Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

from Chapter Eleven. The remainder of Anno 1620. [Mayflower Compact; Squanto; the Starving Time] |

|

Instructor’s notes re Chapter 11:

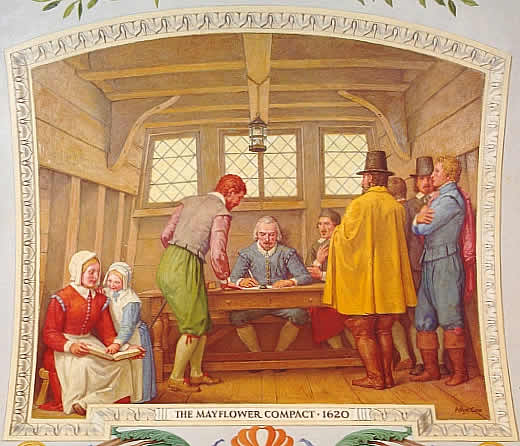

![]() The

Mayflower Compact is treasured

by American historians as a prototype or preview of the USA’s

Declaration

and

Constitution 150 years later. Both sets of documents establish a

written system

of laws and a

social contract governed by majority rule.

The

Mayflower Compact is treasured

by American historians as a prototype or preview of the USA’s

Declaration

and

Constitution 150 years later. Both sets of documents establish a

written system

of laws and a

social contract governed by majority rule.

![]() Typology

or parallels between Pilgrims and Jews of Exodus: When the ancient Jews

journeyed to the

Promised Land, they brought their own God, culture, and rules with them, ignoring the culture

of the established inhabitants (the Canaanites). Comparably, when the

Pilgrims come to America, they ignore the Indians’ way of life as “savage”

and irrelevant. By extension, the Pilgrims' narrative of immigration differs

from the standard immigrant narrative because the Pilgrims have no intention

of assimilating to the

pre-existing culture of the Indians.

Typology

or parallels between Pilgrims and Jews of Exodus: When the ancient Jews

journeyed to the

Promised Land, they brought their own God, culture, and rules with them, ignoring the culture

of the established inhabitants (the Canaanites). Comparably, when the

Pilgrims come to America, they ignore the Indians’ way of life as “savage”

and irrelevant. By extension, the Pilgrims' narrative of immigration differs

from the standard immigrant narrative because the Pilgrims have no intention

of assimilating to the

pre-existing culture of the Indians.

![]() “Covenant,” a concept inherited

from the relationship of Yahweh and the Jewish people, is the essential

concept by which the Pilgrims combine religious devotion and civil

government. (Covenant binds

people to each other on earth but also to God above, in contrast to modern

social contracts like the

Constitution which operate more exclusively

on the level of "We the people.")

“Covenant,” a concept inherited

from the relationship of Yahweh and the Jewish people, is the essential

concept by which the Pilgrims combine religious devotion and civil

government. (Covenant binds

people to each other on earth but also to God above, in contrast to modern

social contracts like the

Constitution which operate more exclusively

on the level of "We the people.")

![]() Euro-Immigrant guys gone wild!

As

the opening paragraph indicates, the Pilgrims land far north of their target

destination of Virginia. The fact that they're outside the supposed zone of

control inspires some of the non-Pilgrims on the ship to declare it's every man

for himself—a classic issue not only for all immigrants escaping from their

previous traditions but also colonial situations where the native culture has little authority,

as in other areas of European conquest like Africa, Asia, Africa, the Middle East.

Euro-Immigrant guys gone wild!

As

the opening paragraph indicates, the Pilgrims land far north of their target

destination of Virginia. The fact that they're outside the supposed zone of

control inspires some of the non-Pilgrims on the ship to declare it's every man

for himself—a classic issue not only for all immigrants escaping from their

previous traditions but also colonial situations where the native culture has little authority,

as in other areas of European conquest like Africa, Asia, Africa, the Middle East.

