|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

selections from NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF MRS. MARY JEMISON

from CHAPTER VII. |

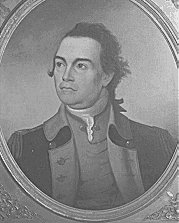

John Sullivan |

[7.1] For four or five years we sustained no loss in the war, except in the few who had been killed in distant battles; and our tribe, because of the remoteness of its situation, from the enemy, felt secure from an attack. At length, in the fall of 1779, intelligence was received that a large and powerful army of the rebels*, under the command of General Sullivan, was making rapid progress towards our settlement, burning and destroying the huts and corn-fields; killing the cattle, hogs and horses, and cutting down the fruit trees belonging to the Indians throughout the country. [*the American patriots opposing the British]

[7.2]

Our Indians immediately became alarmed . . . . But in order to prevent so great

a catastrophe, they sent out a few spies who were to . . . give information of

its advances and success.

[7.3]

Sullivan arrived at Canandaigua Lake, and had finished his work of destruction

there, and it was ascertained that he was about to march to our flats, when our

Indians resolved to give him battle on the way, and prevent, if possible, the

distresses to which they knew we should be subjected, if he should succeed in

reaching our town. Accordingly they sent all their women and children into the

woods . . . in order that we might make a good retreat if it should be necessary

. . . .

[7.4]

At length a scouting party from Sullivan's army arrived at the spot selected,

when the Indians arose from their ambush with all the fierceness and terror that

it was possible for them to exercise, and directly put the party upon a retreat.

Two Oneida Indians were all the prisoners that were taken in that skirmish. . .

.

[The two Indians and some American soldiers are killed.]

[7.5]

This tragedy being finished, our Indians again held a short council on the

expediency of giving Sullivan battle . . . and finally came to the conclusion

that they were not strong enough . . . : but that if it was possible they would

escape with their own lives, preserve their families, and leave their

possessions to be overrun by the invading army.

[7.6]

The women and children were then sent on still further towards Buffalo, . . .

accompanied by a part of the Indians, while the remainder secreted themselves in

the woods back of Beard's Town, to watch the movements of the army.

[7.7]

At that time I had three children who went with me on foot, one who rode on

horseback, and one whom I carried on my back.

[7.8]

Our corn was good that year; a part of which we had gathered and secured for

winter.

[7.9]

In one or two days . . . Sullivan and his army arrived at

[7.10]

. . . [W]e hunted continually till the Indians concluded that there could be no

risk in our once more taking possession of our lands. Accordingly we all

returned; but what were our feelings when we found that there was not a mouthful

of any kind of sustenance left, not even enough to keep a child one day from

perishing with hunger.

[7.11]

The weather by this time had become cold and stormy; and as we were destitute of

houses and food too, I immediately

resolved to take my children and look out for myself, without delay. With

this intention I took two of my little ones on my back, bade the other three

follow, and the same night arrived on the Gardow flats, where I have ever since

resided.

[7.12]

At that time, two negroes, who had run away from their masters sometime before,

were the only inhabitants of those flats. They lived in a small cabin and had

planted and raised a large field of corn, which they had not yet harvested. As

they were in want of help to secure their crop, I hired to them to husk corn

till the whole was harvested.

[7.13]

I have laughed a thousand times to myself when I have thought of the good old

negro, who hired me, who fearing that I should get taken or injured by the

Indians, stood by me constantly when I was husking, with a loaded gun in his

hand, in order to keep off the enemy, and thereby lost as much labor of his own

as he received from me, by paying good wages. I, however, was not displeased

with his attention; for I knew that I should need all the corn that I could earn

. . . .

[7.14]

This seasonable supply made my family comfortable for samp

[cornmeal mush]

and cakes through the succeeding winter, which was the most severe that I have

witnessed since my remembrance. The snow fell about five feet deep, and remained

so for a long time, and the weather was extremely cold; so much so indeed, that

almost all the game upon which the Indians depended for subsistence, perished,

and reduced them almost to a state of starvation through that and three or four

succeeding years. When the snow melted in the spring, deer were found dead upon

the ground in vast numbers; and other animals, of every description, perished

from the cold also, and were found dead, in multitudes. Many of our people

barely escaped with their lives, and some actually died of hunger and freezing.

[7.15]

But to return from this digression: Having been completely routed at Little

Beard's Town, deprived of a house, and without the means of building one in

season, after I had finished my husking, and having found from the short

acquaintance which I had had with the negroes, that they were kind and friendly,

I concluded, at their request, to take up my residence with them for a while in

their cabin, till I should be able to provide a hut for myself. I lived more

comfortable than I expected to through the winter, and the next season made a

shelter for myself.

[7.16]

The negroes continued on my flats two or three years after this, and then left

them for a place that they expected would suit them much better. But as that

land became my own in a few years, by virtue of a deed from the Chiefs of the

Six Nations

[Iroquois Confederacy],

I have lived there from that to the present time.

[7.17]

My flats

[fields]

were cleared before I saw them; and it was the opinion of the oldest Indians

that were at Genishau, at the time that I first went there, that all the flats

on the

[7.18]

The next summer after Sullivan's campaign, our Indians, highly incensed at the

whites for the treatment they had received, and the sufferings which they had

consequently endured, determined to obtain some redress by destroying their

frontier settlements. Corn Planter,

otherwise called John O'Bail, led the Indians, and an officer by the name of

[7.19]

In that expedition, when they came to Fort Plain, on the Mohawk river, Corn

Planter and a party of his Indians took old John O'Bail, a white man, and made

him a prisoner. Old John O'Bail, in his younger days had frequently passed

through the Indian settlements that lay between the

[7.20]

Corn Planter, was a chief of considerable eminence;

and having been informed of his parentage and of the place of his father's

residence, took the old man at this time, in order that he might make an

introduction leisurely, and become acquainted with a man to whom, though a

stranger, he was satisfied that he owed his existence.

[7.21]

After he had taken the old man, his father, he led him as a prisoner ten or

twelve miles up the river, and then stepped before him, faced about, and

addressed him in the following terms:—

[7.22]

"My name is John O'Bail, commonly called Corn Planter. I am your son! you are my

father!

You are now my prisoner, and subject to the customs of Indian warfare: but you

shall not be harmed; you need not fear. . . . I am your son! I am a warrior! I

was anxious to see you, and to greet you in friendship. I went to your cabin and

took you by force! But your life shall be spared. Indians love their friends and

their kindred, and treat them with kindness. If now you choose to follow the

fortune of your yellow son, and to live with our people, I will cherish your old

age with plenty of venison

[deer meat],

and you shall live easy: But if it is your choice to return to your fields and

live with your white children, I will send a party of my trusty young men to

conduct you back in safety. I respect you, my father; you have been friendly to

Indians, and they are your friends."

[7.23]

Old John chose to return. Corn Planter, as good as his word, ordered an escort

to attend him home, which they did with the greatest care. . . .

![]()

Cornplanter (1730s-1836)

painting by F. Bartoli, 1796