembling singing of varied beautiful birds.

Occasionally the voices of the songsters would cease, and it appeared as if the

mount responded. The song, very mellow and delightful, excelled that of the

coyoltototl* and the tzinizcan* and of other pretty singing birds. Juan Diego

stopped to look and said to himself: “By fortune, am I worthy of what I hear?

Maybe I dream? Am I awakening? Where am I? Perhaps I am now in the terrestrial

paradise which our elders had told us about? Perhaps I am now in heaven?” He was

looking toward the east, on top of the mound, from whence came the precious

celestial chant; and then it suddenly ceased and there was silence. He then

heard a voice from above the mount saying to him: “Juanito, Juan Dieguito.” Then

he ventured and went to where he was called. He was not frightened in the least;

on the contrary, overjoyed. [May "elders" above refer to

either church elders

or traditional Indian elders?]

Then he climbed the hill, to see from were he was being called. When he reached

the summit, he saw a Lady, who was standing there and told him to come hither.

Approaching her presence, he marveled greatly at her superhuman grandeur; her

garments were shining like the sun; the cliff where she rested her feet, pierced

with glitter, resembling an anklet of precious stones, and the earth sparkled

like the rainbow. The mezquites, nopales, and other different weeds, which grow

there, appeared like emeralds, their foliage like turquoise, and their branches

and thorns glistened like gold. He bowed before her and heard her word, tender

and courteous, like someone who charms and esteems you highly.

She said: “Juanito, the most humble of my sons, where are you going?” He replied: “My Lady, I have to reach your church in Mexico, Tlatilolco*, to pursue things divine, taught and given to us by our priests, delegates of Our Lord.”

She then spoke to him: “Know and understand well, you the most humble of my son, that I am the ever virgin Holy Mary, Mother of the True God for whom we live, of the Creator of all things, Lord of heaven and the earth.

"I wish that a temple be erected here quickly, so I may therein exhibit and give all my love, compassion, help, and protection, because I am your merciful mother, to you, and to all the inhabitants on this land and all the rest who love me, invoke and confide in me; listen there to their lamentations, and remedy all their miseries, afflictions and sorrows.

"And to accomplish what my clemency pretends, go to the palace of the bishop of Mexico, and you will say to him that I manifest my great desire, that here on this plain a temple be built to me; you will accurately relate all you have seen and admired, and what you have heard. Be assured that I will be most grateful and will reward you, because I will make you happy and worthy of recompense for the effort and fatigue in what you will obtain of what I have entrusted. Behold, you have heard my mandate, my humble son; go and put forth all your effort.”

At this point he bowed before her and said: “My Lady, I am going to comply with your mandate; now I must part from you, I, your humble servant.” Then he descended to go to comply with the errand, and went by the avenue which runs directly into Mexico City.

| SECOND APPARITION |

|---|

Having entered the city, and without delay, he went straight to the bishop’s palace, who was the recently arrived prelate* named Father Juan de Zumarraga, a Franciscan religious. On arrival, he endeavored to see him; he pleaded with the servants to announce him; and after a long wait, he was called and advised that the bishop had ordered his admission.

As he entered, he bowed, and on bended knees before him, he then delivered the message from the lady from heaven; he also told him all he had admired, seen, and heard. After having heard him speak his vision and message, it appeared incredible. Then he told him: “You will return, my son, and I will hear you at my pleasure. I will review it from the beginning and will give thought to the wishes and desires for which you have come.” He left and he seemed sad, because his message had not been realized in any of its forms.

He returned on the same day. He came directly to the top of the hill, met the Lady from heaven, who was awaiting him, in the same spot where he saw her the first time.

Seeing her, he prostrated before her and said: “Lady, I went where you sent me to comply with your command. With difficulty I entered the prelate’s study. I saw him and expressed your message, just as you instructed me. He received me benevolently and listened attentively, but when he replied, it appeared that he did not believe me. He said: 'You will return; I will hear you at my pleasure. I will review from the beginning the wish and desire which you have brought.'

"I perfectly

understood by the manner he replied that he believes it to be an invention of

mine that you wish that a temple be built here to you, and that it is not your

order; for which I exceedingly beg, Lady and my Child, that you entrust the

delivery of your message to someone of importance, well known, respected, and

esteemed, so that they may believe in him; because I am a nobody, I am a small

rope, a tiny ladder, the tail end, a leaf, and you, my Lady, you send me to a place where I never visit nor repose. Please

excuse the great unpleasantness and let not fretfulness befall, my Lady and my

All.”

