Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

Of Plymouth Plantation

Chapter Nine. Of Their Voyage, and How They Passed the Sea; and of Their Safe Arrival at Cape Cod |

|

[Instructor’s note: This chapter briefly describes the Pilgrims’ 65-day crossing of the Atlantic and their search for a proper area to settle.]

[¶9.1] September 6 [1620]. These troubles being blown over, and now all being compact together in one ship, they put to sea again with a prosperous wind, which continued divers [several] days together, which was some encouragement unto them; yet, according to the usual manner, many were afflicted with seasickness.

[¶9.2] And I may not omit here a special work of God's providence. There was a proud and very profane young man, one of the seamen, of a lusty, able body, which made him the more haughty; he would always be contemning [scorning] the poor people in their sickness and cursing them daily with grievous execrations [oaths]; and did not let [hesitate] to tell them, that he hoped to help to cast half of them overboard before they came to their journey's end, and to make merry with what they had; and if he were by any gently reproved, he would curse and swear most bitterly. But it pleased God before they came half seas over, to smite this young man with a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner, and so was himself the first that was thrown overboard. Thus his curses light on his own head, and it was an astonishment to all his fellows for they noted it to be the just hand of God upon him. . . .

[¶9.3] After they had enjoyed fair winds and weather for a season, they were encountered many times with cross winds, and met with many fierce storms, with which the ship was shroudly [wickedly] shaken, and her upper works made very leaky; and one of the main beams in the midships was bowed and cracked, which put them in some fear that the ship could not be able to perform the voyage. So some of the chief of the company, perceiving the mariners to fear the sufficiency of the ship, as appeared by their mutterings, they entered into serious consultation with the master and other officers of the ship, to consider in time of the danger; and rather to return than to cast themselves into a desperate and inevitable peril. And truly there was great distraction and difference of opinion amongst the mariners themselves; fain would they do what could be done for their wages’ sake, (being now half the seas over,) and on the other hand they were loath to hazard their lives too desperately. But in examining of all opinions, the master and others affirmed they knew the ship to be strong and firm under water; and for the buckling [reinforcement, strengthening] of the main beam, there was a great iron screw the passengers brought out of Holland [this “great iron screw” may have been part of the printing press the Pilgrims brought with them from Leiden—another victory for Puritan literacy?], which would raise the beam into his place; the which being done, the carpenter and master affirmed that with a post put under it, set firm in the lower deck, and otherways bound, he would make it sufficient. . . .

map of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, with Plymouth on Bay (Boston further North)

[¶9.4] But to omit other things (that I may be brief) after long beating [navigation] at sea they fell with that land which is called Cape Cod; the which being made and certainly known to be it, they were not a little joyful. After some deliberation had amongst themselves and with the master of the ship, they tacked about and resolved to stand for the southward (the wind and weather being fair) to find some place about Hudson's River [in modern New York state] for their habitation. But after they had sailed that course about half the day, they fell amongst dangerous shoals and roaring breakers, and they were so far entangled therewith as they conceived themselves in great danger; and the wind shrieking upon them withal, they resolved to bear up again for the Cape and thought themselves happy to get out of those dangers before night overtook them, as by God's good providence they did. And the next day they got into the Cape Harbor [now Provincetown Harbor] where they rid in safety. . . .

[¶9.5] Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element. And no marvel if they were thus joyful, seeing wise Seneca was so affected with sailing a few miles on the coast of his own Italy, as he affirmed, that he had rather remain twenty years on his way by land than pass by sea to any place in a short time, so tedious and dreadful was the same unto him. [Note again that Bradford cites not only biblical scripture but secular classical sources, an example of the “Christian Humanism” of the Renaissance.]

[¶9.6] But here I cannot but stay and make a pause, and stand half amazed at this poor people's present condition; and so I think will the reader, too, when he well considers the same. Being thus passed the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles before in their preparation (as may be remembered by that which went before), they had now no friends to welcome them nor inns to entertain or refresh their weatherbeaten bodies; no houses or much less towns to repair to, to seek for succor.

[¶9.7] It is recorded in Scripture [Acts 28.2, where St. Paul is shipwrecked on the Mediterranean Island of Malta] as a mercy to the Apostle and his shipwrecked company that the barbarians showed them no small kindness in refreshing them, but these savage barbarians [American Indians], when they met with them (as after will appear) were readier to fill their sides full of arrows than otherwise. And for the season it was winter, and they that know the winters of that country know them to be sharp and violent, and subject to cruel and fierce storms, dangerous to travel to known places, much more to search an unknown coast.

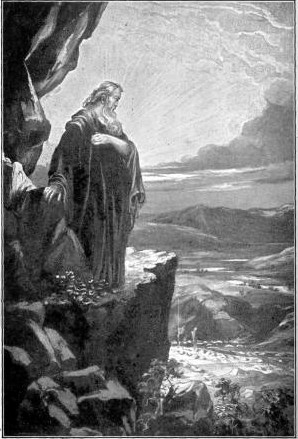

[¶9.8] Besides, what could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men and what multitudes there might be of them they knew not. Neither could they, as it were, go up to the top of Pisgah to view from this wilderness a more goodly country to feed their hopes; . . .

[typology: though negative, Bradford compares the Pilgrims’ experience to that of the Jews in Exodus—in this case, when Moses went to the top of Mount Pisgah (Mount Nebo) and saw the Promised Land that he would not live to enter.

Deuteronomy 34: 1And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho. And the LORD shewed him all the land of Gilead, unto Dan . . .

4And the LORD said unto him, This is the land which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, saying, I will give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to see it with thine eyes, but thou shalt not go over thither.

5So Moses the servant of the LORD died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of the LORD.

Moses on Mount Pisgah, seeing the Promised Land

[¶9.9]; for which way soever they turned their eyes (save upward to the heavens) they could have little solace or content in respect of any outward objects. For summer being done, all things stand upon them with a weatherbeaten face, and the whole country, full of woods and thickets, represented a wild and savage hue. If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed and was now as a main bar and gulf to separate them from all the civil parts of the world. [An example of Old World immigration as “cultural guillotine” in which the cost and difficulty of immigration imply “no going back” and a commitment to the new country. In contrast, more recent New World immigration to the USA from other parts of the Western Hemisphere (Central and South America, the Caribbean) appear not to have the same dynamic, as immigrants may walk, drive, or fly back and forth, and communications have improved.] . . .

[¶9.10] Let it also be considered what weak hopes of supply and succor [relief] they left behind them, that might bear up their minds in this sad condition and trials they were under; and they [their hopes of relief] could not but be very small. It is true, indeed, the affections and love of their brethren at Leiden was cordial and entire towards them, but they had little power to help them or themselves . . . .

[¶9.11] What could now sustain them but the Spirit of God and his grace? May not and ought not the children of these fathers rightly say:

Our fathers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this wilderness; but they cried unto the Lord, and he heard their voice and looked on their adversity, etc. Let them therefore praise the Lord, because he is good: and his mercies endure forever. Yea, let them which have been redeemed of the Lord, shew how he hath delivered them from the hand of the oppressor. When they wandered in the desert wilderness out of the way, and found no city to dwell in, both hungry and thirsty, their soul was overwhelmed in them. Let them confess before the Lord his lovingkindness and his wonderful works before the sons of men.