|

LITR 4231 Early American

Literature Sample Research Posts 2014 (research post assignment) Research Post 2 |

|

Laura Tompkins

April 20, 2014

Phillis Wheatley: A Brief Discussion of Double Consciousness

On Being Brought from Africa to America

by Phillis Wheatley

'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic die."

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

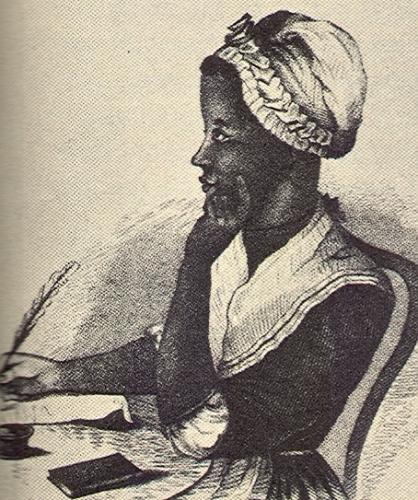

These eight lines seem deceptively simple and straightforward but upon

closer inspection, there is a wealth of information that can be read into them.

A brief background on Phillis Wheatley will help put the following thoughts into

perspective. Wheatley (1753-1784) was a slave, captured from West Africa when

she was about seven. Her name was a combination of the ship name, Phillis, and

the family who purchased her, Wheatley. The Wheatley family found that she was

very bright and they taught young Phillis to read and write. By the time she was

eighteen, she was able to have a collection of poems published, thanks to Mrs.

Wheatley and the Countess of Huntingdon. Although the family did not release

Wheatley until 1774, they provided a sanctuary for her, which allowed her to

continue to write. After Mrs. Wheatley passed away, Phillis Wheatley’s health

problems and poor marriage led to her early death. 1

The lives of slaves were wrought with double meanings. Lemert discusses

the idea of double-consciousness as

W.E.B. Du Bois defines it, “this sense of always looking at one’s self through

the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on

in amused contempt and pity” (127). Africans brought to the colonies were forced

into a position of not quite being African and not being American. This was a

difficult way for any Black person to live but especially someone as highly

educated as Wheatley. After the death of

Mrs. Wheatley, Phillis Wheatley had been advised of the possibility of going

back to Africa. She responded by saying that she had assimilated to her new

country and “for Wheatley, shared language implies a shared culture” (Watson

104). She did not speak the language of her African heritage, so this advice was

frustrating for her.

Another way that slaves lived with double meanings was through religion.

O’Neale examines the relationship between Wheatley’s poems and the spirituals

that were sung on the plantations. To an outsider it would seem as if slaves

were singing songs of worship but they also represented their protestations at

slavery (O’Neale 145). In “On Being Brought from Africa to America”, O’Neale

also points out that for the slaves, the idea that “He was not just ‘a God’ but

‘a Saviour’ (148) again gives more

meaning than what appears on the surface. Black Christians believed that their

prayers to God would be answered and they would be delivered just as the Jews

were in the Old Testament.

Bilbro argues for the view that Wheatley perhaps saw the slave trade as

God’s providence, if one reads the poem in a straightforward way, but also

reading them in context with some of her other early poems, including her elegy

for George Whitefield. She talks about redemption for all, regardless of status

but especially for those who were directly involved in the slave trade. Bilbro

also says that, “while it has been often criticized, this poem provides a

complex rhetorical answer to Cowper’s question about how God might bring some

good from the evil slave trade” (565). While this view may not sit comfortably

for many, it is a possibility that she felt that despite the evil of those

involved in the trade, they were just as much in need of a Savior and deserving

of redemption if they repented.

As with all great works of art, literature, and music, analyzing the

layers of meaning is always an important and lively conversation to have.

Discussing Wheatley’s writings is a good example of why understanding the

context of when it was written and knowing about her background is crucial to

the study of slave narratives.

Works Cited

Bilbro, Jeffrey1. "Who Are Lost And How They're Found: Redemption And Theodicy

In Wheatley, Newton, And Cowper." Early American Literature 47.3 (2012):

561-

589. Humanities Source. Web. 20 Apr. 2014.

Lemert, Charles C. Thinking the Unthinkable: The Riddles of Classical Social

Theories. Boulder: Paradigm, 2007. Print.

O'Neale, Sondra. "A Slave's Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley's Use Of Biblical Myth

And Symbol." Early American

Literature 21.(1986): 144-165. Humanities

Source. Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

Watson, Marsha. "A Classic Case: Phillis Wheatley And Her Poetry." Early

American Literature 31.2 (1996):

103-132. Humanities Source.

Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

1

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/phillis-wheatley

|

|

|

|