|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

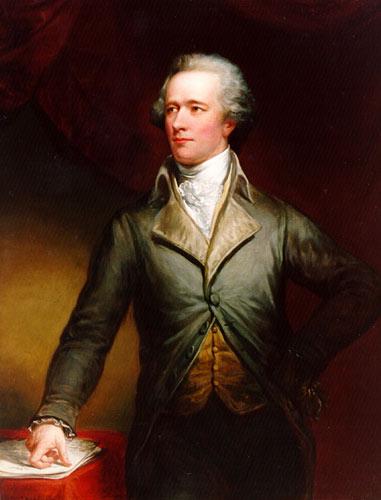

Selections from The Federalist (a.k.a. The Federalist Papers) 1787-88 Federalist # 6: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States by Alexander Hamilton |

|

[6.1]

.

. . A man must be far gone in

Utopian speculations who can

seriously doubt that, if these States should either be wholly disunited, or only

united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be

thrown would have frequent and violent contests

[controversies, combats]

with each other.

To presume a want of motives for such

contests as an argument against their existence, would be to forget that men are

ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious. [Enlightenment

skepticism re human motives]

To look for a continuation of

harmony between a number of independent, unconnected sovereignties in the same

neighborhood, would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to

set at defiance the accumulated experience of ages.

[Enlightenment

appeal to empirical and historical evidence;

[6.2] To multiply examples of the agency of personal

considerations in the production of great national events, either foreign or

domestic, according to their direction, would be an unnecessary waste of time. .

. . Perhaps, however, a reference, tending to illustrate the general principle,

may with propriety be made to a case which has lately happened among ourselves.

If Shays had not been a

desperate debtor,

it is much to be doubted whether

[6.3] But notwithstanding the concurring testimony of

experience, in this particular, there are still to be found visionary or

designing men [cf. “Utopian speculations” above,

6.1], who stand

ready to advocate the paradox of perpetual peace between the States, though

dismembered and alienated from each other.

The genius of

republics (say they) is pacific; the spirit of commerce has a tendency to soften

the manners of men, and to extinguish those inflammable humors which have so

often kindled into wars. Commercial republics, like ours, will never be disposed

to waste themselves in ruinous contentions with each other. They will be

governed by mutual interest, and

will cultivate a spirit of mutual amity and concord.

[6.4] [<after stating his opponents case,

[6.6] In the government of

[6.7] There have been, if I may so express it, almost as

many popular as royal wars.

The cries of the nation [its people]

and the importunities

[insistent demands]

of their representatives

have, upon various occasions, dragged their monarchs into war, or continued them

in it, contrary to their inclinations, and sometimes contrary to the real

interests of the State. . . .

[6.8] The wars of these two last-mentioned nations

[Austria & Bourbon France]

have in a great measure grown

out of commercial considerations,--the desire of supplanting and the fear of

being supplanted, either in particular branches of traffic or in the general

advantages of trade and navigation.

[6.9] From this summary of what has taken place in other

countries, whose situations have borne the nearest resemblance to our own, what

reason can we have to confide in those reveries

[cf. “Utopian speculations,” 6.1]

which would seduce us into an expectation of peace and

cordiality between the members of the present confederacy, in a state of

separation? Have we not already seen enough of the fallacy and extravagance of

those idle theories which have amused us with promises of an exemption from the

imperfections, weaknesses and evils incident to society in every shape?

Is it not time to awake from the

deceitful dream of a golden age [Enlightenment

reaction against imagination over reason],

and to adopt as a practical maxim for

the direction of our political conduct that we, as well as the other inhabitants

of the globe, are yet remote from the happy empire of perfect wisdom and perfect

virtue? [human perfectability is not

part of the Enlightenment or

the

Constitution

(which advances "a more perfect

union" but not a "perfect union." Rather, the

Enlightenment & the Constitution admit human imperfection and irrationality, and

attempt to restrain or balance such qualities against humanity's virtues.]

. . .

PUBLIUS.