The Blessed Virgin answered: “Hark, my son the least, you

must understand that I have many servants and messengers, to whom I must entrust

the delivery of my message, and carry my wish, but it is of precise detail that

you yourself solicit and assist and that through your mediation my wish be

complied. I earnestly implore, my son the least, and with sternness I command

that you again go tomorrow and see the bishop. You go in my name, and make known

my wish in its entirety that he has to start the erection of a temple which I

ask of him. And again tell him that I, in person, the ever-virgin Holy Mary,

Mother of God, sent you.”

Juan Diego replied: “Lady, let me not cause you affliction. Gladly and willingly I will go to comply your mandate. Under no condition will I fail to do it, for not even the way is distressing. I will go to do your wish, but perhaps I will not be heard with liking, or if I am heard I might not be believed. Tomorrow afternoon, at sunset, I will come to bring you the result of your message with the prelate’s reply. I now take leave, my Lady. Rest in the meantime.” He then left to rest in his home.

| THIRD APPARITION |

|---|

The next day, Sunday, before dawn, he left home on his way to Tlatilolco, to be instructed in things divine, and to be present for roll call, following which he had to see the prelate. Nearly at ten, and swiftly, after hearing Mass and being counted and the crowd had dispersed, he went. On the hour Juan Diego left for the palace of the bishop. Hardly had he arrived, he eagerly tried to see him.

Again with much difficulty he was able to see him. He kneeled before his feet. He saddened and cried as he expounded the mandate of the Lady from heaven, which God grant he would believe his message, and the wish of the Immaculate Virgin, to erect her temple where she willed it to be. The bishop, to assure himself, asked many things, where he had seen her and how she looked; and Juan described everything perfectly to the bishop.

Notwithstanding his precise explanation of her appearance and all he had seen and admired, which in itself reflected her as being the ever-virgin Holy Mother of the Savior, Our Lord Jesus Christ, nevertheless the bishop did not give credence and said that he could not do what Juan had asked based only on his request. In addition, a sign was necessary, so that he could be believed that he was sent by the true Lady from heaven. In reply, Juan Diego said to the bishop: “My lord, what must be the sign you request? I will go to ask the Lady from heaven who sent me here.”

The bishop, seeing that Juan ratified everything without doubt and was not retracting anything, dismissed Juan Diego. Immediately the bishop ordered some persons of his household, whom he could trust, to go and watch where Juan Diego went and whom he saw and to whom he spoke. So it was done. Juan Diego went straight to the avenue.

Those who followed him, as they crossed the ravine, near the bridge to Tepeyacac, lost sight of him. They searched everywhere, but he could not be seen. Thus they returned, not only because they were disgusted, but also because they were hindered in their intent, causing them anger. And that is what they informed the bishop, influencing him not to believe Juan Diego; they told him that he was being deceived; that Juan Diego was only forging what he was saying, or that he was simply dreaming what he said and asked. They finally schemed that if he ever returned, they would hold and punish him harshly, so that he would never lie or deceive again. [Objective 2c. "Quick check" on minority status: What is the individual’s or group’s relation to the law or other dominant institutions? Does "the law" (e. g., the police) make things better or worse?]

In the meantime, Juan Diego was with the Blessed Virgin, relating the answer he was bringing from his lordship, the bishop. The lady, having heard, told him: “Well and good, my dear. Return here tomorrow, so you may take to the bishop the sign he has requested. With this he will believe you, and in this regard he will not doubt you nor will he be suspicious of you; and know, my dear, that I will reward your solicitude and effort and fatigue spent on my behalf. Lo! go now. I will await you here tomorrow.”

| FOURTH APPARITION |

|---|

On the following day, Monday, when Juan Diego was to carry a sign so he could be believed, he failed to return, because, when he reached his home, his uncle, named Juan Bernardino, had become sick, and was gravely ill. First he summoned a doctor who aided him; but it was too late, he was gravely ill. By nightfall, his uncle requested that by break of day he go to Tlatilolco and summon a priest, to prepare him and hear his confession, because he was certain it was time for him to die, and that he would not arise or get well.

