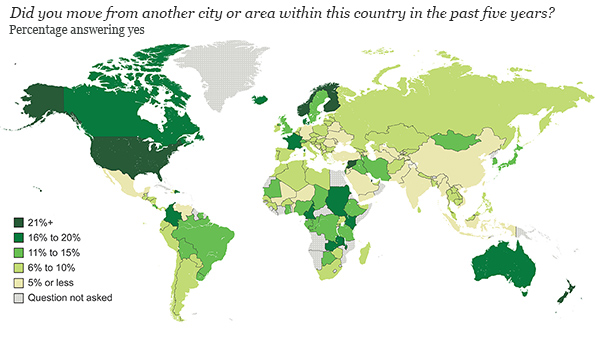

Iíve written recently about how Americans have been moving locations less and less since the 1970s. But letís put this in an international context. The United States is still one of the most mobile countries in the world:

That comes from

this new Gallup survey,

which found that 24 percent of Americans reported moving from their city or

area in the past five years. Thatís comparable to New Zealand (26 percent),

Finland (23 percent), and Norway (22 percent).

The other places where mobility

tends to be high are in conflict-ravaged countries like Iraq that have lots

of internal displacement. By contrast, thereís much much lower mobility in

China, where the

hukou system of

household registration effectively prevents rural workers from moving to

cities. The rate of migration there is less than 5 percent in the past five

years.

A few other notable findings in the Gallup report: Itís not surprising that a decent fraction of the moves are related to college and education ó which explains why younger people are more likely to move and wealthier countries often have more internal migrants. Another big reason for moving is job-related. And those moves donít always pan out: In Northern America, for example, internal migrants are more likely to participate in the workforce than those who have not moved. However, internal migrants are no more likely to be employed full time for an employer. They are more likely to be underemployed or unemployed than those who have not moved.

More recently, economists have

found that the rate of migration in the United States

has slowed down dramatically

since the 1970s ó a trend that continued through the Great Recession: ďThe

interstate migration rate in 2011 was 53 percent below its 1948-1971

average, while the rates of moving between counties within the same state

and of moving within the same county fell 44 and 36 percent, respectively,

over the same period.Ē

Itís still a mystery as to why this is. As a recent paper from the Federal Reserve Board argued, neither demographics nor the recession nor the rise in underwater mortgages can explain the drop.

That paperís theory is that American workers increasingly have less to gain from moving for a new job ó the wage boost that historically came with switching companies has declined over time. But that just creates a new mystery, since itís not clear why that wage boost is vanishing (a trend that, again, predated the recession).