![]() Surprising Indian contact:

The Indian Samoset, who speaks some English, appears and

introduces Squanto, who had lived with his tribe on the land the Pilgrims

now occupy but was kidnapped and taken to Europe, only to escape and

return to Massachusetts. While Squanto was in Europe, all his

tribespeople were killed by the epidemics of the late 1610s, leaving the land

that the Pilgrims occupied empty.

Surprising Indian contact:

The Indian Samoset, who speaks some English, appears and

introduces Squanto, who had lived with his tribe on the land the Pilgrims

now occupy but was kidnapped and taken to Europe, only to escape and

return to Massachusetts. While Squanto was in Europe, all his

tribespeople were killed by the epidemics of the late 1610s, leaving the land

that the Pilgrims occupied empty.

![]()

from Chapter Eleven. The remainder of Anno 1620. [Mayflower Compact; Squanto; the Starving Time]

[¶11.1] I shall a little return back and begin with a combination [contract, covenant] made by them [the Pilgrims] before they came ashore, being the first foundation of their government in this place; occasioned partly by the discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers [passengers besides Pilgrims] amongst them had let fall from them in the ship—That when they came ashore they would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them, the patent they had being for Virginia, and not for New England, which belonged to another Government, with which the Virginia Company had nothing to do. And partly that such an act by them done (this their condition considered) might be as firm as any patent [official document], and in some respects more sure.

[Instructor's note: The non-Pilgrims' potential individualism and indifference to authority leads the Pilgrims to compose "The Mayflower Compact," a brief constitution, covenant, or social contract that anticipates American democracy and New England's commitment to a "commonwealth" for "the general Good of the Colony."]

|

[¶11.2] The form was as followeth. IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honor of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620. [50 signatures follow, including Bradford's] |

|

[¶11.3] After this they chose, or rather confirmed, Mr. John Carver (a man godly and well approved amongst them) their Governor for that year. And after they had provided a place for their goods, or common store, (which were long in unlading for want of boats, foulness of winter weather, and sickness of diverse,) and begun some small cottages for their habitation, as time would admitte, they met and consulted of laws and orders, both for their civil and military Government, as the necessity of their condition did require, still adding thereunto as urgent occasion in several times, and as cases did require. [contrast the Pilgrims’ inclination to meet with the individualistic, anti-government attitudes of other groups comprising the dominant culture.]

[The next paragraph (¶11.4) describes “the starving time” of the first winter, in which nearly half of the 102 Pilgrims perished. More positively, Bradford describes the ordeal as one in which individuals sacrifice for the community—an event he seems to remember later when he regrets the original community’s dispersal.]

[¶11.4] In these hard and difficult beginnings they found some discontents and murmurings arise amongst some, and mutinous speeches and carriages [behaviors] in other; but they were soon quelled and overcome by the wisdom, patience, and just and equal carriage [bearing] of things by the Governor and better part, which clave [cohered] faithfully together in the main. But that which was most sad and lamentable was, that in two or three months time, half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy [disease typical on long sea voyages resulting from lack of vitamin C] and other diseases, which this long voyage and their inaccomodate [inhospitable] condition had brought upon them; so as there died some times two or three [persons] a day, in the foresaid time; that of 100-odd persons, scarce 50 remained.

On Cole's

Hill overlooking

[¶11.5] And of these in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound persons, who, to their great commendations be it spoken, spared no pains, night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed [prepared] them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome [soiled] clothes, clothed and unclothed them; in a word, did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named; and all this willingly and cheerfully, without any grudging in the least, showing herein their true love unto their friends and brethren. A rare example and worthy to be remembered. Two of these seven were Mr. William Brewster, their reverend Elder, and Myles Standish, their Captain and military commander, unto whom myself, and many others, were much beholden in our low and sick condition. And yet the Lord so upheld these persons, as in this general calamity they were not at all infected either with sickness, or lameness. And what I have said of these, I may say of many others who died in this general visitation, and others yet living, that whilst they had health, yea, or any strength continuing, they were not wanting to any that had need of them. And I doubt not but their recompense is with the Lord.