On Tuesday, before dawn, Juan Diego came from his home to Tlatilolco to summon a priest; and as he approached the road which joins the slope to Tepeyacac hilltop, toward the west, where he was accustomed to cross, said: “If I proceed forward, the Lady is bound to see me, and I may be detained, so I may take the sign to the prelate, as prearranged; that our first affliction must let us go hurriedly to call a priest, as my poor uncle certainly awaits him.” Then he rounded the hill, going around, so he could not be seen by her who sees well everywhere. He saw her descend from the top of the hill and was looking toward where they previously met.

She approached him at the side of the hill and said to him: “What’s there, my son? Where are you going?” Was he grieved, or ashamed, or scared? He bowed before her. He saluted, saying: “Lady, God grant you are content. How are you this morning? Is your health good, Lady? I am going to cause you grief. Know that a servant of yours is very sick, my uncle. He has contracted the plague, and is near death. I am hurrying to your house in Mexico to call one of your priests, beloved by our Lord, to hear his confession and absolve him, because, since we were born, we came to guard the work of our death. But if I go, I shall return here soon, so I may go to deliver your message. Lady and my Child, forgive me, be patient with me for the time being. I will not deceive you. Tomorrow I will come in all haste.”

[Instructor's comment: This episode may mark

an aspect of Objective 5c on Mexican Americans as "the ambivalent minority":

Juan Diego is torn between his unexpected mission as a messenger for a divine

figure and his traditional duty to his family.]

After hearing Juan Diego speak, the Most Holy Virgin answered:

“Hear me and understand well, my son the least, that

nothing should frighten or grieve you. Let not your heart be disturbed. Do not

fear that sickness, nor any other sickness or anguish. Am I not here, who is

your Mother? Are you not under my protection? Am I not your health? Are you not

happily within my fold? What else do you wish? Do not grieve nor be disturbed by

anything. Do not be afflicted by the illness of your uncle, who will not die now

of it. be assured that he is now cured.” (And then his uncle was cured,

as it was later learned.)

When Juan Diego heard these words from the Lady from heaven, he was greatly consoled. He was happy. He begged to be excused to be off to see the bishop, to take him the sign or proof, so that he might be believed. The Lady from heaven ordered to climb to the top of the hill, where they previously met. She told him: “Climb, my son the least, to the top of the hill; there where you saw me and I gave you orders, you will find different flowers. Cut them, gather them, assemble them, then come and bring them before my presence.”

Immediately Juan Diego climbed the hill, and as he reached the summit, he was amazed that so many varieties of exquisite rosas de Castilla* were blooming, long before the time when they are to bud, because, being out of season, they would freeze. They were very fragrant and covered with dewdrops of the night, which resembled precious pearls. Immediately he started cutting them. He gathered them all and placed them in his tilma*. The hilltop was no place for any kind of flowers to grow, because it had many crags, thistles, thorns, nopales and mezquites. Occasionally weeds would grow, but it was then the month of December, in which all vegetation is destroyed by freezing.

He immediately went down the hill and brought the different roses which he had cut to the Lady from heaven, who, as she saw them, took them with her hand and again placed them back in the tilma, saying: “My son, this diversity of roses is the proof and the sign which you will take to the bishop. You will tell him in my name that he will see in them my wish and that he will have to comply to it. You are my ambassador, most worthy of all confidence. Rigorously I command you that only before the presence of the bishop will you unfold your mantle and disclose what you are carrying. You will relate all and well; you will tell that I ordered you to climb to the hilltop, to go and cut flowers; and all that you saw and admired, so you can induce the prelate to give his support, with the aim that a temple be built and erected as I have asked.”

After the Lady from heaven had given her advice, he was on his way by the avenue that goes directly to Mexico; being happy and assured of success, carrying with great care what he bore in his tilma*, being careful; that nothing would slip from his hands, and enjoying the fragrance of the variety of the beautiful flowers.

| THE MIRACLE OF THE IMAGE |

|---|

When he reached the bishop’s palace, there came to meet

him the majordomo and other servants of the prelate. He begged them to tell the

bishop that he wished to see him, but none were willing, pretending not to hear

him, probably because it was too early, or because they already knew him as

being of the troublesome type, because he was pestering them; and, moreover, they

had been advised by their co-workers that they had lost sight of him, when they

had followed him.

He waited a long time. When they saw that he had been there a long time,

standing, crestfallen, doing nothing, waiting to be called, and appearing like

he had something which he carried in his tilma, they came near him, to see what

he had and to satisfy themselves. Juan Diego, seeing that he could not hide what

he had, and on account of that he would be molested, pushed or mauled, uncovered

his tilma a little, and there were the flowers.

