|

Craig White's authors |

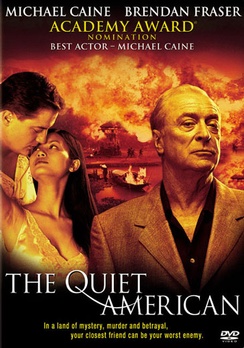

2002 film |

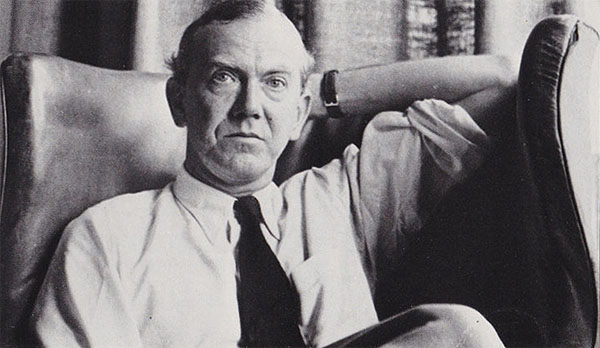

Graham Greene (1904-91) The Quiet American (1955) |

|

Graham Greene (1904-91), a popular and critically admired writer whose cosmopolitan career spanned most of the twentieth century, wrote a number of novels that associate him with the final decades of the British Empire or other colonial settings.

English or Commonwealth novelists of this long generation include George Orwell, E. M. Forster, Lawrence Durrell, Jean Rhys, Christopher Isherwood, W. Somerset Maugham, and Paul Scott.

Greene's fiction often became a basis for films, most prestigiously Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949); Brighton Rock (1947, 2010); and The End of the Affair (1955, 2004).

Greene's fiction remains significant in studies of 20th century British literature and also as Catholic literature.

For American readers, the novel The Quiet American (1955) remains prominent for its almost prophetic preview—and condemnation—of American involvement in Vietnam in the decade after the novel was written and set.

By extension, The Quiet American seems almost as prophetic of U.S. involvement in Iraq a generation later. (Graham's 1958 novel Our Man in Havana, filmed by Reed in 1959, likewise seems prescient of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.)

The Quiet American is set in Vietnam during the French-Indochina War (1945-54), during which Vietnamese nationalist and communist forces rebelled against French colonial rule.

-

French Indochina, established in 1887, eventually comprised present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Guangzhouwan province in Southeast China.

-

Accompanying historical backdrop: the concurrent Korean War (1950-53) involving South Korea supported by the United Nations and especially the USA versus North Korea supported by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. (America's Forgotten Wars)

![]()

The novel is skillfully and densely plotted, so that its many events would seem to require more than 180 pages.

The novel's historical interest is its superimposition of a change in colonial regimes (from the earlier colonialism of the British and French to the Neo-Colonialism of the USA) over a love triangle involving an aging British man, a Vietnamese woman, and a young American man.

The novel's narrator and protagonist is Thomas Fowler, a middle-aged British journalist separated from his wife in England and reporting on the French-Indochina War for a British publication. (From 1951 through 1954 Greene worked as a correspondent in Vietnam for The London Times and Le Figaro of Paris.)

Sharing Fowler's apartment in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) is 20-year-old Phuong, whose name means "Phoenix," a Vietnamese dance-garden girl.

Fowler meets the young Harvard-educated Alden Pyle, recently arrived as attache to the American legation in French Indochina. Inspired by an idealistic American foreign-affairs theorist, Pyle advocates—and promotes through clandestine activities—a "Third Force" that is neither the colonialism of the French and British nor the communism of the Vietnamese anti-colonial resistance.

Fowler warns Pyle that such theories show little knowledge of the actual conditions of colonizing and colonized peoples.

The ideological conflict becomes personal when Pyle meets Phuong and falls in love with her, then conspires with Phuong's scheming elder sister to separate Phuong from Fowler. As these intimate events unfold, Fowler and Pyle separately travel into northern Vietnam where French-Indochinese battles are flaring. They meet there at a Cao Dai temple and ceremony. During their journey together back to Saigon, they blunder into guerrilla battles where Fowler is seriously wounded and Pyle saves his life. . . .

From a conversation between Fowler and his native journalist assistant Dominguez (who is Catholic and maybe part Hindu):

"He [Dominguez] said, 'How much do you know of your friend Pyle?'

'Not very much. Our tracks cross, that's all. I haven't seen him since Tanyin.'

'What job does he do?'

'Economic Mission, but that covers a multitude of sins. I think he's interested in home-industries--I suppose with an American business tie-up. I don't like the way they keep the French fighting and cut out their business at the same time.'

'I heard him talking the other day at a party the Legation was giving to visiting Congressmen. They had put him on to brief them.'

'God help Congress,' I said, "he hasn't been in the country six months.'

'He was talking about the old colonial powers—England and France, and how you two couldn't expect to win the confidence of the Asiatics. That was where America came in now with clean hands.'

'Hawaii, Puerto Rico,' I said, 'New Mexico.'

'Then someone asked him some stock question about the chances of the Government here ever beating the Vietminh and he said a Third Force could do it. There was always a Third Force to be found free from Communism and the taint of colonialism—national democracy he called it; you only had to find a leader and keep him safe from the old colonial powers.'

(pp. 114-114, Penguin ed.)

![]()

Graham Greene, The Quiet American. 1955. NY: Penguin, 2004.

Robert Stone. Introduction. vii-xviii.

ix When he published The Quiet American, Graham Green was one of the few major writers in English with an ideological standpoint, presumably to be construed from his professed Catholicism. . . . The Quiet American, in its bitterness, came as an unpleasant surprise to most American Catholics. . . . Abroad, there were many of the left, including Catholics, who joined in what turned out to be, to us, a discomfitting general rejoicing at the sight of a master of moral nuance blasting the moralizing hyper-power, disdaining its wealth and careless certainty.

xi Alden Pyle, Fowler's rival for Phuong, is just one of the novel's Americans. All of these are innocent, Pyle most of all. To be innocent is to be bumptious and stupid, rude, provincial, inconsiderate, well-intentioned but at the same time conscienceless and murderous. . . . "I never met a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused," says Fowler of Pyle.

xv Fowler's jealousy over Phuong is a complicating motive, necessary to illustrate the impossibility of a purely disinterested act in this fallen world. Essentially when Fowler acts it is because, a wise French captain tells him in an opium den, "one has to take sides. If one is to remain human." . . . [Fowler:] "What's the good? He'll always be innocent, you can't blame the innocent, they are always guiltless. All you can do is control or eliminate them. Innocence is a kind of insanity."

xvii-xviii It is possible, as has often been done in America, to dismiss the characterization of Pyle. Assertions of American complicity with the bombers of Saigon in January 1952 do not really hold up. How is it then that every experienced American commentator on Vietnam to one degree or another admires The Quiet American? Fifty years after it was written, more than thirty years after the Vietnam war, it remains one of the great novels of the anticolonial struggle and the Cold War. During the Vietnam War, American journalists presented it to each other on arrival "in-country."

For one thing it is a model of the realist novel in the post-Conradian mode. Its story unfolds with a wonderful expertness and with the greatest economy. Its descriptive passages, its sense of Vietnam and Saigon, are richly pleasurable. . . .

xviii Green witnessed the beginning of a terrible mistake, a deadly mistake, the mistake of a great power armed to the teeth attempting to inflict its will in a part of the world to whose language and gestures it was tone deaf.