|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

selections from NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF MRS. MARY JEMISON

from CHAPTER X.

|

|

[10.1]

. . . Few mothers, perhaps, have had less trouble with their children during

their minority

[childhood]

than myself. In general, my children were friendly to each other,

and it was very seldom that I knew them to have the least difference or quarrel

. . . .

[10.2]

My happiness in this respect, however, was not without alloy

[taint];

for my son Thomas, from some cause

unknown to me, from the time he was a small lad, always called his brother John,

a witch, which was the cause, as they grew towards manhood, of frequent and

severe quarrels between them, and gave me much trouble and anxiety for their

safety. After Thomas and John arrived to manhood, in addition to the former

charge, John got two wives, with whom he

lived till the time of his death. Although polygamy was tolerated in our tribe,

Thomas considered it a violation of good and wholesome rules in society . .

. . Consequently, he frequently reprimanded John . . . and, as he never could

reconcile himself to it, he was frequently, almost constantly, when they were

together, talking to him on the same subject. John always resented such

reprimand, and reproof, with a great degree of passion, though

they never quarreled, unless Thomas was

intoxicated.

[10.3]

In his fits of drunkenness, Thomas seemed to lose all his natural reason,

and to conduct like a wild or crazy man,

without regard to relatives, decency or propriety. At such times he often

threatened to take my life for having raised a witch, (as he called John,)

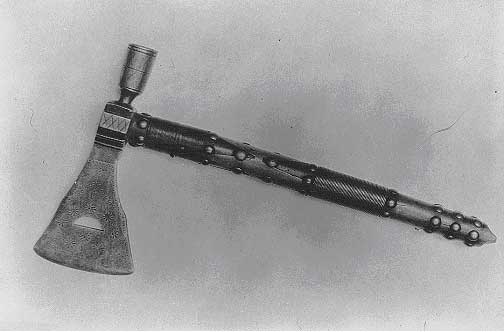

and has gone so far as to raise his tomahawk to split my head. He, however,

never struck me . . . .

[10.4]

. . . No one can conceive of the constant trouble that I daily endured on their

account—on the account of my two oldest sons, whom I loved equally . . . .

[10.5]

My advice and expostulations with my sons were abortive; and year after year

their disaffection for each other increased. At length, Thomas came to my house

on the 1st day of July, 1811, in my absence, somewhat intoxicated, where he

found John, with whom he immediately commenced a quarrel on their old subjects

of difference.— . . . He caught Thomas by the hair of his head, dragged him out

at the door and there killed him, by a blow which he gave him on the head with

his tomahawk!

[10.6]

I returned soon after, and found my son lifeless at the door, on the spot where

he was killed! No one can judge of my feelings on seeing this mournful

spectacle; and what greatly added to my distress, was the fact that he had

fallen by the murderous hand of his brother! . . .

[10.7]

As soon as I had recovered a little from the shock which I felt at the sight of

my departed son, and some of my neighbors had come in to assist in taking care

of the corpse, I hired Shanks, an Indian, to go to Buffalo, and carry the

sorrowful news of Thomas' death, to our friends at that place, and request the

Chiefs to hold a Council, and dispose of John as they should think proper.

Shanks set out on his errand immediately,—and John, fearing that he should be

apprehended and punished for the crime he had committed, at the same time went

off towards Caneadea.

[10.8]

Thomas was decently interred in a style corresponding with his rank.

[10.9]

The Chiefs soon assembled in council on the trial of John, and after having

seriously examined the matter according to their laws, justified his conduct,

and acquitted him. They considered Thomas to have been the first transgressor,

and that for the abuses which he had offered, he had merited from John the

treatment that he had received.

[10.10]

John, on learning the decision of the council, returned to his family. . . .

[10.11]

Thomas had four wives, by whom he had eight children. Jacob Jemison, his second

son by his last wife, who is at this time twenty-seven or twenty-eight years of

age, went to Dartmouth college, in the

spring of 1816, for the purpose of receiving a good education, where it was said

that he was an industrious scholar, and made great proficiency in the study

of the different branches to which he attended. Having spent two years at that

Institution, he returned in the winter of 1818, and is now at

[10.12]

Thomas, at the time he was killed, was a few moons over fifty-two years old, and

John was forty-eight. As he

[Thomas]

was naturally good natured, and possessed a friendly disposition, he would not

have come to so untimely an end, had it not been far his intemperance

[drunkenness].

He fell a victim to the use of ardent spirits

[alcohol]—a

poison that will soon exterminate the Indian tribes in this part of the country,

and leave their names without a root or branch. . . .

![]()