Upon seeing that all the different rosas de Castilla*, and out of season, the courtiers were thoroughly amazed, also because the flowers were so fresh and in full bloom, so fragrant and so beautiful. Three times they dared to seize and pull some out, but they were not successful. They were not lucky because when then tried to get them, they were unable to see real flowers. Instead, they appeared painted or stamped or sewn on the cloth. Then they went to tell the bishop what they had seen and that the Indian who had come so many times wished to see him, and that he had reason enough so long anxiously eager to see him.

Upon hearing this, the bishop realized that Juan Diego was carrying the proof, to confirm what the Indian requested. Immediately he ordered Juan Diego's admission. As he entered, Juan Diego knelt before him, as he was accustomed to do, and again related what he had seen and admired, also the message.

Juan Diego said: “Sir, I did what you ordered, to go forth and tell my Ama*, the

Lady from heaven, Holy Mary, precious Mother of God, that you asked for a sign

so that you might believe me that you should build a temple where she asked it

to be erected; also, I told her that I had given you my word that I would bring

some sign and proof, which you requested, of her wish. She condescended to your

request and graciously granted a sign and proof to complement

her wish. Early today she again sent me to see you; I asked for the sign so you

might believe me, as she had said that she would give it, and she complied. She

sent me to the top of the hill, where I was accustomed to see her, and to cut a

variety of rosas de Castilla. After I had cut them, I brought them, she took

them with her hand and placed them in my cloth, so that I bring them to you and

deliver them to you in person. Even though I knew that the hilltop was no place

where flowers would grow, because there are many crags, thistles, thorns,

nopales and mezquites, I still had my doubts. As I approached the top of the

hill, I saw that I was in paradise, where there was a great variety of exquisite rosas de Castilla, in brilliant dew, which I immediately cut. She had told me

that I should bring them to you, and so I do it, so that you may see in them the

sign which you asked of me and comply with her wish; also, to make clear the

veracity of my word and my message. Behold. Receive them.”

He unfolded his white cloth, where he had the flowers; and when they scattered

on the floor, all the different varieties of rosas de Castilla, suddenly there

appeared the drawing of the precious Image of the ever-virgin Holy Mary, Mother

of God, in the manner as she is today kept in the temple at Tepeyacac, which is

named Guadalupe.

[Some translations add: "Her sacred face is very beautiful, grave, and

somewhat dark . . . ."]

When the bishop saw the image, he and all who were present fell to their knees. Mary was greatly admired. They arose to see her; they shuddered and, with sorrow, they demonstrated that they contemplated her with their hearts and minds. The bishop, with sorrowful tears, prayed and begged forgiveness for not having attended her wish and request. When he rose to his feet, he untied from Juan Diego’s neck the cloth on which appeared the Image of the Lady from heaven. Then he took it to be placed in his chapel. Juan Diego remained one more day in the bishop’s house, at his request.

The following day he told him: "Well! show us where the Lady from heaven wished her temple be erected.” Immediately, he invited all those present to go.

| APPARITION TO JUAN BERNARDINO |

|---|

As Juan Diego pointed out the spot where the lady from heaven wanted her temple built, he begged to be excused. He wished to go home to see his uncle Juan Bernardino, who was gravely ill when he left him to go to Tlatilolco to summon a priest, to hear his confession and absolve him. The Lady from heaven had told him that he had been cured. But they did not let him go alone, and accompanied him to his home.

[Instructor's comment: Another episode of

Objective 5c on Mexican Americans as "the ambivalent minority": Juan Diego is

torn between his unexpected mission as a public messenger and his traditional

duty to his family.]

As they arrived, they saw that his uncle was very happy and nothing ailed him.

He was greatly amazed to see his nephew so accompanied and honored, asking the

reason of such honors conferred upon him. His nephew answered that when he went

to summon a priest to hear his confession and to absolve him, the Lady from

heaven appeared to him at Tepeyacac, telling him not to be afflicted, that his

uncle was well, for which he was greatly consoled, and she sent him to Mexico,

to see the bishop, to build her a house in Tepeyacac.

Then the uncle manifested that it was true that on that occasion he became well

and that he had seen her in the same manner as she had appeared to his nephew,

knowing through her that she had sent him to Mexico to see the bishop. Also, the

Lady told him that when he would go to see the bishop, to reveal to him what he

had seen and to explain the miraculous manner in which she had cured him, and

that she would properly be named, and known as the blessed Image, the

ever-virgin Holy Mary of Guadalupe.

