|

|

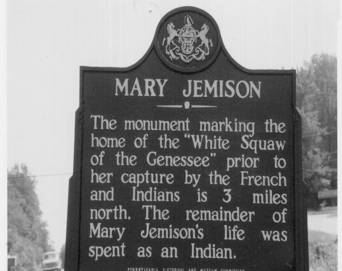

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

selections from NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF MRS. MARY JEMISON

from CHAPTER IX. |

|

[9.1]

Soon after the close of the revolutionary war, my Indian brother,

Kau-jises-tau-ge-au (which being interpreted signifies Black Coals,) offered me

my liberty, and told me that if it was

my choice I might go to my friends.

[that is, return to white settlements]

[9.2]

My son, Thomas, was anxious that I should go; and offered to go with me and

assist me on the journey . . . . But the Chiefs of our tribe, suspecting from

his appearance, actions, and a few warlike exploits, that Thomas would be a

great warrior, or a good counselor

[leader],

refused to let him leave them on any account whatever.

[9.3]

To go myself, and leave him, was more than I felt able to do; for he had been

kind to me, and was one on whom I placed great dependence. The Chiefs refusing

to let him go, was one reason for my

resolving to stay; but another, more powerful, if possible, was, that I had got

a large family of Indian children, that I must take with me; and that if I

should be so fortunate as to find my relatives, they would despise them, if not

myself; and treat us as enemies; or, at least with a degree of cold

indifference, which I thought I could not endure.

[9.4]

Accordingly, after I had duly considered the matter, I told my brother that it

was my choice to stay and spend the remainder of my days with my Indian friends,

and live with my family as I had heretofore done. He appeared well pleased with

my resolution, and informed me, that as

that was my choice, I should have a piece of land that I could call my own,

where I could live unmolested, and have something at my decease to leave for the

benefit of my children. . . .

[9.5]

I lived undisturbed, without hearing a word on the subject of my land, till the

great Council was held at Big Tree, in 1797, when Farmer's Brother, whose Indian

name is Ho-na-ye-wus, sent for me to attend the council. When I got there, he

told me that my brother had spoken to him to see that I had a piece of land

reserved for my use; and that then was the time for me to receive it.—He

requested that I would choose for myself and describe the bounds of a piece that

would suit me. I accordingly told him the place of beginning, and then went

round a tract that I judged would be sufficient for my purpose, (knowing that it

would include the Gardow Flats,) by stating certain bounds with which I was

acquainted.

[9.6]

When the Council was opened, and the business afforded a proper opportunity,

Farmer's Brother presented my claim, and rehearsed the request of my brother.

Red Jacket, whose Indian name is Sagu-yu-what-hah, . . . interpreted as

Keeper-awake, opposed me or my claim with all his influence and eloquence.

[<classic description of Indian oratory / politics]

Farmer's Brother insisted upon the

necessity, propriety and expediency of his proposition, and got the land

granted. The deed was made and signed, securing to me the title to all the land

I had described; under the same restrictions and regulations that other Indian

lands are subject to.

[9.7]

That land has ever since been known by the name of the Gardow Tract. . . .

[9.8]

My land derived its name, Gardow, from a hill that is within its limits, which

is called in the Seneca language Kau-tam. Kautam when interpreted signifies up

and down, or down and up, and is applied to a hill that you will ascend and

descend in passing it; or to a valley. . . .

[9.9]

About three hundred acres of my land, when I first saw it, was open flats

[level fields], lying

on the Genesee River, which it is supposed was cleared by

a race of inhabitants who preceded the

first Indian settlements in this part of the country. . . . It however was

and is believed by our people, that they were not Indians.

[9.10]

My flats were extremely fertile; but needed more labor than my daughters and

myself were able to perform

[agriculture remains women’s work, in contrast to much Euro-American

agriculture],

to produce a sufficient quantity of grain and other necessary productions of the

earth, for the consumption of our family. The land had lain uncultivated so long

that it was thickly covered with weeds of almost every description. In order

that we might live more easy, Mr. Parrish, with the consent of the chiefs, gave

me liberty to lease or my land to white people to till on shares. I accordingly

let it out, and have continued to do so, which makes my task less burthensome,

while at the same time I am more comfortably supplied with the means of support.

![]()