|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

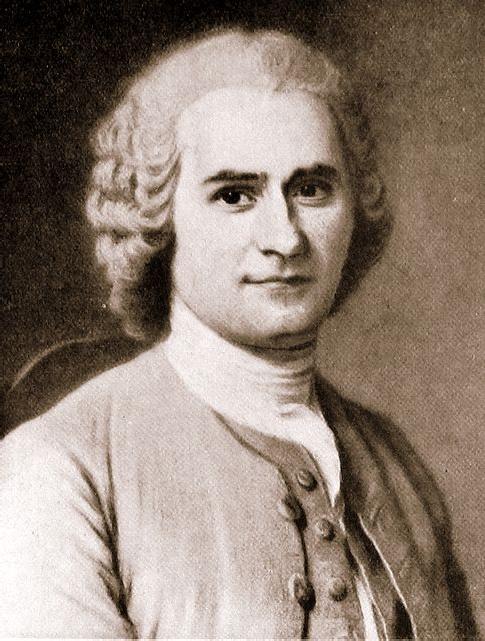

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) on Robinson Crusoe from Emile, or On Education (1762) |

|

. . . I hate books; they only teach us to talk about things we know nothing about. Hermes, they say, engraved the elements of science on pillars lest a deluge should destroy them. Had he imprinted them on men's hearts they would have been preserved by tradition. Well-trained minds are the pillars on which human knowledge is most deeply engraved.

Is there no way of correlating so many lessons scattered through so many books, no way of focussing them on some common object, easy to see, interesting to follow, and stimulating even to a child? Could we but discover a state in which all man's needs appear in such a way as to appeal to the child's mind, a state in which the ways of providing for these needs are as easily developed, the simple and stirring portrayal of this state should form the earliest training of the child's imagination.

Eager philosopher, I see your own imagination at work. Spare yourself the trouble; this state is already known, it is described, with due respect to you, far better than you could describe it, at least with greater truth and simplicity. Since we must have books, there is one book which, to my thinking, supplies the best treatise on an education according to nature. This is the first book Emile will read; for a long time it will form his whole library, and it will always retain an honoured place. It will be the text to which all our talks about natural science are but the commentary. It will serve to test our progress towards a right judgment, and it will always be read with delight, so long as our taste is unspoilt. What is this wonderful book? Is it Aristotle? Pliny? Buffon? No; it is Robinson Crusoe.

Robinson Crusoe on his island, deprived of the help of his fellow-men, without the means of carrying on the various arts, yet finding food, preserving his life, and procuring a certain amount of comfort; this is the thing to interest people of all ages, and it can be made attractive to children in all sorts of ways. We shall thus make a reality of that desert island which formerly served as an illustration. The condition, I confess, is not that of a social being, nor is it in all probability Emile's own condition, but he should use it as a standard of comparison for all other conditions. The surest way to raise him above prejudice and to base his judgments on the true relations of things, is to put him in the place of a solitary man, and to judge all things as they would be judged by such a man in relation to their own utility.

This novel, stripped of irrelevant matter, begins with Robinson's shipwreck on his island, and ends with the coming of the ship which bears him from it, and it will furnish Emile with material, both for work and play, during the whole period we are considering. His head should be full of it, he should always be busy with his castle, his goats, his plantations. Let him learn in detail, not from books but from things, all that is necessary in such a case. Let him think he is Robinson himself; let him see himself clad in skins, wearing a tall cap, a great cutlass, all the grotesque get-up of Robinson Crusoe, even to the umbrella which he will scarcely need. He should anxiously consider what steps to take; will this or that be wanting? He should examine his hero's conduct; has he omitted nothing; is there nothing he could have done better? He should carefully note his mistakes, so as not to fall into them himself in similar circumstances, for you may be sure he will plan out just such a settlement for himself. This is the genuine castle in the air of this happy age, when the child knows no other happiness but food and freedom.

What a motive will this infatuation supply in the hands of a skilful teacher who has aroused it for the purpose of using it. The child who wants to build a storehouse on his desert island will be more eager to learn than the master to teach. He will want to know all sorts of useful things and nothing else; you will need the curb as well as the spur. Make haste, therefore, to establish him on his island while this is all he needs to make him happy; for the day is at hand, when, if he must still live on his island, he will not be content to live alone, when even the companionship of Man Friday, who is almost disregarded now, will not long suffice. . . .

![]()

![]()

—

[ ] x