Juan Bernardino was brought before the presence of the bishop to inform and

testify before him. Both he and his nephew were the guests of the bishop in his

home for some days, until the temple dedicated to the Queen of Tepeyacac was

erected where Juan Diego had seen her.

The bishop transferred the sacred Image of the lovely lady from heaven to the main church, taking her from his private chapel where it was, so that the people would see and admire her blessed Image. The entire city was aroused; they came to see and admire the devout Image, and to pray. They marveled at the fact that she appeared as she did and for her divine miracle, because no living person of this world had painted her precious Image.

Terms or names from Story of Lady of Guadalupe:

Ama =

coyoltototl = grackle?

prelate = a dignitary of a church, as a bishop

rosas de Castilla = Rose of Castile, among the most fragrant roses; originally known as the Damascus Rose (Syria); planted throughout the Roman Empire, brought to New World by missionaries; source of rose oil and attar of rose.

tilma or tilmatli = outer men's garment worn by Aztecs and other peoples of Central Mexico

Tlatilolco = former market district of Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan = the Aztec capital in current Mexico City

Tepeyac or Tepeyacac = hill north of Mexico City, site of the Basilica of Guadalupe

tzinizcan = a multi-colored, dove-like bird

Images and photos associated with Guadalupe

"Her sacred face is very beautiful, grave, and somewhat dark . . . ." The image of Guadalupe is a statement of Mestizo identity, in which Indian and European bloodlines and features are blended.

|

|

|

God the Father painting the image of Guadalupe

Juan Diego opening his tilma to spill the roses and show the

image

A popular scroll representing the story of Guadalupe

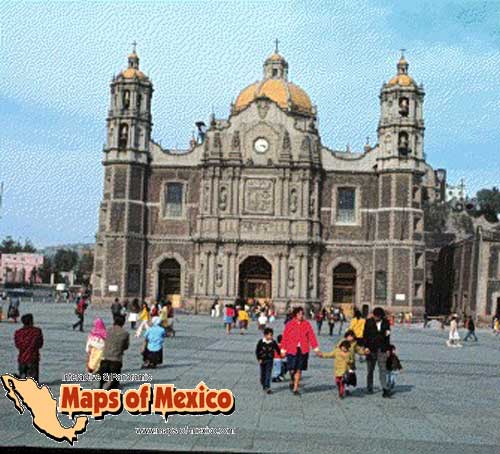

Basilica of Guadalupe on Tepeyac Hill north of Mexico City

New Cathedral, built 1974-76

Old Cathedral

begun 1531, completed 1709

Above & below: the painting in the basilica

Article on Canonization of Juan Diego

LITR

4332 American Minority Literature 2008 Syllabus

Course Objectives

-

Course Objectives are ideas and terms developed in lectures, discussions, presentations, and examinations.

-

Objectives also identify learning outcomes.

Cultural or Minority-Concept Objectives (1-4)

- Most minority or multicultural courses offer little theory or background on what makes a minority ethnic group.

- American Minority and Immigrant Literature define minority status in contrast to immigrant status:

Historical foundation:

-

The dominant culture of the USA is formed by

immigrants and their descendents

who live or imagine the American Dream.

-

Minorities are ethnic groups that do not fit

the immigrant narrative or profile,

for whom the American Dream has typically been an American Nightmare.

-

Our course traces how minority groups both express

and transcend this negative definition.

-

The ethnic groups that inarguably fit this minority definition are African Americans and American Indians.

-

Mexican Americans mix immigrant and minority aspects—more below.

Instructor's attitude: Americans want simple answers to complex problems so they can veg, party, and get rich or righteous. But the history and premises of minority culture differ so fundamentally from those of the American dominant / immigrant culture that simple answers are only denials of our complicated history. In light of such challenges, I've developed the following attitudes:

- Keep talking and listening. America's an unfinished story.

The answers are not written but being written.

- Question platitudes and discussion-stoppers like "All people are

basically just the same" and "Why can't we all just be Americans?"

- Sometimes the only positive outcome is not to be right but to act right.

Objective 1: Minority Definitions

American minorities are defined not by numbers but by power relations modeled on ethnic groups’ problematic relation to the American dominant culture.

1a. Involuntary participation and continuing oppression—the American Nightmare

Unlike the dominant immigrant culture, ethnic minorities did not choose to come to America or join its dominant culture. (African Americans were kidnapped, American Indians were invaded.)

