|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

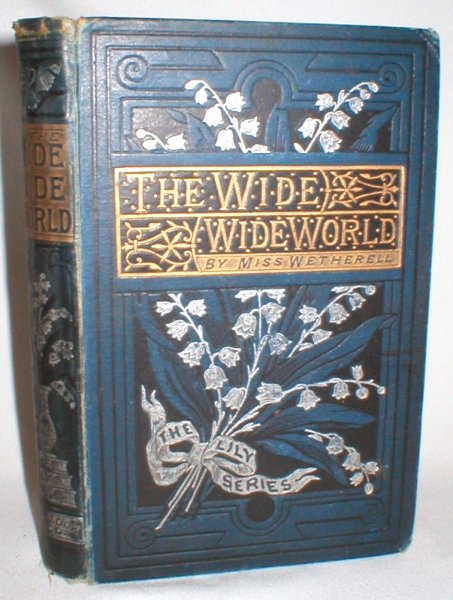

Susan B. Warner The Wide, Wide World

Chapter 11

|

|

CHAPTER XI.

Downward,

and ever farther,

And ever the

brook beside;

And ever fresher

murmured,

And ever clearer, the

tide.—LONGFELLOW. From the German.

[11.1]

Clouds and rain

and cold winds kept Ellen within doors for several days. This did not better

[improve]

the state of

matters between herself and her aunt. Shut up with her in the kitchen from

morning till night, with the only variety the old lady's company part of the

time, Ellen thought neither of them improved upon acquaintance. Perhaps they

thought the same of her; she was certainly not in her best mood. With nothing to

do, the time hanging very heavy on her hands,

disappointed, unhappy, frequently

irritated, Ellen became at length very ready to take offence, and nowise

disposed to pass it over or smooth it away. She seldom showed this in words,

it is true, but it rankled in her mind. Listless and brooding, she sat day after

day, comparing the present with the past, wishing vain wishes, indulging

bootless regrets, and looking upon her aunt and grandmother with an eye of more

settled aversion. The only other person she saw was Mr. Van Brunt, who came in

regularly to meals; but he never said anything unless in answer to Miss

Fortune's questions and remarks about the farm concerns. These did not interest

her; and she was greatly wearied with the sameness of her life. She longed to go

out again; but Thursday, and Friday, and Saturday, and Sunday passed, and the

weather still kept her close prisoner. Monday brought a change, but though a

cool, drying wind blew all day, the ground was too wet to venture out.

[11.2]

On the

evening of that day, as Miss Fortune was setting the table for tea, and Ellen

sitting before the fire, feeling weary of everything,

the kitchen door opened, and a girl

somewhat larger and older than herself came in. She had a pitcher in her

hand, and marching straight up to the tea-table, she said,

[11.3]

"Will you let granny have a little milk tonight, Miss

Fortune? I can't find the cow. I'll bring it back tomorrow."

[11.4]

"You ha'n't

lost her,

[11.5]

"Have, though," said the other; "she's been away these two

days."

[11.6]

"Why didn't you go somewhere nearer for milk?"

[11.7]

"Oh! I don't know—I guess your'n is the sweetest," said the

girl, with a look Ellen did not understand.

[11.8]

Miss Fortune

took the pitcher and went into the pantry. While she was gone, the two children

improved the time in looking very hard at each other.

Ellen's gaze was modest enough, though it

showed a great deal of interest in the new object; but the broad, searching

stare of the other seemed intended to take in all there was of Ellen from her

head to her feet, and keep it, and find out what sort of a creature she was at

once. Ellen almost shrank from the bold black eyes but they never wavered,

till Miss Fortune's voice broke the spell.

[11.9]

"How's your grandmother, Nancy?"

[11.10]

"She's tolerable, ma'am, thank you."

[11.11]

"Now if you don't bring it back tomorrow, you won't get any

more in a hurry," said Miss Fortune, as she handed the pitcher back to the girl.

[11.12]

"I'll mind it," said the latter, with a little nod of her

head, which seemed to say there was no danger of her forgetting.

[11.13]

"Who is that, aunt Fortune?" said Ellen, when she was gone.

[11.14]

"She is a girl that lives up on the mountain yonder."

[11.15]

"But what's her name?"

[11.16]

"I had just as

lief

[prefer] you wouldn't know

her name. She ain't a good girl. Don't you never have

anything to do with her."

[11.17]

Ellen was in no mind to give credit to all her aunt's

opinions, and she set this down as in part at least coming from ill-humor.

[11.18]

The next

morning was calm and fine, and Ellen spent nearly the whole of it out of doors.

