|

LITR 4231 Early American

Literature Research Posts 2014 (research post assignment) Research Post 1 |

|

Thomas Dion

Loyalists are People Too

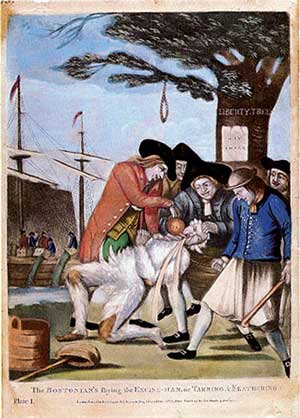

Does this picture look familiar? It does to me; it is a picture I saw

quite often in my history textbooks growing up, underneath the subheadings “Tar

and Feathering” or “Loyalist.” As with many kids, studying the revolution is

considered a Patriotic duty to be taken seriously, with respect, and

pride. Hence, the discussion of Loyalists and their reasons for staying loyal

was never brought forth in detail. (After all, it was American history and not

English history class). I remember my fifth grade teacher bringing the above

painting into focus one afternoon, pointing out how the Americans look devilish,

with snarling grins, carrying clubs, all while forcibly pouring hot tea down a

poor tarred-and-feathered man’s throat. At the time I thought this was nothing

more than propaganda, aimed at depicting the Americans negatively to gain

support at home, never did I think it was deserved criticism. The man’s name in

the painting is John Malcolm, and unlike the preconceived image I had of

Loyalists being King-loving-freedom-haters, he and like so many others, were

actually everyday people just like the rebellious revolutionaries, never

perfect, passionate, willing to

stand up for their beliefs, and at times, die for the ideals they believed in.

John Malcolm was not a loveable character to say the least, but should

that entail having hot tar torrentially covering his body? It seems a little

excessive to me, but I didn’t live back then. “The Worst Parade to Ever Hit the

Streets of Boston” by Nathaniel Philbrick tells the story leading up to this

fateful incident, revealing that John Malcolm was much more than just a customs

agent wanting the colonists to pay their taxes. Malcolm served as an officer in

the French and Indian war and thought of himself very highly in doing so,

claiming to have had two horses shot out from underneath of him and writing to

the King, “‘none could go further in the field of battle when the bullets flew

thickest, he was then in his element’” (Philbrick 1). The similarities to George

Washington’s military career in the French and Indian war should go to show that

at one time, even the founding fathers were Loyalists.

As with many Loyalists, Malcolm, took his allegiance seriously which made

him unpopular with the colonists. After a “genteel” tarring and feathering—when

the vigilantes allowed the victim to keep his clothes on—in the fall of 1774,

Malcolm had a reputation for being a stickler for the tax code. An unpopular

political stance with the rebel colonists, facing economic ruin, if their

smuggling business were to cease operation, that is to say, goes legitimate.

This tension culminated on January 25, 1774 when Malcolm lost his temper with a

careless sledding boy, then hit a man with his cane who tried to intervene, then

was dragged out of his house and subsequently dragged through the streets of

Boston (Philbrick 1-3). This time he did not get to keep his jacket on. Whether

or not tax collectors are revered or not, they do serve a purpose and John

Malcolm was just a man trying to do his job. This notion of performing one’s

duty to country is also positioned by Thomas Allen in his book Tories:

Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War. According to his

research, John Adams, in his own accounts estimates one third of the colonies'

population consisted of Loyalists, which means there was a large group of people

facing persecution if what was to happen to Malcolm reoccurred to others—just

doing their job (6, 154). Not all Loyalists chose to stay devoted to the crown

for monetary reasons; some continued for a theological purpose.

One of the doctrines of the Anglican Church is that the Head of England

is the Head of the Church. In “For God, King, and Country: Loyalism on the

Eastern Shore of Maryland during the American Revolution,” Barry Neville,

explores this component of religious freedom brought under attack by the

revolutionaries. If one of your core religious beliefs is to support the King,

then what happens when the political ties which connect the two are forcibly

severed? As Neville observes, “Attempts to interfere with freedom of worship

leads to a retrenchment in beliefs of the group under attack” (Neville 141).

