|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

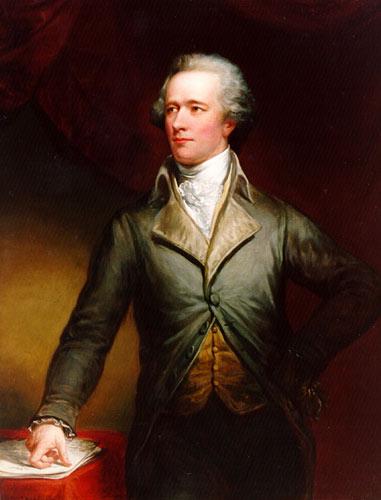

Selections from The Federalist (a.k.a. The Federalist Papers) 1787-88 Federalist # 9: The by Alexander Hamilton |

|

[9.1] A

firm

[9.2] From the

disorders that disfigure the annals

[historical records]

of those republics

the advocates of despotism

[tyranny or authoritarian government]

have drawn

arguments, not only against the forms of

republican government, but against the very principles of civil liberty

[human

rights].

They have decried all free government as

inconsistent with the order of society, and have indulged themselves in

malicious exultation over its friends and partisans. Happily for mankind,

stupendous fabrics [awesome structures or

frameworks] reared on the

basis of liberty, which have flourished for ages, have, in a few glorious

instances, refuted their gloomy sophisms [flawed

arguments]. And, I

trust,

[9.3] But it is not to be denied that the

portraits they have sketched of republican government were too just copies

[painfully accurate accounts]

of the originals

[actual histories]

from which they were taken. If

it had been found impracticable to have devised models of a more perfect

structure, the enlightened friends to liberty would have been obliged to abandon

the cause of that species of government [a

republic] as

indefensible. The science of politics,

however, like most other sciences, has received great improvement.

The efficacy of

various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all,

or imperfectly known to the ancients. [<Enlightenment

principles aren’t utopian or

perfectionist, but they do admit the possibility of progress; classical models

are meant to be improved on, not slavishly copied.]

The regular distribution

of power into distinct departments; the introduction of legislative

balances and checks; the institution

of courts composed of judges holding

their offices during good behavior; the

representation of the people in the

legislature by deputies of their own election: these are wholly new discoveries,

or have made their principal progress towards perfection in modern times.

They are means, and powerful means, by which

the excellences of republican government

may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided. To this catalogue

of circumstances that tend to the amelioration of popular systems of civil

government, I shall venture, however novel it may appear to some, to

add one more, on a principle which

has been made the foundation of an objection to the new Constitution; I mean

the

enlargement of the

orbit

within which such systems are to revolve,

[<astronomical metaphor; cf. Thomas Paine,

The Age of Reason]

either in respect to the

dimensions of a single State or to the

consolidation of several smaller States into one great Confederacy. . . .

[9.4] The utility of a Confederacy, as well

to suppress faction [division]

and to guard the internal

tranquility of States, as to increase their external force and security, is in

reality not a new idea. It has been practiced upon in different countries and

ages, and has received the sanction of the most approved writers on the subject

of politics. The opponents of the plan

proposed have, with great assiduity, cited and circulated the observations of

Montesquieu [French political thinker,

1689-1755]

on the necessity of a contracted

[limited]

territory for a republican

government. But they

seem not to have been apprised of the sentiments of that great man expressed in

another part of his work . . . .

[9.5] When Montesquieu recommends a small extent for

republics, the standards he had in view were of dimensions far short of the

limits of almost every one of these States. Neither

[9.6] A distinction, more subtle than accurate, has been

raised

between a

confederacy and a

consolidation

of the States. The essential characteristic of

the first [confederacy]

is said to be, the

restriction of its authority to the

members in their collective capacities, without reaching to the individuals

of whom they are composed. It is contended that the national council ought to

have no concern with any object of internal administration. An exact equality of

suffrage between the members has also been insisted upon as a leading feature of

a confederate government. [<as in the

pre-1900s U.S. Senate]

. . .

[9.7] The definition of a

confederate republic

seems simply to be "an assemblage of societies,''

or an association of two or more states into one state. The extent,

modifications, and objects of the federal authority are mere matters of

discretion. So long as the separate organization of the members be not

abolished; so long as it exists, by a constitutional necessity, for local

purposes; though it should be in perfect

subordination to the general authority of the union, it would still be, in fact

and in theory, an association of states, or a confederacy. The proposed

Constitution, so far from implying an abolition of the State governments, makes

them constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct

representation in the Senate, and leaves in their possession certain exclusive

and very important portions of sovereign power.

[<retention of “states’

rights” in federal union]

This fully corresponds, in every rational import

of the terms, with the idea of a federal government. . . .

PUBLIUS.

Hamilton,

award-winning 2014-16 musical

based on 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton

by Ron Chernow

Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), first secretary of Treasury