She did not venture near the ditch, but in every other direction she explored

the ground, and examined what stood or grew upon it as thoroughly as she dared.

Toward noon she was standing by the little gate at the back of the house,

unwilling to go in, but not knowing what more to do, when

Mr. Van Brunt came

from the lane with a load of wood. Ellen watched the oxen toiling up the ascent,

and thought it looked like very hard work; she was sorry for them.

[11.19]

"Isn't that a very heavy load?" she

asked of their driver, as he was throwing it down under the apple-tree.

[11.20]

"Heavy? Not a bit of it. It ain't

nothing at all to 'em. They'd take twice as much any day with pleasure."

[11.21]

"I shouldn't think so," said Ellen;

"they don't look as if there was much pleasure about it. What makes them lean

over so against each other when they are coming up hill?"

[11.22]

"Oh, that's just a way they've got.

They're so fond of each other, I suppose.

Perhaps they've something particular to say, and want to put their heads

together for the purpose."

[11.23]

"No," said Ellen, half-laughing, "it can't be that; they

wouldn't take the very hardest time for that; they would wait till they got to

the top of the hill; but there they stand just as if they were asleep, only

their eyes are open. Poor things!"

[11.24]

"They're not very poor any how," said Mr. Van Brunt; "there

ain't a finer yoke of oxen to be seen than them are, nor in better condition."

[11.25]

He went on throwing the wood out of the cart, and Ellen stood

looking at him.

[11.26]

"What'll you give me if I'll make you a scup one of these

days?" said Mr. Van Brunt.

[11.27]

"A scup?" said Ellen.

[11.28]

"Yes—a scup! How would you like it?"

[11.29]

"I don't know what it is." said Ellen.

[11.30]

"A scup!—May be you don't know it by that name; some folks

call it a swing."

[11.31]

"A swing! Oh, yes," said Ellen, "now I know. Oh, I like it

very much."

[11.32]

"Would you like to have one?"

[11.33]

"Yes, indeed I should, very much."

[11.34]

"Well, what'll you give me, if I'll fix you one?"

[11.35]

"I don't know," said Ellen, "I have nothing to give; I'll be

very much obliged to you, indeed."

[11.36]

"Well now,

come, I'll make a bargain with you; I'll engage to fix up a scup for you,

if you'll give me a kiss."

[11.37]

Poor Ellen

was struck dumb. The good-natured Dutchman had taken a fancy to the little

pale-faced, sad-looking stranger, and really felt very kindly disposed toward

her, but she neither knew, nor at the moment cared about that. She stood

motionless,

utterly astounded at his

unheard-of proposal, and not a little indignant; but when, with a good-natured

smile upon his round face, he came near to claim the kiss he no doubt thought

himself sure of, Ellen shot from him like an arrow from a bow. She rushed to

the house, and bursting open the door, stood with flushed face and sparkling

eyes in the presence of her

astonished aunt.

[11.38]

"What in the world is the matter?"

exclaimed that lady.

[11.39]

"He wanted to kiss me!"

said Ellen, scarce knowing whom she was talking to, and crimsoning more and

more.

[11.40]

"Who wanted to kiss you?"

[11.41]

"That man out there."

[11.42]

"What man?"

[11.43]

"The man that drives the oxen."

[11.44]

"What, Mr. Van Brunt?" And Ellen never forgot the loud ha!

ha! which burst from Miss Fortune's wide-open mouth. "Well, why didn't you let

him kiss you?"

[11.45]

The laugh, the look, the tone, stung

Ellen to the very quick.

In a fury of passion she dashed away out of the kitchen, and up to her own room.

And there, for a while,

the storm of

anger drove over her with such violence that conscience had hardly time to

whisper. Sorrow came in again as passion faded, and gentler but very bitter

weeping took the place of compulsive sobs of rage and mortification, and then

the whispers of conscience began to be heard a little. "Oh, mamma! mamma!" cried

poor Ellen in her heart, "how miserable I am without you! I never can like aunt

Fortune—it's of no use—I never can like her; I hope I shan't get to hate

her!—and that isn't right.

I am

forgetting all that is good and there's nobody to put me in mind. Oh, mamma!

if I could lay my head in your lap for a minute!" Then came thoughts of her

Bible and hymn-book, and the friend who had given it; sorrowful thoughts they

were; and at last, humbled and sad, poor

Ellen sought that great friend she knew she had

displeased, and prayed earnestly to be made a good child; she felt and owned she

was not one now.

