|

LITR 4326 Early American Literature Model Assignments |

Final Exam Essays 2016 Sample answers for 2e. Teaching multiple texts through intertextuality and historicism . . . |

|

Burgundy Anderson

The Failings of Teaching in Blocks

Perhaps one of the fascinating ways in which literature is not studied is

intertextuality. The history surrounding most texts read in literature classes

is largely downplayed or outright ignored. The idea of studying texts together

brings out the biggest qualities and shortcomings of any given texts, and also

gives a greater appreciation for the context of the surrounding works. Some

texts work well standing on their own and do not require an understanding of the

time period in which they were written, but after this course I am convinced

these texts occur far less often than the average curriculum would have one

believe.

A

benefit of studying a text by itself is the ability to study that text very

deeply to create a new understanding. Even when we do this we lose the ability

to put a writing in context of other literature, both modern pieces and works

from the time period. We might gain a depth of understanding with one piece, but

we lose the ability to appreciate it within the grand scheme of things. I

appreciate Charlotte Temple more

having read Edgar Huntly because I

can understand better the writings of the time and the history in which

Charlotte Temple was written.

Reading literary masterpieces as self-contained units of study can unfortunately

create a false perception of an entire time period in a student. Previously, the

only major work I had read from early American literature was the Declaration of

Independence and parts of the U.S. Constitution. These writings gave me a false

understanding of body of work that exists from this time period. The ability to

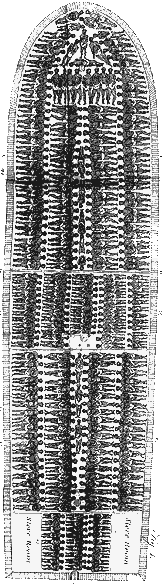

read such different works as creation stories, captivity narratives, religious

writings, and even enlightenment era pieces give me a richer understanding of

the history of America. I had assumed these writings would all prove to be

similar in nature, but each was so vastly different from the other that it

proved impossible to understand one without the other.

Within each subgenre of writing, the ability to read many different examples of

the style created a richer understanding of historicism behind the literature.

Particularly obvious was the study of creation stories of Europe, America, and

Africa. After reading Genesis and Columbusís letters, there are easy comparisons

to be made. The interplay of the Genesis storyline and the inevitably fall from

grace shows itself over and over through native origins stories and seems to be

a driving force in Columbusís letters. Cohen P. Landry was able to explain the

phenomenon very well in his essay

Bridging The Gap: Collective Ideas and Creations. The student discusses

particularly the Enlightenment period and how it developed its own distinct

style. He says of the periodís authors there is ďan unexplainable connection

that associated all of their ideas and visions.Ē He goes on to explain that the

underlying theme could be explained by the introduction of skepticism into

everyday religious life. The ability to study a time period as a whole, rather

than one piece of writing at a time, gives significance to the developments

made.

Historicism is significant because it makes students care. It can be easy for

most studying literature to accept different texts at face value as being

significate because everyone else agrees that they are significant. When

students read many different texts, it becomes apparent how and why the

literature we study matters. The study of the Puritans and the lives they led

seems to be only significant for understanding the past. However, when put it

context of the following movements, the way religious fervor grows and

ultimately turns to enlightenment reshapes the understanding modern Americans

have of our founders. Many say America was founded as a Christian nation, but

others are quick to point out Franklinís deism and the importance of having no

State religion. The study of these periods together create an understanding of

the harm that could be caused by either extreme.

An

argument could be made that longer texts, such as novels, should be studied on

their own. I think the distinction that should be made is that longer texts

should be read on their own. By reading a longer text by itself but comparing it

to other texts, students are better able to comprehend the realism of the

writings. But reading something on its own and studying it on its own are two

very different ideas. For example: Edgar

Huntly is a significant attempt to create an American Style in literature.

It was written not to sell copies or to have a moral lesson, but to create a

specific style of literature, as well as an understanding of style and

literature. When put in context of actual captivity narratives, like those of

Mary Rowlandson or Mary Jemison there is a distinct air of fiction about the

book. Connecting Edgar Huntly in its

fiction to actual experiences creates a unique understanding of the

unreliability of a narrator. If Edgar

Huntly was studied on its own, it could create a false perception of the

experiences of actual captives.

Intertextuality and Historicism go hand in hand because they are both so

significant. The way literature is studied piece by piece fragments the canon

and our understanding of writing. It also diminishes the value the selected

pieces hold. I would argue that in the fight to overhaul the current education

system the method of teaching literature in simple chunks with no regard to a

texts value beyond itself should be deeply considered. When we study many

different texts, we create a new overarching story which will serve to inspire

and inform in ways that no one piece ever can.

|

|

|

|