|

Craig White's Literature Courses Critical Sources

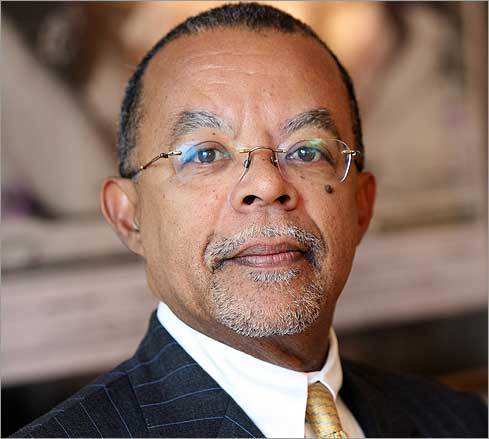

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. |

|

Gates, Henry

Louis, Jr.

In Search of Our Roots: How 19 Extraordinary African Americans Reclaimed

Their Past. NY: Crown, 2009.

Introduction: Family Matters

5 . . .

searching for my ancestry was always a fraught process, always a mix of joy,

frustration, and outrage, as the reconstruction of their history—individually

and collectively—must always be for any African American. I knew I had white

ancestors. My father was clearly part white, and his father looked like a

not-so-friendly version of

6 For us, for

those of us descended from the 455,000 Africans who arrived in this country

directly from Africa and indirectly from the Caribbean as slaves—80 percent of

whom had arrived here by 1800, 99.7 percent by 1820—it was the “trace-ability,”

as it were, that the evil genius of slavery sought to take away from us on

both

sides of the Atlantic, making us fragmented and not whole, isolated, discrete

parts, not pieces of fabric stitched together in a grand pattern, like some

living, breathing, mocha-colored quilt.

8 . . . the vast majority of us can trace at least one line

of our family back to the 1870 census, which was the first census taken after

the Civil War and is thus the first census in which all our ancestors appear as

people, as citizens with two names, as opposed to property, with no names.

9 The

roots of African American family trees extend only so far as the shores of the

10 Lost

until recently, that is. In the past decade, remarkable developments in DNA

testing and the retrieval and digitalization of archival records have

made it possible for us to begin to trace our families back further through

American history and, then, ultimately across the Atlantic. For the first time

since the seventeenth century, we are able, symbolically at least, to reverse

the Middle Passage. . . . With cells collected from the insides of our mouths,

geneticists can extract small sections of our DNA. The bases of the acids within

them form distinctive sequences know as haplotypes, which can then be compared

to DNA samples taken from other people around the world. A match means that

we’ve found someone with whom we share a common ancestor. And back in

12 Restoring the stories of the lives of the members of our

extended families can directly transform the way that historians reassemble the

larger narrative of the history of our people.

12 . . . perhaps the surprising secret of African American

genealogy is that every aspect of every family story, no matter how seemingly

trivial or insignificant, can be a revelation that reshapes how we understand

the entire sweep of the black experience in America.

Prefatory Notes on the African Slave Trade

16 Though the practices of slave owners varied, sometimes

significantly, in different eras and in different states and in different times,

slavery was, almost everywhere, a systemic effort to rob black human beings of

their very humanity itself—that is, of all the aspects of civilization that make

a human being “human”: names, birth dates, family ties, the freedom to be

educated and to worship, and the most basic sense of self-knowledge and

continuity of generations within one’s direct family.

17 Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database . . . a compilation of

the records kept by shipping companies involved in the slave trade. It offers

detailed information on 34,941 transatlantic slave-trading voyages that occurred

between 1514 and 1866. Compiled under the direction of David Eltis, with the

collaboration of Stephen D. Behrendt, Monolo Florentino, and David Richardson,

it is the largest uniform, consolidated database of its kind in the world.

According to

the database, before the slave trade ended in the

18 In fact,

more than half of us had ancestors living in the

19

Fifteen hundred languages are spoken on the African continent today. But the

ancestors of the African American people are surprisingly localized.

Linda Heywood and John Thornton have recently estimated that about fifty ethnic

groups in

20 Over the years the

blending of their different

ethnicities created the rich mixture—the pan-African identity—that is

African American culture today. . . . There were also, of course,

interracial mixtures with whites and with Native Americans—over half the African

American people today have at least one European great grandfather,

while that figure for a Native American great-grandparent is much, much less,

amounting to only about 5 percent—and all this intermixture contributes to who

we are today when we describe ourselves as “African Americans.”

20

5 percent of African Americans have at least

12.5 percent

Native American ancestry (equivalent of one great-grandparent).

21

58 percent of African Americans have at least 12.5

percent European ancestry (equivalent of one great-grandparent).

21

19.6 percent of African Americans have at least 25

percent European ancestry (equivalent of one grandparent).

21 1 percent of African Americans have at least 50 percent

European ancestry (equivalent of one parent).

21

2.7 percent of European Americans have at least

12.5 percent Native American Ancestry (equivalent of one great-grandparent).

21

Less than 1 percent of European Americans have at

least 12.5 percent West African ancestry (equivalent of one great-grandparent).

21 After

37

Well over half of all African American people have a white

ancestor. And while some are bothered by it, in my experience most, like Maya,

are not, which is, I think, an interesting indicator of

how willing we

are as a people to accept the racial complexity of our family histories rather

than to pretend to some sort of claim of African purity or embrace embarrassment

at how mixed our genetic makeup actually is.

![]()

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr.

Faces of

1-2 After I

joined the rest of

2 . . . the science of genetics could do for all African

Americans that which Alex Haley had done for himself: effectively reverse the

Middle Passage to recover every black family’s long-lost ancestral origins on

the African continent. To say that I was excited by this possibility is an

understatement.

4 [

5 . . . fully 35 percent of all other African American men

can also trace their paternal ancestors, their Y-DNA, to European men who

impregnated an African American female, most probably in the context of slavery.

5 It turns out that

the four or five “races” that

scholars postulated back then have absolutely no basis in biology. But it also

turns out that genetic variations among individuals are real and biologically

identifiable—and are infinitely more complex than anyone could have

imagined in the eighteenth century.

6 In

7 . . .

America is a giant ethnic mishmash—a series of

interlocking families, like my own, that are so thoroughly blended that any

notion of racial purity is naïve at best and a dangerous intellectual error at

worst.

8 Between 1820

and 1924, no fewer than thirty-six million people migrated to the

8 Yet immigrants themselves have routinely faced

discrimination, outright hostility, and sometimes severe hardships on the way to

earning the right to call themselves Americans.

![]()