Which meant the more the Anglicans were pushed into supporting the war, the more

they pushed back in unceasing loyalty to the sovereign dogma of the Anglican

Church (Neville 142). Say what you want to about taxes, if you are an ordinary

church member who has come to the colonies under the protection of the King in

connection with the church, why would you leave it in favor of those to abandon

your faith? Most Loyalists refused this notion, either returning back to England

or remaining as a pacifist observer. As such, those who stayed endured strict

regulations from the state governments requiring sermons and speeches to concern

only theological issues and not political issues (Neville 142). Although they

did not join in arms, these individuals helped their fellow Loyalist citizens by

providing medical aid to soldiers after battle (Neville 143). The Anglicans were

not the only social group to be alienated by the Patriot rebels into making the

decision to stay Loyal easier; there was another group, the American slaves,

whose recognition of themselves as striving for their own independence separate

from the colonists was in its infancy.

The slaves owned by both the Americans and British wanted their freedom

as well. These were the individuals who were truly being taxed without

representation. It was extremely surprising to myself when I found out through,

http://blackloyalist.com/canadiandigitalcollection/,

that the first emancipation of slaves, was not performed by Abraham Lincoln, but

in fact was issued by Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, in 1775. The

Proclamation was for any able bodied man to answer his call to arms, as he was

held up at Norfolk fending off a group of Patriots. The Proclamation stated that

any man joining the King’s army would be granted their freedom; countering this

was the Virginia Congress, who decreed it as “'striking against the foundations’

of Virginia’s society.” Within a month Dunmore had raised over eight hundred

troops; however, the honeymoon would be short-lived. Some of the slaves who

escaped were later returned under fugitive slave laws by Patriot and Loyalist

alike. Furthermore, after the war had ended, a majority of the escaped slaves

who had fought as soldiers were sold back into slavery in the Americas or

Caribbean sugar plantations. A small minority were able to relocate in Canada

but still received harsh racial treatment from fellow Loyalists. The turning

point came when a Black veteran from the war, Thomas Peters, began a movement

leading to the foundation of Sierra Leone and later Liberia. Each of these

countries was founded in order for escaped slave Loyalists to migrate back to

some kind of homeland, escaping racial bigotry in America in hopes of finding

their freedom.

A time of rebellion and dissent are hardly predictable and looking back,

from my station in time, affords many advantages. I now see that the American

Revolution was more than a war for freedom from an overbearing tyrant. It was a

culmination of events that included many people with justifiable reasons to

support their freedom from an overbearing mob mentality. Either way it was the

people who were involved, not just the governments—people who disagreed and

often times came out sounding hypocritical. Something can be learned from this

in today’s world as we try and push our beliefs of governance on the rest of the

world. That lesson is to simply listen to the other side; the more this occurs

the more bridges of understanding we build, instead of burning them with

inflammatory remarks. Patriot, Loyalist, Rebel, Tory: these are terms with

values imposed from without, used to separate and isolate, for examination or

discriminatory purposes. The suffering of these Loyalists has brought home to me

that war is hell, and can turn neighbors, friends, and family against one

another. Although I am now a member of the winning side of that conflict, I can

see the value in the ideals those individuals stood for, which is not at all

different from my own ideals, revealing to me that countries are but arbitrary

lines on a map, people are people, and we are all in this together.

Works Cited

Allen, Thomas B. Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War.

NY: HarperCollins, 2010. Print.

Canada’s Digital Collection. Black Loyalist: Our History, Our People.

Industry Canada.

Dawe, Philip. The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering.

1774, London. United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Web. 25

Mar. 2014.

Neville, Barry Paige. "For God, King, And Country: Loyalism On The Eastern Shore

Of Maryland During The American Revolution." International Social Science

Review 84.3/4 (2009): 135-156. Academic Search Complete. Web. 23 Mar.

2014.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. “The Worst Parade to Ever Hit the Streets of Boston.”

Smithsonianmag.com.

Smithsonian Institution, 1 April 2013. Web. 22 Mar. 2014.

|

|

|

|