Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

Of Plymouth Plantation

from Chapter Nineteen. [Intercolonial

trade; the Indians' “wampum bubble”; Morton & the May-Pole of Merry

Mount] |

|

Instructor’s notes on implicit typology

Negative reference to Indian women for consorts—compare how Jews were not to marry Canaanites

May-Pole and Dagon as “idols” in contrast to Invisible-Universal God of Jews (and Moslems)

Issues of different status: dominant culture / minority

Unequal status—servants / slaves to Virginia

Unequal trade, esp. with high technology

and weaponry

[¶19.1] This year the Dutch sent again unto them from their plantation, both kind letters, and also diverse commodities as sugar, linen cloth, Holland finery and coarser stuffs, etc. They [the Dutch traders] came up with their bark to Manomet, to their house there, in which came their Secretary Racier; who was accompanied with a noise of trumpeters, and some other attendants, and desired that they would send a boat for him, for he could not travel so far over land. So they sent a boat to Scusett, and brought him to the plantation, with the chief of company. And after some few days’ entertainment, he turned to his bark, and some of them went with him and bought sundry of his goods; after which beginning thus they sent oftentimes to the same place, and had intercourse together for diverse years; and amongst other commodities they vended much tobacco for linen cloths, stuffs, etc., which was a good benefit to the people, till the Virginians found out their plantation.

[¶19.2] But that which turned most to their [traders’] profit, in time, was an entrance into the trade of wampumpeag [wampum, a sea shell used by various eastern woodland tribes for currency, décor, and communication]; for they now bought about 50 pounds worth of it of them; and they told them how vendible it was at their Fort Orania [Fort Orange, now Albany NY]; and did persuade them they would find it so at Kennebec; and so it came to pass in time, though at first it stuck, and it was 2 years before they could put of this small quantity, till the inland people knew of it; and afterwards they could scarce ever get enough for them, for many years together. And so this, with their other provisions cut off their trade quite from the fishermen, and in great part from other of the straggling planters.

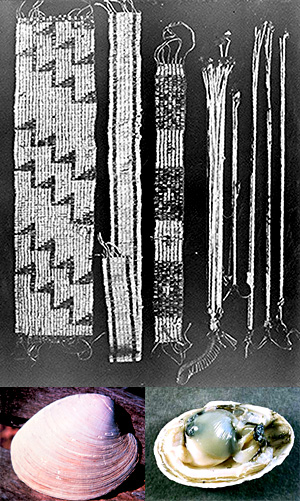

Shells for Wampum

[¶19.3] And strange it was to see the great alteration it made in a few years among the Indians themselves; for all the Indians of these parts, and the Massachusetts, had none or very little of it, but the sachems and some special persons that wore a little of it for ornaments. Only it was made and kept among the Narragansetts and Pequots, which grew rich and potent by it, and these people were poor and beggarly, and had no use of it. Neither did the English of this plantation, or any other in the land, till now that they had knowledge of it from the Dutch, so much as know what it was, much less that it was a commodity of that worth and value.

[¶19.4] But after it [wampum] grew thus to be a commodity in these parts, these [local] Indians fell into it also, and to learn how to make it; for the Narragansetts do gather the shells of which they make it from their shores. And it hath now continued a current commodity about this 20 years, and it may prove a drug in time. In the meantime it makes the Indians of these parts rich and powerful and also proud thereby; and fills [provides] them with pieces [firearms], powder [gunpowder], and shot [ammunition ], which no laws can restrain, by reason of the baseness of sundry unworthy persons, both English, Dutch and French, which may turn to the ruin of many. Hitherto the Indians of these parts had no pieces [firearms] nor other arms but their bows and arrows, nor of many years after; nether dared they scarce handle a gun, so much were they afraid of them; and the very sight of one (though out of kilter) was a terror unto them. But those Indians to the east parts which had commerce with the French, got pieces [firearms] of them, and they in the end made a common trade of it; and in time our English fishermen, led with the like covetousness, followed their example, for their own game; but upon complaint against them, it pleased the king’s majesty to prohibit the same by a strict proclamation, commanding that no sort of arms, or munitions, should by any of his subjects be trade with them [the Indians].

[Captain Morton of Merry-Mount]

[¶19.5] About some three or four years before this time, there came over one Captain Wollaston, (a man of pretty parts) and with him three or four more of some eminence, who brought with them a great many servants, with provisions and other implements for to began a plantation; and pitched themselves in a place within the Massachusetts, which they called, after their Captain’s name, Mount-Wollaston. Amongst whom was one Mr. Morton, who, it should seems, had some small adventure (of his own or other men’s) amongst them; but had little respect amongst them, and was slighted by the meanest servants.

[¶19.1] Having continued there some time, and not finding things to answer their expectations, nor profit to arise as they looked for, Captain Wollaston takes a great part of the servants, and transports them to Virginia, where he puts them off at good rates, selling their time to other men; and writes back to one Mr. Rassdall, one of his chief partners, and accounted their merchant, to bring another part of them to Virginia likewise, intending to put them of there as he had done the rest. And he, with the consent of the said Randall, appointed one Fitcher to be his Lieutenant, and govern the remains of the plantation, till he or Randall returned to take further order thereabout.

