Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

-

Not a critical or scholarly text but a reading text for a seminar

-

Gratefully copied and adapted from http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/ConDark.html

-

Changes may include paragraph divisions, highlights, spelling updates, bracketed annotations, & elisions (marked by ellipses . . . )

|

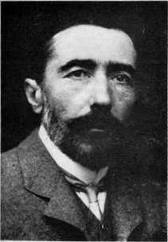

Heart of Darkness (1899, 1902) by Joseph Conrad (1857-1924)

|

Heart of Darkness at Kazuya Akimoto Art Museum |

Heart of Darkness, part one, due 17 November 2015

Heart of Darkness, part two, due 24 November 2015

Chinua Achebe, "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness" (for both meetings)

George Washington Williams, “An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II,

King of the Belgians

and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo . . . " (1890)

(optional —report by African American activist on the Congo near time of

Conrad's journey)

Caryl Phillips interview with Chinua Achebe

Instructor's Introduction

Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) ranks as a unique yet supreme author of English fiction whose novella Heart of Darkness (1899, 1902) is a standard assignment for secondary and college students in the United States and a brief masterpiece in the styles and issues of early Modernism. In the 1970s Heart of Darkness became more widely known for providing a narrative framework for Apocalypse Now (1979), a landmark film on the US-Vietnam War. Kurtz’s dying exclamation “The horror! The horror!” remains a standard allusion for educated readers of English.

Like other Modernist texts of the early 20th century including T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), Yeats’s “The Second Coming” (1920), or Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time (1924), Heart of Darkness exposes and challenges assumptions of European civilization at a time when European imperialism was escalating to World War. Despite this skeptical Modernist framework, Postcolonial Studies challenges any colonial text for its propagation of Western cultural biases.

For many readers the dualistic dark-and-light symbolism of Heart of Darkness may seem as natural or “universal” a color code as night and day, but a person of color from “the dark continent” of Africa might not accept the value system implicit in such a scheme—especially when the narrator’s language describes African natives with racial slurs. Achebe's 1975 article, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness," remains the most prestigious and provocative articulation of the position that Heart of Darkness embodies imperialistic European values as much or more than it questions them.

As with American classics that stir similar controversies, such as Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1886), a standard defense of Conrad’s racist language is that it reflects actual historical conditions. Such rationales may overlook the survival of such language and ideologies despite decades of purported progress. Can a Western classic like Heart of Darkness be a great work of art anyway? At what cost and benefit?

Beyond race and ethnicity, gender studies may also suspect Heart of Darkness for its predominantly male characters and ethos—though this situation may also be empirically true to the literary-historical conditions of maritime fiction and the frontiers of empire-building. Overall, Marlow’s condescending references to women characters and feminine mentalities may ultimately be as irresolvable as its racial entanglements.

These problems add to

difficulties students find in appreciating Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to

begin with.

![]()

Is it possible to read the novel without necessarily making a racist villain out of Marlow?

Potential reasons to admire Marlow:

He goes on the journey to learn and never abandons that attitude. Aside from a motivation to learn, As with some characters in Hemingway's fiction, Marlowe's action is often led by a work ethic that leads him to judge colonizers and colonized by their honest attitudes toward work. Thus he often admires the natives for their adaptability and seriousness, in contrast to his fellow colonizers' fantastic frames of mind and lack of accountability.

Despite his language describing Africans, he feels pity and admiration for them and regards his fellow colonists with a healthy irony. The more Marlow sees of Kurtz, the more despairing his account of colonial exploitation.

![]()

Potential reasons to admire Heart of Darkness:

Achebe on "intoxication of style": English is Conrad's third language; does the aural, dream-like beauty of his prose reflect an outsider's fascination?

Kurtz as Nietzschean Superman, heroic conqueror and Promethean light-bringer—which the narrative exposes as rapacious nonsense

Again Marlow registers the standard self-other horror of cannibalism, but compared to Crusoe, Marlow's perception is more nuanced and ready to admire its practitioners.

![]()

Potential reasons to admire style:

As in much Modernism, the prose’s indirectness and obscurity may be defended as representing the confusion of experience and mental-verbal expression

Limits of Marlow’s perceptions, even as revealed in first-person narrative—cf. Crusoe on Friday, or characters in Simba.

Instructor's questions:

from Obj. 2a: Can Colonizers be understood as other than villains? Does dehumanizing the other automatically dehumanize the oppressor? (Moral opposition increases drama, but moral relativism cultivates relations.)

How does Heart of Darkness exemplify Modernist fiction? (Compare Faulkner, Joyce, Woolf)

Can the color-code of light-dark symbolism be shifted from skin color to perception or the work ethic? (work ethic also described as efficiency)

That is, the Enlightenment may fairly be associated with Europe (and its light-skinned peoples), but may its meanings be extended to more trans-human values? (which may in turn be associated with European codes like transparency and the Protestant Work Ethic).

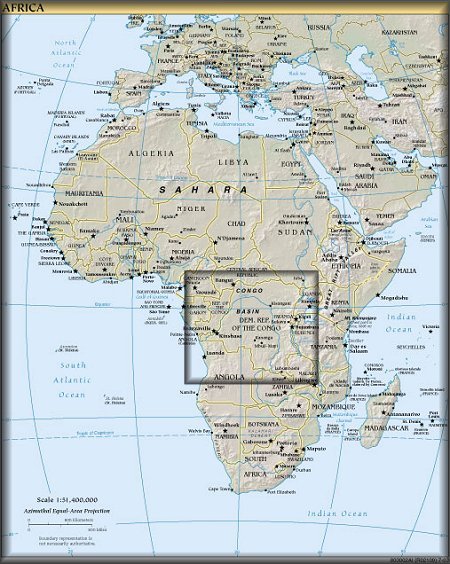

Colonial-Postcolonial History of the Congo Region

from Congo Free State > Belgian Congo > Democratic Republic of Congo

|

Belgium, Kingdom / Nation in Europe |

|

In 1885 the Berlin Conference of European states granted a large tract of uncolonized land in Africa's Congo region to King Leopold II of Belgium, who organized the Congo Free State under philanthropic pretenses.

In 1889 Joseph Conrad took employment as a steamboat pilot in the Congo Free State, where he witnessed the rapacious exploitation of the Congo region's resources and its native peoples.

Conrad befriended Henry Casement, an Irish journalist, English diplomat, and international human rights activist. The latter's "Casement Report" (1904) exposed abuses by the Congo Free State, which then reorganized as "the Belgian Congo" —no longer under King Leopold's personal control but rather that of the Belgian government.

Conditions improved, but World War 2 weakened European colonial powers. In 1960 the Republic of the Congo received its independence, to be renamed Zaire in 1966, changing again in 1996 to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Conditions in the Congo region remain unstable, with the familiar postcolonial problems resulting from an artificial nation created by outsiders from a collection of ethnic groups and languages, plus conflicts from bordering nations (e.g., Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Sudan) spilling over.

|

|

|