[typology: Just as Bradford remembers the Jews of the Exodus story as “example(s) . . . worthy to be remembered,” the paragraph above describes the first settlers as a type for emulation or imitation, especially in contrast to the non-Separatists described in the next paragraph.]

[¶11.6] But I may not here pass by another remarkable passage not to be forgotten. As this calamity fell among the passengers that were to be left here to plant, and were hasted ashore and made to drink water, that the sea-men might have the more beer and one in his sickness desiring but a small can of beer, it was answered, that if he were their own father he should have none; the disease began to fall amongst them [the sea-men] also, so as almost half of their company died before they went away, and many of their officers and lustiest [most robust] men, as the boatswain, gunner, quarter-masters, the cook, and others. At which the master was something stricken and sent to the sick a shore and told the Governor he should send for beer for them that had need of it, though he drink water homeward bound.

[¶11.7] But now amongst his company [the shipmaster’s sailors] there was far another kind of carriage [behavior] in this misery than amongst the passengers [the Pilgrims]; for they that before had been boon companions in drinking and jollity in the time of their health and welfare, began now to desert one another in this calamity, saying they would not hazard [risk] their lives for them, they should be infected by coming to help them in their cabins, and so, after they came to die by it, would do little or nothing for them, but if they died let them die. But such of the passengers [Pilgrims] as were yet aboard showed them what mercy they could, which made some of their hearts relent, as the boatswain (and some others), who was a proud young man, and would often curse and scoff at the passengers; but when he grew weak, they had compassion on him and helped him; then he confessed he did not deserve it at their hands, he had abused them in word and deed. 0! saith he, you, I now see, show your love like Christians indeed one to another, but we let one another lie and die like dogs. Another lay cursing his wife, saying if it had not been for her he had never come this unlucky voyage, and anon [next] cursing his fellows, saying he had done this and that, for some of them, he had spent so much, and so much, amongst them, and they were now weary of him, and did not help him, having need. Another gave his companion all he had, if he died, to help him in his weakness; he went and got a little spice and made him a mess of meat once or twice, and because he died not so soon as he expected, he went amongst his fellows, and swore the rogue would cozen [trick] him, he would see him choked before he made him any more meat; and yet the poor fellow died before morning.

