|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

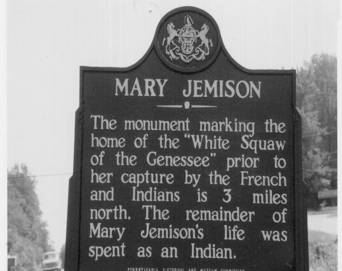

selections from NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF MRS. MARY JEMISON

from CHAPTER XVI. |

|

[16.1]

. . . I have never once been sick till within a year or two, only as I have

related. Spirits and tobacco I have never used, and I have never once attended

an Indian frolic

[drinking party?].

When I was taken prisoner, and for sometime after that, spirits was not known;

and when it was first introduced, it was in small quantities, and used only by

the Indians; so that it was a long time before the Indian women begun to even

taste it.

[16.2]

After the French war, for a number of years, it was the practice of the Indians

of our tribe to send to Niagara and get two or three kegs of rum, (in all six or

eight gallons,) and hold a frolic as long as it lasted. When the rum was brought

to the town, all the Indians collected, and before a drop was drank, gave all

their knives, tomahawks, guns, and other instruments of war, to one Indian,

whose business it was to bury them in a private place, keep them concealed, and

remain perfectly sober till the frolic was ended. Having thus divested

themselves, they commenced drinking, and continued their frolic till every drop

was consumed, If any of them became quarrelsome, or got to fighting, those who

were sober enough bound them upon the ground, where they were obliged to lie

till they got sober, and then were unbound. When the fumes of the spirits had

left the company, the sober Indian returned to each the instruments with which

they had entrusted him, and all went home satisfied. A frolic of that kind was

held but once a year, and that at the time the Indians quit their hunting, and

come in with their deer-skins.

[16.3]

In those frolics the women never participated. Soon after the revolutionary war,

however, spirits

[alcohol]

became common in our tribe, and has been used indiscriminately by both sexes;

though there are not so frequent instances of intoxication amongst the squaws as

amongst the Indians.

[16.4]

To the introduction and use or that baneful article

[alcohol],

which has made such devastation in our tribes, and threatens the extinction of

our people, (the Indians,) I can with the greatest propriety impute

[attribute] the whole of

my misfortune in losing my three sons. But as I have before observed, not even

the love of life will restrain an Indian from sipping the poison that he knows

will destroy him. The voice of nature, the rebukes of reason, the advice of

parents, the expostulations of friends, and the numerous instances of sudden

death, are all insufficient to reclaim an Indian, who has once experienced the

exhilarating and inebriating effects of spirits, from seeking his grave in the

bottom of his bottle!

[16.5]

My strength has been great for a woman of my size . . . . I have planted, hoed,

and harvested corn every season but one since I was taken prisoner. Even this

present fall (1823) I have husked my corn and backed it into the house.

[16.6]

The first cow that I ever owned, I bought of a squaw sometime after the

revolution. It had been stolen from the enemy. . . .

[16.7]

. . . It was believed for a long time,

by some of our people, that I was a great witch; but they were unable to prove

my guilt, and consequently I escaped the certain doom of those who are convicted

of that crime, which, by Indians, is considered as heinous as murder. Some of my

children had light brown hair, and tolerable fair skin, which used to make some

say that I stole them . . . .

[16.8]

I have been the mother of eight children; three of whom are now living, and I

have at this time thirty-nine grand children, and fourteen great-grand children,

all living in the neighborhood of Genesee River, and at Buffalo.

[16.9]

I live in my own house, and on my own land with my youngest daughter, Polly,

who is married to George Chongo, and has three children.

[16.10]

My daughter Nancy, who is married to Billy Green, lives about 80 rods

[400 yards]

south of my house, and has seven children.

[16.11]

My other, daughter, Betsey, is married to John Green, has seven children, and

resides 80 rods north of my house.

[16.12]

Thus situated in the midst of my children, I expect I shall soon leave the

world, and make room for the rising generation. . . . If my family will live

happily, and I can be exempted from trouble while I have to stay, I feel as

though I could lay down in peace a life that has been checked in almost every

hour, with troubles of a deeper dye, than are commonly experienced by mortals.

END of selections from Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison

![]()