[¶19.6] But this Morton abovesaid, having more craft then honesty, (who had been a kind of pettifogger [cheap lawyer] of Furnival’s Inn [a London Inn of Chancery where lawyers associated],) in the other’s absence, watches an opportunity, (commons being but hard amongst them,) and got some strong drink and other junkets, and made them a feast; and after they were merry, he began to tell them, he would give them good counsel. “You see” (sayeth he) “that many of your fellows are carried to Virginia; and if you stay till this Randall return, you will also be carried away and sold for slaves with the rest. Therefore I would advise you to thrust out this Lieutenant Fitcher; and I, having a part in the plantation, will receive you as my partners and consociates; so may you be free from service, and we will converse, trade, plant, and live together as equals, and support and protect one another, or to like effects.” This counsel was easily received; so they took opportunity, and thrust Lieutenant Fitcher out of doors, and would suffer him to come no more amongst them, but forced him to seek bread to eat, and other relief from his neighbors, till he could get passage for England.

[¶19.7] After this they fell to great licentiousness [decadence], and led a dissolute life, pouring out themselves into all profaneness. And Morton became Lord of Misrule, and maintained (as it were) a school of Atheism. And after they had got some goods into their hands, and got much by trading with the Indians, they spent it as vainly, in quaffing and drinking both wine and strong waters in great excess and as some reported, 10 Pounds worth in a morning. They also set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women, for their consorts, dancing and frisking together, (like so many fairies, or furies rather,) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived and celebrated the feasts of the Roman Goddess Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians.

[¶19.8] Morton likewise (to spew his poetry) composed sundry rhymes and verses, some tending to lasciviousness [sensuality], and others to the detraction and scandal of some persons; which he affixed to this idle or idol May-Pole. They changed also the name of their place, and in stead of calling it Mount Wollaston, they call it Merry-Mount, as if this jollity would have lasted ever. But this continued not long, for after Morton was sent for England, (as follows to be declared,) shortly after came over that worthy gentleman, Mr. John Endicott, who brought over a patent under the broad seal of the government of the Massachusetts, who visiting those parts caused that May-Pole to be cut down, and rebuked them for their profaneness, and admonished them to look there should be better walking; so they now, or others, changed the name of their place again, and called it Mount Dagon. [Dagon = primary idol / god of the Philistines in the Bible]

[¶19.9] Now to maintain this riotous prodigality and profuse excess, Morton, thinking himself lawless, and hearing what gains the French and fisher-men made by trading of pieces [firearms], powder, and shot [ammunition] to the Indians, he, as the head of this consortship, began the practice of the same in these parts; and first he taught them how to use them, to charge, and discharge [their weapons], and what proportion of powder to give the piece, according to the size or bigness of the same; and what shot to use for fowls, and what for deer. And having thus instructed them [the Indians], he [Morton] employed some of them to hunt and fowl for him, so as they became far more active in that employment then any of the English, by reason of their swiftness of foot, and nimbleness of body, being also quick-sighted, and by continual exercise well knowing the haunts of all sorts of game. So as when they [the Indians] saw the execution that a piece [firearm] would do, and the benefits that might come by the same, they [the Indians] became mad, as it were, after them, and would not stick to give any prize they could attain to for them; accounting their bow and arrows but baubles in comparison of them.

[¶19.10] And here I may take occasion to bewail the mischief that this wicked man began in these parts, and which since base covetousness prevailing in men that should know better, has now at length got the upper hand, and made this thing common, notwithstanding any laws to the contrary; so as the Indians are full of pieces [firearms] all over, both fouling pieces, muskets, pistols, etc. They have also their moulds to make shot, of all sorts, as musket bullets, pistol bullets, swan and goose shot, and of smaller sorts; yea, some have seen them have their screw-plates to make scrupins themselves, when they want them, with sundry other implements, wherewith they are ordinarily better fitted and furnished than the English themselves.

[¶19.11] Yea, it is well known that they [the Indians] will have powder and shot, when the English want it, nor cannot get it; and that in a time of war or danger, as experience hath manifested, that when lead bath been scarce, and men for their own defense would gladly have given a groat a pound, which is dear enough, yet hath it here bought up and sent to other places, and sold to such as trade it with the Indians, at 12 pence the pound; and it is like they give three or four shillings to the pound, for they will have it at any rate. And these things have been done in the same times, when some of their neighbors and friends are daily killed by the Indians, or are in danger thereof, and live but at the Indians’ mercy. Yea, some [traders] (as they have acquainted them with all other things) have told them [the Indians] how gunpowder is made, and all the materials in it, and that they are to be had in their own land; and I am confident, could they attain to make saltpeter, they would teach them to make powder.