Exploitation and oppression instead of opportunity—whereas immigrant cultures see America as a land of equality and opportunity, minorities may remember America as a place where their people have been dispossessed of property and power and deprived of basic human rights.

Thus the "social contract" of Native Americans and African Americans differs from that of European Americans, Asian Americans, and most Latin Americans.

The American dominant culture dismisses minority grievances: “That was a long time ago. . . . Get over it.” But consequences of "no choice" echo down the generations, particularly as minority difference versus assimilation (see objective 3).

1b. “Voiceless and choiceless”; “Voice = Choice”

Contrast the dominant culture’s self-determination or choice through self-expression or voice, as in "The Declaration of Independence."

1c. To observe alternative identities and literary strategies developed by minority cultures and writers to gain voice and choice:

-

“double language” (same words, different meanings to different audiences)

-

using the dominant culture’s words against them

-

conscience to dominant culture (which otherwise forgets the past).

1d. “The Color Code”

-

Literature represents the extremely sensitive subject of skin color infrequently or indirectly.

-

Western civilization transfers values associated with “light and dark”—e. g., good & evil, rational / irrational—to people of light or dark complexions, with huge implications for power, validity, sexuality, etc.

-

This course mostly treats minorities as a historical phenomenon, but the biological or visual aspect of human identity may be more immediate and direct than history. People most comfortably interact with others who look like themselves or their family.

-

Skin color matters, but how much varies by circumstances.

-

See also Objective 3 on racial hybridity.

1e. Dominant Culture Attitudes

-

Immigrants leave the past behind and think minorities should do the same.

-

Thus the dominant American immigrant culture dismisses minority grievances with shrugs, platitudes, and exasperation: “That was a long time ago. . . . Get over it”

-

Despite powerful evidence to the contrary, the dominant culture claims to be colorblind : “My parents raised me not to judge people by the color of their skin” (frequently articulated by those resentful of minority expression).

Objective 2: race > gender, class, etc.

To observe representations and narratives (images and stories) of ethnicity, gender, and class as a means of defining minority categories.

2a. Gender: Is the status of women, lesbians, and homosexuals analogous to that of ethnic minorities in terms of voice and choice? Do "women of color" become "double minorities?"

2b. To detect "class" as a repressed subject of American discourse.

-

“You can tell you’re an American if you can’t talk about class.”

-

American culture officially regards itself as "classless"; race and gender often replace class divisions of power, labor, ownership, or "place."

-

Class may remain identifiable in signs or “markers” of power and prestige

-

High-class status in the USA is often marked by plainness, simplicity, or lack of visibility.

2c. "Quick check" on minority status: What is the individual’s or group’s relation to the law or other dominant institutions? Does "the law" (e. g., the police) make things better or worse?

Objective 3: minority dilemma--assimilate or resist?

- Does the minority fight or join the dominant culture that exploited it?

- What balance do minorities strike between the economic benefits of assimilation and its personal or cultural sacrifices?

- In general, immigrants assimilate, while minorities remain separate (though connected in many ways).

3a. To contrast the dominant-culture ideology of racial separation from American practice, which frequently involves hybridity (mixing) and change.

-

The dominant American white culture typically sees races and genders as pure and permanent categories, perhaps allotted by God or Nature as a result of Creation, climate, natural selection, etc.,

-

But races always mix. What we call "pure" is only the latest change we're used to.

-

Racial divisions & definitions constantly change or adapt; e. g., the Old South's quadroons, octaroons, "a single drop"; recent revisions of racial origins of Native America; Hispanic as "non-racial" classification; "bi-racial"

-

Contrast “four races” (Aboriginal, Caucasian, Mongolian, & Negroid) with “only one race: the human race”

-

Instead of “black & white” dynamics, America is increasingly “brown” or "other"

-

“post-racial” identity of urban American youth following school integration, in contrast to "pure" races surviving in suburbs and private religious schools

3b. To identify the

"new American" who crosses, combines, or confuses ethnic or gender

identities

(e. g., Tiger Woods, Halle Berry, Lenny Kravitz, Mariah Carey, David Bowie, Boy

George, Tila Tequila Nicole Scherzinger of Pussycat Dolls, Vin Diesel)

Objective 4: individual & collective identities

To observe images of the individual, the family, and alternative families in the writings and experience of minority groups.

