|

LITR 4231 Early American

Literature Sample Research Posts 2014 (research post assignment) Research Post 2 |

|

Victoria Webb

Falsely Accused: Victims of the Salem Witch Trials

While doing research on the Salem Witch Trials and the main accusers, the

“afflicted girls,” I became interested in the people accused of witchcraft and

the motives behind the accusations. Through my research I learned that 78% of

the accused witches were women and the evidence used to support the claims of

witchcraft against them included unruly conduct and unladylike behavior (Reis).

Other absurd testimonies of the accusers included claiming to have seen the

“witches” sign the Devil’s book and witnessing their apparitions appear to them

and cause bodily harm to the accused (Reis). With these allegations, there were

a great number of victims that the village deemed fit for the role of “witch.” In

my research, I found there were some stories behind these victims that were

peculiar; I chose a few victims in particular to do further research on. While

they are only a few amongst the many that were accused and executed, their

stories were interesting enough to gain a substantial amount of recognition and

research.

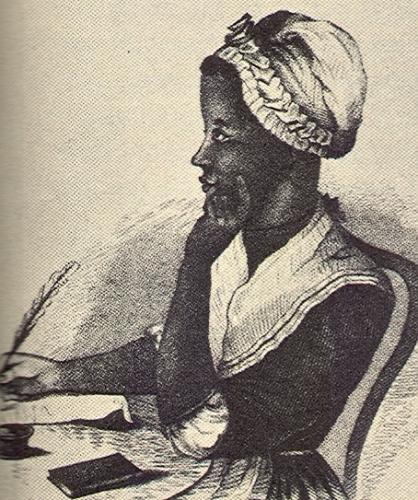

One of the first to be accused of witchcraft was the Parrises' slave Tituba. What

is interesting about her case was that she confessed to signing the Devil’s

book, flying in the air on a pole, and harming the afflicted girls (“Salem Witch

Trials: Tituba”). She did not confess to teaching the girls witchcraft or

fortune telling; this was a speculation that was brought on by the girls’

accusation. Her confession was due to the pressure and abuse from the Parrises;

this admission of guilt was the spark that ignited the witch-hunt. Since Tituba

was a slave, there is little information about her prior to the witch trials,

though researchers believe that she may have come from Barbados and was

purchased by Rev. Samuel Parris (Rosenthal). There is no official record of her

being married to John Indian, but it was inferred that the two were married or

at least lived together in that way. The significance of her marital status was

due to the cultural differences between Tituba and the Puritan village. Tituba

was an outsider in the village regardless of the witchcraft accusations; this

made her an easy scapegoat, especially for the afflicted girls when explaining

how they learned the fortune-telling technique which supposedly caused their

erratic behavior. Tituba later recanted her statement, but her forced confession

was the beginning of the end for other outsiders in Salem Village.

After Tituba, one of the first villagers to be accused and executed was Sarah

Good. Tituba named Sarah as a witch. She was most likely forced to do so by Rev.

Samuel Parris in order to rid Salem of Good. I

found Good’s story to be interesting because not only her, but her four-year-old

daughter Dorcas was imprisoned along with her. I see Sarah’s story as quite

tragic; she is an outsider in her village and woman who was down on her luck.

After the passing of her first husband, Good carried the debts from the

marriage; she and her second husband, William Good, were forced to beg for

charity and sometimes shelter in the village after much of their assets were

seized (“Sarah Good”). She was reported to have been a friendless person, and

had a tendency to scold and curse at other villagers who were not as giving to

her as she liked. No one in the village was particularly surprised when she was

accused; she fit the profile of “witch” according to witnesses and accusers. Her

daughter’s confession and allegation of her mother signing the Devil’s book was

just part of Good’s undoing (“Sarah Good”). In reality, Good was condemned the

moment she was accused and arrested; there would be no one to argue against the

allegations against Sarah. Even William Good did nothing to help his wife; in

fact, he had made statements against her character. While he did not exactly

declare her a witch, he did cause more harm for her by putting the public

against her even more than they already were. This made her execution much more

justified to the accusers. What I found to be the most interesting part of her

trial and execution were her last words to Rev. Noyes. She told him, “I am no

more a witch than you are a wizard. If you take away my life God will give you

blood to drink.” Twenty five years later Noyes suffered a hemorrhage and died

choking on his own blood (“Victims”).

One of the most tragic and suspicious cases was the trial and execution of

Rebecca Nurse. Nurse was a 71 year old mother of 8 with a notably good

reputation in the town. She was accused by the Putnam’s, including Ann who was

one of original afflicted girls. The Putnam’s had a known dispute with Rebecca

Nurse and her husband. In fact, all of Nurse’s accusers were either a part of

the Putnam family or close friends to the family (“The Trial of Rebecca Nurse”).

During her trial, a petition went around asking to rid Nurse of the charges

against her, and was signed by many respectable members of the village (“Rebecca

Nurse”). The original verdict from the trial was “not guilty”; however, after the

spectators and afflicted girls cried in outrage, the magistrates were asked to

reconsider the verdict. There were doubts about the accusations against Nurse

because of her age and moral behavior, but the reconsideration of the original

verdict was allowed (“Rebecca Nurse”). The second verdict came out just as the

accusers wanted: “guilty”. Nurse was sentenced to death on June 30th

and was executed on July 19th. Her death caused a public outrage

because of her “good Christian behavior,” according to those who were on her

side. Following her death, her two sisters were also accused and one was hung

just like Rebecca. Rebecca Nurse

was clearly the target of an ongoing feud between her family and the Putnams.

These three women are examples of the injustice that took place in Salem

during the witch-hunt and trials. The accusations made by the accusers were

completely absurd and all in all suspicious. There is no doubt that the victims

were targets of more than just witchcraft; the accused were the unwanted members

of the village, whether it was because they were outsiders or simply unlucky

enough to be disliked by an accuser. After the accusation of some unlikely

“witches,” such as Rebecca Nurse, it was obvious no one was safe from being

called a “witch”.

Works Cited

"Rebecca Nurse." Rebecca Nurse. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

<http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/SAL_BNUR.HTM>.

Reis, Elizabeth. Some Facts About The

Salem Witch Trials. N.p.,n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

<http://www.upa.pdx.edu/IMS/currentprojects/TAHv3/TAH_Course/2011_Materials/Salem_Trials_Fact_Sheet.pdf>

Rosenthal, Bernard. Tituba. OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 17, No. 4,

Witchcraft (Jul., 2003),

pp. 48-50. Organization of American Historians. n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2014. <

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163623>

"Sarah Good." Sarah Good. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

<http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/SAL_BGOO.HTM>.

"Salem Witch Trials: Tituba." Salem Witch Trials: Tituba. N.p., n.d. Web.

19 Apr. 2014.

<http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/people/tituba.html>.

"The Trial of Rebecca Nurse." History of Massachusetts. N.p., n.d. Web.

18 Apr. 2014. <http://historyofmassachusetts.org/the-trial-of-rebecca-nurse/>.

"Victims." Salem Witch Trials. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

<http://www.salemfocus.com/>.

|

|

|

|