|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

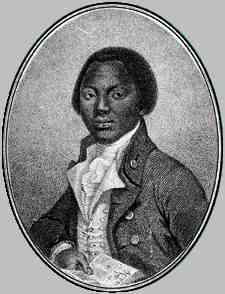

| classic slave narratives:

selections from The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, . . . the African by Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797) (London, 1789) |

|

Discussion questions

for American Immigrant Literature:

1. How does Equiano's

narrative differ from or resemble the immigrant narrative?

2. How does African America's

different origins (forced migration and slavery instead of voluntary migration

and opportunity) creat a

minority

narrative instead of an

immigrant

narrative?

3. What cultural consequences for African Americans

and the USA's dominant culture?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Maps relevant to Narrative of . . . Olaudah Equiano

|

|

Location of present-day Nigeria, which includes former territory of Benin Empire |

|

As para. 1.1 indicates, Equiano was born in Benen or Benin, a region of Africa that for 5 centuries (1440-1897) was organized as the Benin Empire, populated mostly by Edo peoples. (This Benin region and Empire do not overlap with modern Republic of Benin [formerly Dahomey], a nation to the immediate west of Nigeria.)

|

from Chapter 1 The author's account of his

country, and their manners and customs . . . |

[ch. 1, par. 1] . . . That part of Africa, known by the name of Guinea [west Africa region incl. Nigeria], to which the trade for slaves is carried on, extends along the coast above 3400 miles, from the Senegal to Angola, and includes a variety of kingdoms. Of these the most considerable is the kingdom of Benen [Benin] . . . This kingdom is divided into many provinces or districts: in one of the most remote and fertile of which, called Eboe [modern Ibo or Igbo, southern region of modern Nigeria; a.k.a. Biafra] , I was born, in the year 1745, in a charming fruitful vale [valley], named Effaka. . . . I had never heard of white men or Europeans, nor of the sea: and our subjection to the king of Benin was little more than nominal; for every transaction of the government, as far as my slender observation extended, was conducted by the chiefs or elders of the place. The manners and government of a people who have little commerce with other countries are generally very simple; and the history of what passes in one family or village may serve as a specimen of a nation.

[ch. 1, par. 2] My father was one of those elders or chiefs . . . . Those . . . chief men decided disputes and punished crimes; for which purpose they always assembled together. The proceedings were generally short; and in most cases the law of retaliation prevailed. I remember a man was brought before my father, and the other judges, for kidnapping a boy; and, although he was the son of a chief or senator, he was condemned to make recompense [restitution] by a man or woman slave. . . .

[ch. 1, par. 3] We are all of a nation of dancers, musicians and poets. Thus every great event, such as a triumphant return from battle, or other cause of public rejoicing is celebrated in public dances, which are accompanied with songs and music suited to the occasion. The assembly is separated into four divisions, which dance either apart or in succession, and each with a character peculiar to itself. The first division contains the married men, who in their dances frequently exhibit feats of arms, and the representation of a battle. To these succeed the married women, who dance in the second division. The young men occupy the third; and the maidens the fourth. [<highly structured traditional society] Each represents some interesting scene of real life, such as a great achievement, domestic employment, a pathetic story or some rural sport; and as the subject is generally founded on some recent event, it is therefore ever new. This gives our dances a spirit and variety which I have scarcely seen elsewhere. We have many musical instruments, particularly drums of different kinds . . . .

[ch. 1, par. 4] As our manners are simple, our luxuries are few [<contrast modern capitalism's multiplications of commodities and desires] . . . . Our manner of living is entirely plain . . . . Our vegetables are mostly plantains, eadas, yams, beans, and Indian corn. The head of the family usually eats alone; his wives and slaves have also their separate tables. Before we taste food we always wash our hands: indeed our cleanliness on all occasions is extreme; but on this it is an indispensable ceremony. After washing, libation is made, by pouring out a small portion of the food, in a certain place, for the spirits of departed relations, which the natives suppose to preside over their conduct and guard them from evil. They are totally unacquainted with strong or spirituous liquours; and their principal beverage is palm wine. . . . The same tree also produces nuts and oil. . . .

[ch. 1, par. 5] As we live in a country where nature is prodigal of her favours, our wants are few and easily supplied; of course we have few manufactures [industries]. . . . In such a state money is of little use; however we have some small pieces of coin, if I may call them such. They are made something like an anchor; but I do not remember either their value or denomination. We have also markets, at which I have been frequently with my mother. These are sometimes visited by stout mahogany-coloured men from the south west of us: we call them Oye-Eboe, which term signifies red men living at a distance. They generally bring us fire-arms, gunpowder, hats, beads, and dried fish. . . . They always carry slaves through our land; but the strictest account is exacted of their manner of procuring them before they are suffered to pass. Sometimes indeed we sold slaves to them, but they were only prisoners of war, or such among us as had been convicted of kidnapping or adultery, and some other crimes, which we esteemed heinous. . . .

![]()

|

from Chapter 2: The author's birth and parentage—His being kidnapped with his sister—Their separation-surprise at meeting again—. . . |

[ch. 2, par. 3] Generally when the grown people in the neighborhood were gone far in the fields to labour, the children assembled together in some of the neighbors' premises to play; and commonly some of us used to get up a tree to look out for any assailant, or kidnapper, that might come upon us; for they sometimes took those opportunities of our parents absence to attack and carry off as many as they could seize. One day, as I was watching at the top of a tree in our yard, I saw one of those people come into the yard of our next neighbor but one, to kidnap, there being many stout young people in it. Immediately on this I gave the alarm of the rogue, and he was surrounded by the stoutest of them, who entangled him with cords, so that he could not escape till some of the grown people came and secured him.

