|

Craig White's authors |

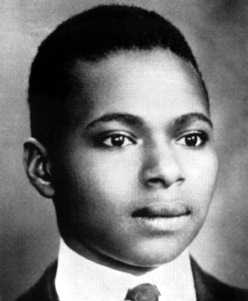

Cullen as teenager |

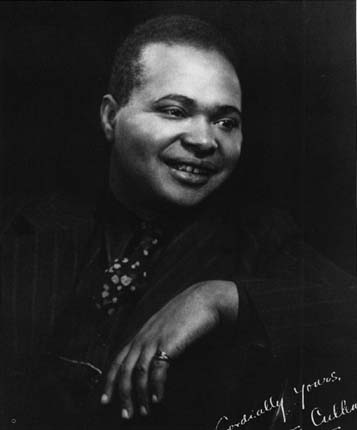

Countee Cullen (1903-1946) "For a Poet" "From the Dark Tower" "Fruit of the Flower" "Incident" "Yet do I Marvel" |

|

As a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance (1910s-30s) , Countee Cullen achieved brief but remarkable status as a unique poetic voice but also represented important tensions or conflicts of African American literature and culture.

Cullen's poetry explored one approach to the African American literary dilemma of whether to write of ethnic or social issues in a separate, distinct African American style, or to write of more universal subjects in a style derived from the traditions of English literature. In response, Cullen often wrote of black subjects or in black symbology but in European-American verse forms such as the sonnet or ballad. (In contrast, Cullen's Harlem Renaissance contemporary Langston Hughes wrote of black subjects in styles that often imitated African American musical genres like gospel, shouts, or blues.)

In his personal life, Hughes may have struggled to reconcile a gay or homosexual gender to the expectations of a child prodigy whose adopted home was closely connected to an African American church. (Broadly speaking, perennially sensitive subjects of GLBT identities are almost always heightened in cultures whose identities are already stressed.)

![]()

|

|

|

Biography

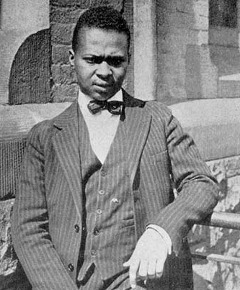

Countee Cullen, born 30 May in Louisville, Kentucky, was raised by his paternal grandparents. At their death, he was adopted (perhaps unofficially) at age 15 by Rev. F.A. Cullen, pastor of Salem Methodist Episcopal Church, Harlem's largest congregation, and later Harlem president of the NAACP.

Raised and nurtured in African American environments, Cullen excelled in New York's progressive public school system, particularly at DeWitt Clinton High School. In high school Cullen edited the school newspaper, won a citywide poetry contest, and learned European-American literary styles that became models for most of his creative work. Continuing his studies at New York University, Cullen won its Witter Bynner Poetry Prize and contests in Poetry magazine. In 1927 Cullen completed a master's degree in English and French at Harvard University.

In the mid- to late 1920s Cullen gained a high profile in the Harlem Renaissance, publishing poems in national periodicals as well as his first book of poetry (Copper, 1925) and editing Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets (1927), in whose preface he wrote that "negro poets, dependent as they are on the English language, may have more to gain from the rich background of English and American poetry than from any nebulous atavistic yearnings toward an African inheritance."

In these attitudes and in his own poems' practices, Cullen fulfilled many aspirations of the previous generation of black American intellectuals such as W. E. B. DuBois and James Weldon Johnson, both of whom praised his work. As a poet accomplished in traditional European forms who yet gives voice to African American concerns, Cullen may be considered in the same tradition as earlier Black American poets Phillis Wheatley (1753-84) and Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906).

In 1928 Cullen won a Guggenheim fellowship to write poetry in France. Also that year a great social gathering of Harlem's intellectual elite witnessed his marriage to Nina Yolande DuBois, the daughter of W. E. B. DuBois, the president of the NAACP and a major author and sociologist in the African American community. The couple divorced in 1930 amid rumors of Cullen's involvement with a leading figure of Harlem's gay elite.

After 1929 Cullen's production of verse dropped off

dramatically, limited to his translation of Euripides' play

Medea accompanied by

"some poems" of his own. The Great Depression of that year inevitably repressed

the development of the Harlem Renaissance. In the late 1930s, Cullen like Hughes

increasingly worked in drama, both for its potential financial returns and the

possibilities of a larger social impact. In 1940, Cullen married Ida Mae

Robertson, whom he had known for ten years, and began teaching at Frederick

Douglass Junior High, where

his student was James Baldwin (1924-1987), later a distinguished novelist

(Go Tell It on the Mountain,

1953) and essayist (Notes of a Native Son,

1955). He also continued work on dramatic

endeavors. On 9 January 1946 Cullen died of high blood pressure and uremic

poisoning. That spring "St. Louis Woman,"

which Cullen and Arna Bontemps had adapted from Bontemps's novel, premiered on

Broadway and made singer Pearl Bailey a star.

selected publications:

Color (1925,

poetry)

Copper Sun

(1927,

poetry)

The Ballad of the Brown Girl

(1928,

poetry)

The Black Christ and Other Poems

(1929,

poetry)

One Way to Heaven

(1932, novel)

The Medea and Some Poems

(1935,

poetry)

(With Arna Bontemps) St. Louis Woman (musical adaptation of Bontemps's novel God Sends Sunday; first produced at Martin Beck Theater in New York City, March 30, 1946), published in Black Theatre, edited by Lindsay Patterson, Dodd, 1971.

On These I Stand: An Anthology of the Best Poems of Countee Cullen (includes Dear Friends and Gentle Hearts, Christus natus est, and some previously unpublished poems), Harper, 1947.

My Soul's High Song: The Collected Writings of Countee Cullen, Voice of the Harlem Renaissance, edited, introduction by Gerald Early, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1991.

Internet Sources:

http://www.biography.com/people/countee-cullen-38950

http://www.nndb.com/people/339/000113000/

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/countee-cullen

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/cullen/life.htm

Backgrounds:

Of two poems by Countee Cullen--"For a Poet" & "Incident"--the second is more widely anthologized.

"American Minority Literature" must balance or decide how to teach literature and culture, either separately or together.

Exercise:

What different appeals do the two poems by Countee Cullen satisfy?

How to resolve these different appeals in teaching?

In "Incident," is it OK to say the N-word if it's necessary to complete the rhyme?