|

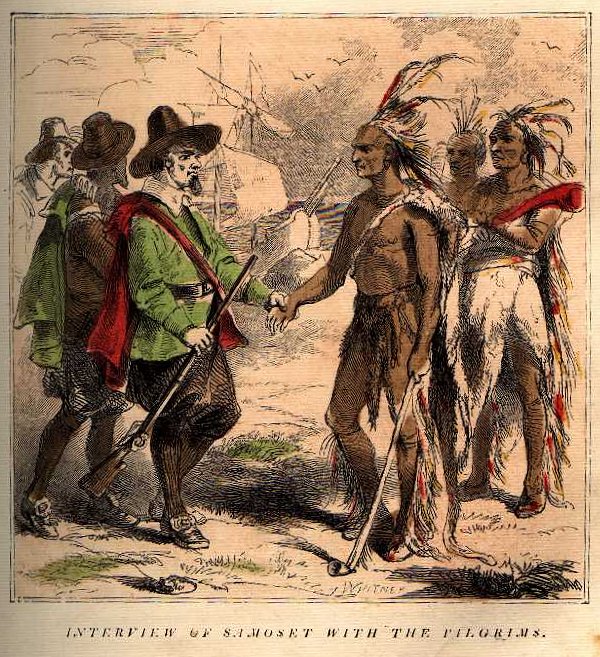

Samoset, an English-speaking Indian, appears . . . [¶11.8] All this while the Indians carne skulking [sneaking] about them, and would sometimes show themselves aloof [remote, unapproachable] off, but when any approached near them, they would run away. And once they stole away their [the Pilgrims’] tools where they had been at work, and were gone to dinner. But about the sixteenth of March a certain Indian came boldly amongst them, and spoke to them in broken English, which they could well understand, but marveled at it. At length they understood by discourse with him, that he was not of these parts, but belonged to the eastern parts, where some English-ships came to fish, with whom he was acquainted, and could name sundry of them by their names, amongst whom he had got his language. He became profitable to them in acquainting them with many things concerning the state of the country in the east-parts where he lived, which was afterwards profitable unto them; as also of the people here, of their names, number, and strength; of their situation and distance from this place, and who was chief amongst them. [¶11.9] His name was Samoset; he told them also of another Indian whose name was Squanto, a native of this place, who had been in England and could speak better English than himself. Being, after some time of entertainment and gifts, dismissed, a while after he carne again, and five more with him, and they brought again all the tools that were stolen away before, and made way for the coming of their great Sachem [chief, tribal leader], called Massasoit ; who, about four or five days after, carne with the chief of his friends and other attendance, with the aforesaid Squanto. |

|

|

Indian Relations: The Pilgrims negotiate with Samoset's chief Massasoit and make a written treaty prescribing the two groups relations with each other. (Massasoit and his people later join the Pilgrims for the "First Thanksgiving." (>in chapter 12) [¶11.10] With whom [Massasoit], after friendly entertainment, and some gifts given him, they made a peace with him (which hath now continued this 24 years) in these terms. 1. That neither he nor any of his, should injure or do hurt to any of their people. 2. That if any of his did any hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender, that they might punish him. 3. That if anything were taken away from any of theirs [the Pilgrims’], he [Massasoit] should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his. 4. If any did unjustly war against him [Massasoit], they [the Pilgrims] would aide him; if any did war against them, he [Massasoit] should aid them [the Pilgrims]. 5. He should send to his neighbors confederates, to certify them of this, that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace. [That is, different tribes should share members to prevent warfare or serve as hostages in case of war.] 6. That when their [the Indians’] men came to them [the Pilgrims], they [the Indians] should leave their bows and arrows behind them.

|

postcard of

statue of Massasoit, 1581-1661,

|

|

Squanto: An American Indian joins the Pilgrim Community, who now live on the land where his now-extinct tribe once lived [¶11.11] After these things he returned to his place called Sowams, some 40 miles from this place, but Squanto continued with them, and was their interpreter, and was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died. He was a native of this place, and scarce any left alive beside himself*. [*“scarce any left alive beside himself”: Another reference to the terrible epidemic affecting the Indians in the years before the Pilgrims' arrival. Squanto grew up among the Patuxet people who lived where the Pilgrims settled. [In 1605, before the epidemic, Squanto was kidnapped twice by European explorers. By the time he returned to his homeland in 1619, all his people were dead or dispersed. The Pilgrims settled the same area the following year, 1620. [Squanto’s desire to live in his homeland confirms a contrast between Western or modern peoples like the Pilgrims and local or traditional peoples like American Indians: Whereas the Pilgrims keep moving and changing in search of a promised land, Indians and other traditional peoples assume they already live in a promised land.] [¶11.12] He was carried away with diverse others by one Hunt, a master of a ship, who thought to sell them for slaves in Spain; but he got away for England, and was entertained by a merchant in London, and employed to Newfoundland and other parts, and lastly brought hither into these parts by one Mr. Dermer, a gentleman employed by Sir Ferdinando Gorges and others, for discovery, and other designs in these parts. . . .

|

recent popularizations of Squanto's story |

[¶11.13] But to return. The spring approaching, it pleased God the mortality [deadly disease] began to cease amongst them, and the sick and lame recovered apace, which put as it were new life into them [the community]; though they had borne their sad affliction with much patience and contentedness, as I think any people could do. But it was the Lord which upheld them, and had beforehand prepared them; many having long borne the yoke, yea from their youth. Many other smaller matters I omit, sundry of them having been already published in a journal [Mourt’s Relation] made by one of the company and some other passages of journeys and relations already published, to which I refer those that are willing to know them more particularly. And being now come to the 25th of March I shall begin the year 1621.

End Chapter 11