Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

-

Not a critical or scholarly text but a reading text for a seminar

-

Gratefully adapted from Heath Anthology online: http://college.cengage.com/english/lauter/heath/4e/students/author_pages/eighteenth/occommohegan_sa.html

-

Changes may include paragraph divisions, highlights, spelling updates, bracketed annotations, & elisions (marked by ellipses . . . )

|

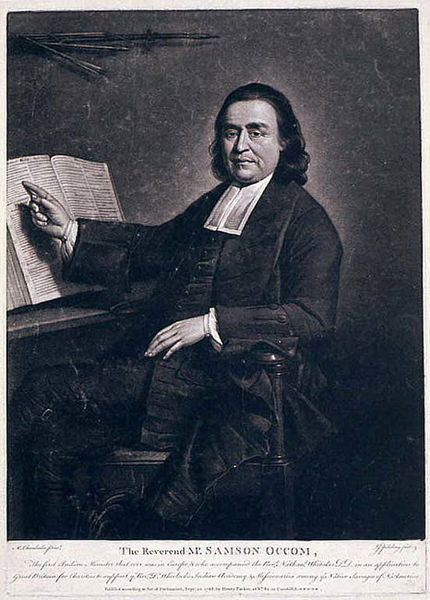

brief biography of

Samson Occom (1723-1792) see also Samson Occom,

A Short Narrative of My Life (1768) |

|

(1723-1792)

Born in a wigwam in 1723, Samson Occom was the son of

Joshua Tomacham and Sarah, reputed to be a descendant of the famous Mohegan

chief, Uncas (an ally of the Pilgrims whose fictional grandson is the title

character of James Fenimore Cooper's

The Last of the

Mohicans [1826]). In his autobiographical sketch,

A Short Narrative of My Life, dated September 17, 1768, Occom

described the nomadic existence led by his parents and their fellow Mohegans

during his youth.

At sixteen, missionaries to the Indians taught Samson the

basics of Christianity, and he

began to study English in order to read the scriptures. His conversion a year later increased his desire to read. In 1743,

twenty-year-old Occom went to study for four years with the Reverend Eleazar

Wheelock in Lebanon, Connecticut; Occom also studied with the Reverend

Solomon Williams in New London, CT. In 1749 he accepted the invitation of the Montauk

Indians of Long Island to become their schoolmaster. In 1751, he married

Mary Fowler (a Montauk Indian), who subsequently bore him ten children. To support

his rapidly growing family, Occom supplemented his stipend by working as a

farmer, fisherman, cooper, and bookbinder. His entire life was haunted by desperate financial circumstances.

Ordained in 1759, Occom spent the next year as an itinerant

minister in southern New England. In 1761, he became a missionary to the

Oneida Indians of the

Iroquois Confederacy. Determined to work among his own people, Occom moved his

family in 1764 to Mohegan, Connecticut (near New London) and assisted the

Reverend George Whitefield in

raising money for Wheelock’s Indian Charity School, which became present-day

Dartmouth College. Because of his success as a preacher and fund-raiser,

Whitefield sent him to Great Britain to raise money for the school. During

his two years there, Occom preached over three hundred sermons and raised

over 12,000 British Pounds Sterling.

After his return, Occom devoted his energies to preaching and working on

behalf of Native Americans. Prior to his tour of Great Britain, he had

helped the Mohegans try to settle their land claims. Now he became an

enthusiastic supporter of a plan formulated by his son-in-law, Joseph

Johnson (a Mohegan), to remove the Christian Indians of New England to lands

offered by the Oneida in western New York. The Revolutionary War halted this

move. In an address, Occom described the dangers of this war to his people.

Although he pointed out that the English sought to enslave the colonists,

Occom urged Indians not to become embroiled in the quarrels of white people

because he felt the war was the work of the devil.

Occom traveled throughout New England in 1784 to preach and raise funds for

resettlement of the Christian Indians onto Oneida lands, a cause that

absorbed him for the next six years. In 1789, he moved his own family to the

new Indian settlement called "Brothertown" or "Brotherton." He

spent his last years in continued service to his people, now beset by

controversies over land claims. Through his efforts, the Christian Indians

withstood Oneida efforts to reclaim their land and white schemes to lease the

Christian Indians’ land for far less than its worth. When he died in 1792 at

age sixty-nine, more than three hundred Indians attended his funeral. His

dream of a secure settlement for New England Indians was destined to fail,

as were all subsequent resettlements of Indians. After the War of 1812,

white encroachment caused the Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians to

purchase land from the Hochunk (Winnebago) and Menominee Indians in the

Green Bay area of what is now Wisconsin.

Occom published only two works:

A Sermon Preached by Samson Occom,...at

the Execution of Moses Paul (1772), the first Indian bestseller, and

Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1774). Undoubtedly, the success

of the sermon inspired Occom, a fine singer, to publish the collection.

For the first time after his English tour, Occom stepped into the public

limelight in 1771 when he preached the execution sermon for Moses Paul, a

fellow Christian Mohegan. Ejected from a Bethany tavern for drunkenness,

Paul killed the next person to leave—Moses Cook, a prominent citizen of

Waterbury, Connecticut. Granted a three-month reprieve by the General

Assembly of Connecticut, Paul wrote Occom on July 16, 1771, to ask that he

preach at the execution. Held on September 2, 1771, the execution drew a

large crowd. As New Haven’s first hanging in twenty years, it

offered a unique opportunity to hear a famous Indian minister preach at the

execution of a fellow tribesman. Whites and Native Americans flocked to the

event. Occom’s forceful and emotional sermon so moved his audience that he

was immediately urged to publish it. One of the few temperance sermons

published during that period, it achieved particular popularity because of

its application to Indians whose drunkenness whites feared.

Samson Occom Bridge, 1936, Connecticut