Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

Of Plymouth Plantation

from Chapters 7 & 8: leaving Holland, back to England, on to America |

|

from Chapter 7. 0f their departure from Leyden, and other things thereabout, with their arrival at South Hampton, where they all met together, and took in their provisions.

[∂7.1] At length, after much travail [labor] and these debates, all things were got ready and provided. A small ship was bought, and fitted in Holland, which was intended as to serve to help to transport them, so to stay in the country and attend upon fishing and such other affairs as might be for the good and benefit of the colony when they came there. Another [ship, the Mayflower] was hired at London, of burden [capacity] about nine score [180 tons]; and all other things got in readiness.

[∂7.2] So being ready to depart, they had a day of solemn humiliation, their pastor taking his text from Ezra 8.21.

And there at the river, by Ahava, I proclaimed a fast, that we might humble ourselves before our God, and seek of him a right way for us, and for our children, and for all our substance.

Upon which he spent a good part of the day very profitably, and suitable to their present occasion. The rest of the time was spent in pouring out prayers to the Lord with great fervency, mixed with abundance of tears.

[∂7.3] And the time being come that they must depart, they were accompanied with most of their brethren out of the city, unto a town sundry miles of called Delftshaven, where the ship lay ready to receive them. So they left that goodly and pleasant city [Leiden, Holland], which had been their resting place nearly twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on these things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits.

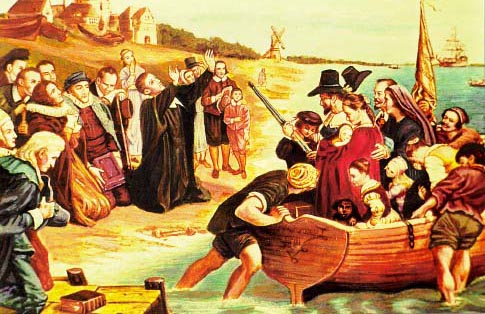

[∂7.4] When they came to the place they found the ship and all things ready; and such of their friends as could not come with them followed after them, and sundry [others] also came from Amsterdam to see them shipped and to take their leave of them. That night was spent with little sleep by the most, but with friendly entertainment and Christian discourse and other real expressions of true Christian love. The next day, the wind being faire, they went aboard, and their friends with them, where truly doleful was the sight of that sad and mournful parting; to see what sighs and sobs and prayers did sound amongst them, what tears did gush from every eye, and pithy speeches pierced each heart; that sundry [some] of the Dutch strangers that stood on the key as spectators, could not refrain from tears. Yet comfortable and sweet it was to see such lively and true expressions of dear and unfeigned love.

[∂7.5] But the tide (which stays for no man) calling them away that were thus loath to depart, their Reverend pastor falling down on his knees, (and they all with hirn,) with watery cheeks commended them with most fervent prayers to the Lord and his blessing. And then with mutual embraces and many tears, they took their leaves one of a other, which proved to be the last leave to many of them. . . .

Chapter 7 continues: from a letter from Pastor John Robinson

[Instructorís note: In the first paragraph, the Pilgrims debate the relations of the individual and community, a continuing issue for American culture.

The second paragraph discusses political government with some relevance to democratic rule:

-

the Pilgrims were working-class and middle-class people, so that no ďeminentĒ leaders would appear among them

-

In choosing their leaders, the Pilgrims were enacting Godís will, and should obey their leaders in a similar spirit.

-

Self-government!]

[∂7.6] . . . A fourth thing there is carefully to be provided for, to wit, that with your common employments you join common affections truly bent upon the general good, avoiding as a deadly plague of your both common and special comfort all retiredness of mind for proper advantage, and all singularly affected any manner of way; let every man repress in him self and the whole body in each person, as so many rebels against the common good, all private respects of menís selves, not sorting with the general convenience. And as men are careful not to have a new house shaken with any violence before it be well settled and the parts firmly knit, so be you, I beseech you, brethren, much more careful, that the house of God which you are, and are to be, be not shaken with unnecessary novelties or other oppositions at the first settling thereof.