[¶19.12] 0h the horribleness of this villainy! how many both Dutch and English have been lately slain by those Indians, thus furnished; and no remedy provided, nay, the evil more increased, and the blood of their brethren sold for gains, as is to be feared; and in what danger all these colonies are in is too well known. Oh! that princes and parliaments would take some timely order to prevent this mischief; and at length to suppress it, by some exemplary punishments upon some of these gain-thirsty murderers, (for they deserve no better title,) before their colonies in these parts be overthrown by these barbarous savages, thus armed with their own weapons, by these evil instruments, and traitors to their neighbors and country.

[¶19.13] But I have forgot myself, and have been too long in this digression; but now to return. This Morton having thus taught them the use of pieces [firearms], he sold them all he could spare; and he and his consorts determined to send for many out of England, and had by some of the ships sent for above a score. The which being known, and his neighbors meeting the Indians in the woods armed with guns in this sorts, it was a terror unto them, who lived stragglingly, and were of no strength in any place. And other places (though more remote) saw this mischief would quietly spread over all, if not prevented. Besides, they saw they should keep no servants, for Morton would entertain any, how vile soever, and all the scum of the country, or any discontents, would flock to him from all places, if this nest was not broken; and they should stand in more fear of their lives and goods (in short time) from this wicked and debased crew, than from the savages themselves.

[¶19.14] So sundry of the chief of the straggling plantations, meeting together, agreed by mutual consent to solicit those of Plymouth (who were then of more strength then them all) to join with them, to prevent the further growth of this mischief, and suppress Morton and his consorts before they grew to further head and strength. Those that joined in this action (and after contributed to the charge of sending him for England) were from Pascataway, Namkeake, Vinisimett, Weesagascusett, Natasco, and other places whey any English were seated. Those of Plymouth being thus sought too by their messengers and letters, and weighing both their reasons, and the common danger, were willing to afford them their help; though themselves had least cause of fear or hurt.

[¶19.15] So, to be short, they first resolved jointly to write to him, and in a friendly and neighborly way to admonish him to forbear these courses, and sent a messenger with their letters to bring his answer. But he was so high as he scorned all advice, and asked who had to do with him; he had and would trade pieces [firearms] with the Indians in despite of all, with many other scurrilous terms full of disdain. They sent to him a second time, and bade him be better advised, and more temperate in his terms, for the country could not bear the injury he did; it was against their common safety, and against the king's proclamation. He answered in high terms as before, and that the king’s proclamation was no law; demanding what penalty was upon it. It was answered, more than he could bear his majesty’s displeasure.

[¶19.16] But insolently he persisted, and said the king was dead and his displeasure with him, and many the like things; and threatened withal that if any came to molest him, let them look to themselves, for he would prepare for them. Upon which they saw there was no way but to take him by force; and having so far proceeded, now to give over would make him far more haughty and insolent. So they mutually resolved to proceed, and obtained of the Governor of Plymouth to send Captain Standish, and some other aide with him, to take Morton by force. The which accordingly was done; but they found him to stand stiffly in his defense, having made fast his doors, armed his consorts, set diverse dishes of powder and bullets ready on the table; and if they had not been over-armed with drink, more hurt might have been done.

[¶19.17] They commanded him to yield, but he kept his house, and they could get nothing but stofes and scorns from him; but at length, fearing they would doe some violence to the house, he and some of his crew came out, but not to yield, but to shoot; but they were so steeled with drink as their pieces [firearms] were to heavy for them; himself with a carbine (over charged and almost half fild with powder and shot, as was after found) had thought to have shot Captain Standish; but he stepped to him, and put by his piece, and took him. Neither was there any hurt done to any of either side, save that one was so drunk that he ran his own nose upon the point of a sword that one held before him as he entered the house; but he lost but a little of his hot blood.

[¶19.18] Morton they brought away to Plymouth, where he was kept, till a ship went from the Isle of Shoals for England, with which he was sent to the Counsel of New England; and letters written to give them information of his course and carriage; and also one was sent at their common charge to inform their Honors more particularly, and to prosecute against him. But he fooled of the messenger, after he was gone from hence, and though he went for England, yet nothing was done to him, not so much as rebuked, for ought was heard; but returned the next year. Some of the worst of the company were dispersed, and some of the more modest kept the house till he should be heard from. But I have been too long about so unworthy a person, and bad a cause.

[¶19.19] This year Mr. Allerton brought over a young man for a minister to the people here, whether upon his own head, or at the motion of some friends there, I well know not, but it was without the church’s sending; for they had been so bitten by Mr. Lyford, as they desired to know the person well whom they should invite amongst them. His name was Mr. Rogers; but they perceived, upon some trial, that he was crazed in his brain; so they were fain to be at further charge to send him back again the next year, and lose all the charge that was expended in his hither bringing, which was not small by Mr. Allerton's account, in provisions, apparel, bedding, etc. After his return he grew quite distracted, and Mr. Allerton was much blamed that he would bring such a man over, they having charge enough otherwise. . . .