4a. Generally speaking, minority groups place more emphasis on “traditional” or “community” aspects of human society, such as extended families or alternative families, and they mistrust “institutions.” The dominant culture celebrates individuals and nuclear families and identifies more with dominant-cultural institutions or its representatives, like law enforcement officers, teachers, bureaucrats, etc. (Much variation, though.)

4b. To question sacred modern concepts like "individuality" and "rights" and politically correct ideas like minorities as "victims"; to explore emerging postmodern identities, e. g. “biracial,” “global,” and “post-national.”

Literary or Style Objectives (5 & 6)

Objective 5: Minority Narratives

-

“Narratives” are stories or plots, a sequence of events in which people act and speak in time.

-

Narratives concern not only how a writer tells a story, but also how an audience receives, processes, and makes meaning of it.

-

A cultural narrative is a collective story that unifies or directs a community--for example, The American Dream for the USA, or particular minority narratives that reflect an ethnic group's experience or range of expression.

-

Following Minority-Culture Objective 1, Minority Narratives differ from the dominant “American Dream” narrative—which involves voluntary participation, forgetting the past, and individuals or nuclear families.

-

Instead, minority narratives generally involve involuntary participation, reconnecting to a broken past, and traditional, extended, or alternative families.

Tabular summary of Objective 5:

contrasts

between the dominant culture's "American Dream" narrative and minority

narratives

|

Category of comparison / dominant or minority |

"American Dream" or immigrant narrative of dominant culture |

Minority Narratives (not traditional immigrants) |

|

Cultural group's original relation to USA |

Voluntary participation (individual or ancestor chose to come to America) |

Involuntary participation ("America" came to individual or ancestral culture) |

|

Cultural group's relation to time |

Modern or revolutionary: Forget the past, leave it behind, get over it (original act of immigration; future-oriented) |

Traditional but disrupted: Reconnect to the past (not voluntarily abandoned; more like a wound that needs healing) |

|

Social structures |

Abandonment of past context favors individual or nuclear family, erodes extended social structures. |

Traditional extended family shattered; non-nuclear, "alternative," or improvised families survive. |

5a. African American alternative narrative: “The Dream”

-

"The Dream" resembles but is not identical to "The American Dream."

-

Whereas the American Dream emphasizes immediate individual success, "the Dream" factors in setbacks, the need to rise again, and group dignity.

5b. Native American Indian alternative narrative: "Loss and Survival"

-

Dominant / immigrant culture leaves its past behind to gain rights and opportunities--the American Dream.

-

For Indians, the American Dream of immigration is the American Nightmare, creating an undeniable narrative of loss: the native people were once “the Americans” but lost most of their people, land, rights, and opportunities.

-

Despite these terrible losses, Native Americans defy the myth of "the vanishing Indian," choosing to "survive," sometimes in faith that the dominant culture will eventually destroy itself, and the forests and buffalo will return.

-

The American dominant culture usually writes only half of the Indians' story, romanticizing their loss (e. g., The Last of the Mohicans) and ignoring the Indians who adapt and survive.

5c. Mexican American narrative: “The Ambivalent Minority” or Third Way

-

"Ambivalent" means having "mixed feelings" or contradictory attitudes.

-

Mexican Americans as a group may feel or exemplify mixed feelings about whether they are a minority group that will remain separate or an immigrant culture that will assimilate.

-

As individuals or families who come to America for economic gain but suffer social dislocation, Mexican Americans resemble the dominant immigrant culture.

-

On the other hand, much of Mexico's historic experience with the USA resembles the experience of the Native Americans: much of the United States, including Texas, was once Mexico.

-

Does a Mexican who moves from Juarez to El Paso truly immigrate? In any case, it’s not just another immigrant story.

Objective 6: Minorities and Language

To study minority writers' and speakers' experiences with literacy & influence on literature and language.

6a. To regard literacy as the primary code of modern existence and a key or path to empowerment. (See obj. 3 on assimilation / resistance)

6b. To emphasize how all speakers and writers use literary devices such as narrative and figures of speech.

6c. To discover literature's power to express the minority voice and vicariously share minority experience.

6d. To assess minorities' status in the "canon" or curriculum of what is read and taught in schools

6e. To note variations of standard English by minority writers and speakers.

6f. To translate the "Dominant-Minority" relation to philosophical or syntactic categories of "Subject & Object," in which the "subject" is self-determining and active in terms of "voice and choice," while the "object" is acted upon, passive, or spoken for rather than acting and speaking.