[∂7.7] Lastly, whereas you are become a body politic, using amongst yourselves civil government, and are not furnished with any persons of special eminence above the rest, to be chosen by you into office of government, let your wisdom and godliness appear, not only in choosing such persons as do entirely love and will promote the common good, but also in yielding unto them all due honor and obedience in their lawful administrations; not beholding in them the ordinariness of their persons, but Godís ordinance for your good, not being like the foolish multitude who more honor the gay coat, than either the virtuous mind of the man, or glorious ordinance of the Lord. But you know better things, and that the image of the Lordís power and authority which the magistrate beareth is honorable, in how mean [contemptible] persons soever. And this duty you both may the more willingly and ought the more conscionably to perform, because you are at least for the present to have only them for your ordinary governors, which yourselves shall make choice of for that work.

[∂7.8] Sundry other things of importance I could put you in mind of, and of those before mentioned, in more words, but I will not so far wrong your godly minds as to think you heedless of those things, there being also diverse among you so well able to admonish both themselves and others of what concerneth them. These few things therefore, and the same in few words, I do earnestly commend unto your care and conscience, joining therewith my daily incessant prayers unto the Lord, that he who hath made the heavens and the earth, the sea and all rivers of waters, and whose providence is over all his works, especially over all his dear children for good, would so guide and guard you in your ways, as inwardly by his Spirit, so outwardly by the hand of his power, as that both you and we also, for and with you, may have after matter of praising his name all the days of your and our lives. Fare you well in him in whom you trust, and in whom I rest.

An unfeigned well-willer of your happy success in this hopeful voyage,

JOHN ROBINSON.

Chapter Eight. Of the troubles that befell them on the coast, and at sea being forced, after much trouble, to leave one of two ships and some of their company behind them.

[∂8.1] Being thus put to sea they had not gone far, but Mr. Reynolds, the master of the lesser ship, complained that he found his ship so leaky as he dared not put further to sea till she was mended. So the master of the bigger ship (called Mr. Jonas) being consulted with, they both resolved to put into Dartmouth and have her there searched [inspected] and mended, which accordingly was done, to their great charge and loss of time and a faire wind.

[∂8.2] She [the smaller ship] was here thoroughly searched from stem to stern, some leaks were found and mended, and now it was conceived by the workmen and all, that she was sufficient, and they might proceed without either fear or danger. So with good hopes from hence, they put to sea again, conceiving they should go comfortably on, not looking for any more lets [obstructions] of this kind; but it fell out otherwise, for after they were gone to sea again above one hundred leagues without [beyond] the Landís End, holding company together [conferring] all this while, the master of the small ship complained his ship was so leaky as he must bear up or sink at sea, for they could scarce free her with much pumping.

[∂8.3] So they carne to consultation again, and resolved both ships to bear up back again and put into Plymouth [English coastal town], which accordingly was done. But no special leak could be found, but it was judged to be the general weakness of the ship, and that she would not prove sufficient for the voyage. Upon which it was resolved to dismiss her and part of the company, and proceed with the other ship. The which (though it was grievous, and caused great discouragement) was put in execution. So after they had took out such provision as the other ship could well stow, and concluded both what number and what persons to send back, they made another sad parting, the one ship going back for London, and the other was to proceed on her voyage. Those that went back were for the most part such as were willing so to do, either out of some discontent, or fear they conceived of the ill success of the voyage, seeing so many crosses befall, and the year time so far spent; but others, in regard of their own weakness, and charge of many young children, were thought least useful, and most unfit to bear the brunt of this hard adventure; unto which work of God, and judgment of their brethren, they were contented to submit. And thus, like Gideonís army, this small number was divided, as if the Lord by this work of his providence thought these few too many for the great work he had to do. . . .