[11.46]

It was long after mid-day when Ellen

rose from her knees. Her passion was all gone; she felt more gentle and pleasant

than she had done for days; but at the bottom of her heart resentment was not

all gone. She still

thought she had cause to be angry, and she could not think of her aunt's look

and tone without a thrill of painful feeling. In a very different mood, however,

from that in which she had flown up stairs two or three hours before, she now

came softly down, and went out by the front door, to avoid meeting her aunt. She

had visited that morning a little brook, which ran through the meadow on the

other side of the road. It had great charms for her; and now crossing the lane

and creeping under the fence, she made her way again to its banks. At a

particular spot, where the brook made one of its sudden turns, Ellen sat down

upon the grass, and watched the dark water,—whirling, brawling over the stones,

hurrying past her, with ever the same soft pleasant sound, and she was never

tired of it. She did not hear

footsteps

drawing near, and it was not till some one was close beside her, and a voice

spoke almost in her ears, that she raised her startled eyes and saw

the little girl who

had come the evening before for a pitcher of milk.

[11.47]

"What are you doing?" said the latter.

[11.48]

"I'm watching for fish," said Ellen.

[11.49]

"Watching for fish!" said the other, rather disdainfully.

[11.50]

"Yes," said Ellen,—"there, in that little quiet place they

come sometimes; I've seen two."

[11.51]

"You can look for fish another time.

Come now and take a walk with me."

[11.52]

"Where?" said Ellen.

[11.53]

"Oh, you shall see. Come! I'll take you all about and show

you where people live; you ha'nt been anywhere yet, have you?"

[11.54]

"No," said Ellen,—"and I should like dearly to go, but—"

[11.55]

She

hesitated. Her aunt's words came to mind, that this was not a good girl, and

that she must have nothing to do with her; but she had not more than

half-believed them, and she could not possibly bring herself now to go in and

ask Miss Fortune's leave to take this walk. "I am sure," thought Ellen, "she

would refuse me if there was no reason in the world."

And then the delight

of rambling though the beautiful country, and being for awhile in other company

than that of her aunt Fortune and the old grandmother! The temptation was too

great to be withstood.

[11.56]

"Well, what are you thinking about?" said the girl; "what's

the matter? won't you come?"

[11.57]

"Yes," said Ellen, "I'm ready. Which way shall we go?"

[11.58]

With the

assurance from the other that she would show her plenty of ways, they set off

down the lane; Ellen with a secret fear of being seen and called back, till they

had gone some distance, and the house was hid from view. Then her pleasure

became great. The afternoon was fair and mild, the footing pleasant, and

Ellen felt like a bird out of a cage. She was ready to be delighted

with every trifle; her companion could not by any means understand or enter into

her bursts of pleasure at many a little thing which she of the black eyes

thought not worthy of notice. She tried to bring Ellen back to higher subjects

of conversation.

[11.59]

"How long have you been here?" she asked.

[11.60]

"Oh, a good while," said Ellen,—"I don't know exactly; it's a

week I believe."

[11.61]

"Why, do you call that a good while?" said the other.

[11.62]

"Well, it seems a good while to me," said Ellen, sighing; "it

seems as long as four, I am sure."

[11.63]

"Then you don't like to live here much, do you?"

[11.64]

"I had rather be at home, of course."

[11.65]

"How do you like your aunt Fortune?"

[11.66]

"How do I like her?" said Ellen, hesitating,—"I think she's

good-looking, and very smart."

[11.67]

"Yes, you

needn't tell me she's smart,—everybody knows that; that ain't what I ask

you;—how do you like

her?"

[11.68]

"How do I like her?" said Ellen, hesitating,—"how can I tell

how I shall like her? I haven't lived with her but a week yet."

[11.69]

"You might

just as well ha' spoke out," said the other, somewhat scornfully;—"do you think I don't know you half-hate her already? and it'll be

whole hating in another week more. When I first heard you'd come, I guessed

you'd have a sweet time with her."

[11.70]

"Why?" said Ellen.

[11.71]

"Oh, don't

ask me why," said the other, impatiently, "when you know as well as I do.

Every soul that speaks of you says 'poor

child' and 'I'm glad I ain't her.' You needn't try to come cunning over me.

I shall be too much for you, I tell you."

[11.72]

"I don't know what you mean," said Ellen.

[11.73]

"Oh, no, I suppose you don't," said the other in the same

tone,—"of course you don't; I suppose you don't know whether your tongue is your

own or somebody's else. You think Miss Fortune is an angel, and so do I; to be

sure she is!"

[11.74]

Not very pleased with this kind of talk, Ellen walked on for

a while in grave silence. Her companion mean time recollected herself; when she

spoke again it was with an altered tone.

[11.75]

"How do you like Mr. Van Brunt?"

[11.76]

"I don't like him at all," said Ellen,

reddening.

[11.77]

"Don't you!" said the other

surprised,—"why everybody likes him. What don't you like him for?"

[11.78]

"I don't like him," repeated Ellen.

[11.79]

"Ain't Miss Fortune queer to live in

the way she does?"

[11.80]

"What way?" said Ellen.

[11.81]

"Why, without any help,—doing all her

own work, and living all alone, when she's so rich as she is."

[11.82]

"Is she rich?" asked Ellen.

[11.83]

"Rich! I

guess she is! she's

one of the very best farms in the country, and money enough

to have a dozen help, if she wanted 'em. Van Brunt takes care of the farm, you

know?"

[11.84]

"Does he?" said Ellen.

[11.85]

"Why, yes, of course he does; didn't you know that? what did

you think he was at your house all the time for?"

[11.86]

"I am sure I don't know," said Ellen. "And are those aunt

Fortune's oxen that he drives?"

[11.87]

"To be sure

they are. Well, I do think you are

green, to have been there all this time, and not found that out.

Mr. Van Brunt does just what he pleases

over the whole farm though; hires what help he wants, manages everything; and

then he has his share of all that comes off it. I tell you what—you'd better

make friends with Van Brunt, for if any body can help you when your aunt

gets one of her ugly fits, it's him; she don't care to meddle with him much."

[11.88]

Leaving the

lane, the two girls took a foot-path leading across the fields. The stranger was

greatly amused here with

Ellen's

awkwardness in climbing fences. Where it was a possible thing, she was fain

to crawl under; but one or twice that could not be done, and having with

infinite difficulty mounted to the top rail, poor Ellen sat there in a most

tottering condition, uncertain on which side of the fence she should tumble

over, but seeing no other possible way of getting down. The more she trembled

the more her companion laughed, standing aloof

[proudly distant]

meanwhile, and insisting she

should get down by herself. Necessity enabled her to do this at last, and each

time the task became easier; but

Ellen secretly made up her mind that her new friend was not

likely to prove a very good one.

[11.89]

As they went

along, she pointed out to Ellen two or three houses in the distance, and gave

her not a little

gossip about the

people who lived in them; but all this Ellen scarcely heard, and cared nothing

at all about. She had paused by the side of

a large rock

standing alone by the wayside, and was looking very closely at its surface.

[11.90]

"What is this curious brown stuff,"

said Ellen, "growing all over the rock?—like shriveled and dried-up leaves?

Isn't it curious? Part of it stands out like a leaf, and part of it sticks fast;

I wonder if it grows here, or what it is."

[11.91]

"Oh, never

mind," said the other; "it always grows on the rocks everywhere;

I don't know what it is, and what's more I don't care.

'Tain't worth

looking at. Come!"

[11.92]

Ellen

followed her. But presently the path entered

an open woodland, and now

her delight broke forth beyond bounds.

[the sublime?]

[11.93]

"Oh, how pleasant this is! How lovely

this is! Isn't it beautiful?" she exclaimed.

[11.94]

"Isn't

what beautiful? I do think you

are the queerest girl, Ellen."

[11.95]

"Why everything," said Ellen, not minding the latter part of

the sentence; " the ground is beautiful, and those tall trees, and that

beautiful blue sky—only look at it."

[11.96]

"The ground is all covered with stones and rocks—is

that what you call beautiful? and the trees are as homely as they can be,

with their great brown stems and no leaves. Come! what

are you staring at?"

[11.97]

Ellen's eyes were fixed on a string of

dark spots, which were rapidly passing overhead.

[11.98]

"Hark!" said she; "do you hear that noise? what is that? what

is that?"

[11.99]

"Isn't it

only a flock of ducks," said the

other, contemptuously; "come! do come!"

[11.100]

But Ellen was rooted to the ground, and her eyes followed the

airy travelers till the last one had quitted the piece of blue sky which the

surrounding woods left to be seen. And scarcely were these gone when a second

flight came in view, following exactly in the track of the first.

[11.101]

"Where are they going?" said Ellen.

[11.102]

"I am sure I don't know where

they are going; they never told me. I know where I

am going; I should like to know whether you are

going along with me."

[11.103]

Ellen, however, was in no hurry. The ducks had disappeared,

but her eye had caught something else that charmed it.

[11.104]

"What is this?" said Ellen.

[11.105]

"Nothing but moss."

[11.106]

"Is that moss! How beautiful! how green and soft it is! I

declare it's as soft as a carpet."

[11.107]

"As soft as

a carpet!" repeated the other: "I should like to see a carpet as soft as that!

you never did, I

guess."

[11.108]

"Indeed I have, though," said Ellen, who was gently jumping

up and down on the green moss to try its softness, with a face of great

satisfaction.

[11.109]

"I don't believe it a bit," said the other; "all the carpets

I ever saw were as hard as a board, and harder; as soft as that, indeed!"

[11.110]

"Well," said Ellen, still jumping up and down, with bonnet

off, and glowing cheek, and hair dancing about her face, "you may believe what

you like; but I've seen a carpet as soft as this, and softer too; only one,

though."

[11.111]

"What was it made of?"

[11.112]

"What other carpets are made of, I suppose. Come, I'll go

with you now. I do think this is the loveliest place I ever did see. Are there

any flowers here in the spring?"

[11.113]

"I don't know—yes, lots of 'em."

[11.114]

"Pretty ones?" said Ellen.

[11.115]

"You'd

think so, I suppose; I never look at 'em."

[11.116]

"Oh, how

lovely that will be!' said Ellen, clasping her hands;

"how pleasant it

must be to live in the country!"

[11.117]

"Pleasant, indeed!" said the other; "I

think it's hateful. You'd

think so, too, if you lived where I do. It makes me mad at granny every day

because she won't go to Thirlwall. Wait till we get out of the wood, and I'll

show you where I live. You can't see it from here."

[11.119]

Shocked a little at her companion's language, Ellen again

walked on in sober silence. Gradually the ground became more broken, sinking

rapidly from the side of the path, and rising again in a steep bank on the other

side of a narrow dell; both sides were thickly wooded, but stripped of green,

now, except where here and there a hemlock flung its graceful branches abroad

and stood in lonely beauty among its leafless companions. Now the gurgling of

waters was heard.

[11.120]

"Where is that?" said Ellen, stopping short.

[11.121]

"'Way down, down, at the bottom there. It's the brook."

[11.123]

"What brook? Not the same that goes by

Aunt Fortune's?"

[11.124]

"Yes, it's the very same. It's the

crookedest thing you ever saw.

It runs over there," said the speaker, pointing with her arm, "and then it takes

a turn and goes that way, and then it comes round so, and then it shoots off in

that way again and passes by your house; and after that the dear knows where it

goes, for I don't. But I don't suppose it could run straight if it was to try

to."

[11.125]

"Can't we get down to it?" said Ellen.

[11.126]

"To be sure we can, unless you're as afraid of steep banks as

you are of fences."

[11.127]

Very steep

indeed it was, and strewn with loose stones, but Ellen did not falter here, and

though once or twice in imminent danger of exchanging her cautious stepping for

one long roll to the bottom, she got there safely on her two feet.

When there, everything was forgotten in delight. It was a wild little

place. The high, close sides of the dell left only a little strip of sky

overhead; and at their feet ran the brook, much more noisy and lively here than

where Ellen had before made its acquaintance; leaping from rock to rock, eddying

round large stones, and boiling over the small ones, and now and then pouring

quietly over some great trunk of a tree that had fallen across its bed and

dammed up the whole stream. Ellen could scarcely contain herself at

the magnificence of many of the

waterfalls, the beauty of the little quiet pools where the water lay still

behind some large stone, and the variety of graceful tiny cascades.

[11.128]

"Look here,

[11.129]

"Black Falls," suggested the other.

[11.130]

"Black," said Ellen, dubiously, "why!—I

don't like that."

[11.131]

"Why the water's all dark and black,

don't you see?"

[11.132]

"Well," said Ellen; "let it be Black,

then; but I don't like it.

Now remember,—this is Niagara,—that is Black,—and this is

[11.133]

"If you are

a-going to name them all," said

[11.134]

"Oh, do let's!" said Ellen; "that will be lovely."

[11.135]

It proved a

rough way; but Ellen still thought and called it "lovely." Often by the side of

the stream there was no footing at all, and

the girls picked their way over the

stones, large and small, wet and dry, which strewed its bed; against which the

water foamed and fumed and fretted, as if in great impatience. It was

ticklish work getting along over these stones; now tottering on an unsteady one;

now slipping on a wet one; and every now and then making huge leaps from rock to

rock, which there was no other method of reaching, at the imminent hazard of

falling in. But they laughed at the danger; sprang on in great glee, delighted with the

exercise and the fun; didn't stay long enough anywhere to lose their balance,

and enjoyed themselves amazingly. There was many a hair-breadth escape; many

an almost sousing

[drenching]; but

that made it all the more lively. The brook formed, as

[11.136]

"I guess

we'd better get back into the lane now," said Miss Nancy, "we're a pretty good

long way from home."

End of Chapter 11 > Chapter 12 (partial)

![]()

![]()

—

[ ]