[ch. 2, par. 4] But alas! ere long it was my fate to be thus attacked, and to be carried off, when none of the grown people were nigh. One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls and in a moment seized us both, and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound, but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep, which allayed our misfortune for a short time. . . .

[ch. 2, par. 6] The next day proved a day of greater sorrow than I had yet experienced; for my sister and I were then separated, while we lay clasped in each other's arms. It was in vain that we besought them not to part us; she was torn from me, and immediately carried away, while I was left in a state of distraction not to be described. I cried and grieved continually; and for several days I did not eat anything but what they forced into my mouth. At length, after many days travelling, during which I had often changed masters I got into the hands of a chieftain, in a very pleasant country. This man had two wives and some children, and they all used me extremely well, and did all they could to comfort me; particularly the first wife, who was something like my mother. Although I was a great many days journey from my father's house, yet these people spoke exactly the same language with us. . . .

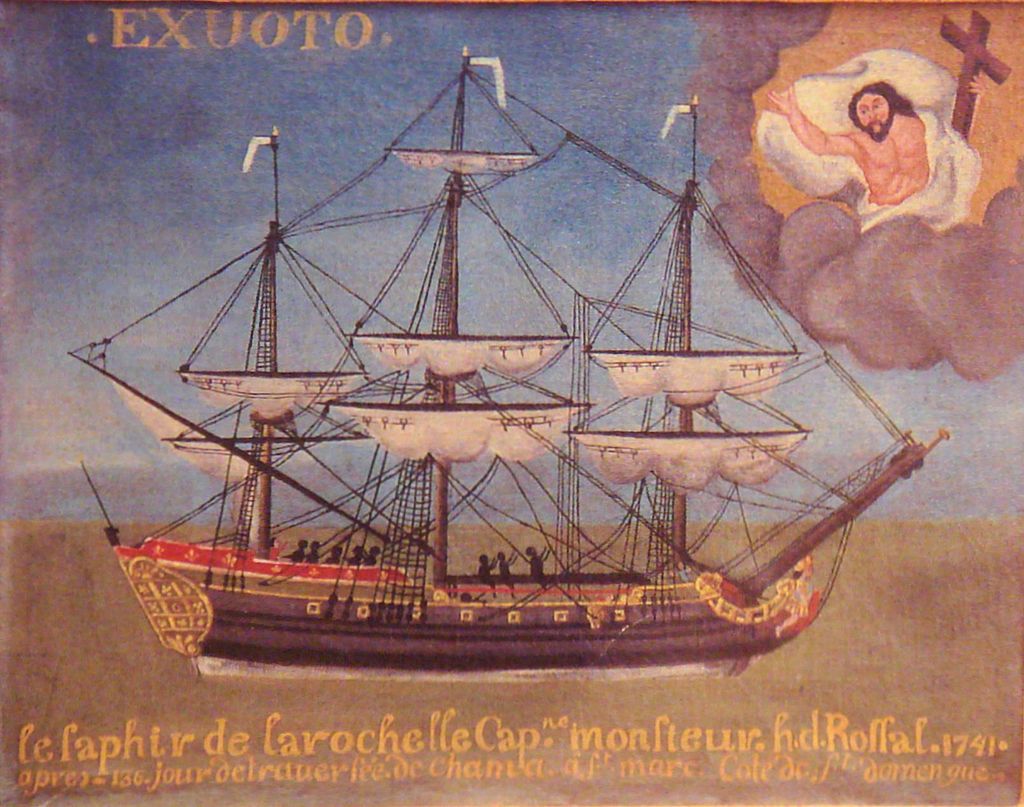

|

ch. 2, par. 16] The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled and tossed up to see if I were sound by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke (which was very different from any I had ever heard), united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country. [note reversal of Western racial color code; white complexions = bad spirits] [ch. 2, par. 17] When I looked round the ship too and saw a large furnace or copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, everyone of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair. They told me I was not; . . . Soon after this the blacks who brought me on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair. |

|

[ch. 2, par. 18] I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore which I now considered as friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in preference to my present situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind, still heightened by my ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down hinder [under] the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench and crying together,

ch. 2,

par. 18] I became so

sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste

anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to

my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and on my refusing to eat,

one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across I think the windlass

and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced

anything of this kind before; and although, not being used to the water

[the ocean], I

naturally feared that element the first time I saw it, yet nevertheless, could I

have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not;

and, besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down

to the decks, lest we should leap into the water .

. . .

[ch. 2, par. 20] . . . At

last, when the ship we were in had got in all her cargo, they made ready with

many fearful noises, and we were all put under deck, so that we could not see

how they managed the vessel. But this disappointment was the least of my sorrow.

The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome,

that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been

permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship's

cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness

of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship,

which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost

suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became

unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and

brought on a

sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the

improvident avarice

[reckless greed], as I may call it, of their purchasers.

[ch. 2, par. 21] This wretched situation was again

aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth

of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost

suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the

whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was

soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always

on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I

expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost

daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon

put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep

much more happy than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as

often wished I could change my condition for theirs.

[ch. 2, par. 21] Every circumstance I met with served only to render my

state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty

of the whites. One day they had taken a number of fishes and when they had

killed and satisfied themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our

astonishment who were on the deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat as

we expected, they tossed the remaining fish into the sea again, although we

begged and prayed for some as well as we could, but in vain; and some of my

countrymen, being pressed by hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no

one saw them, of trying to get a little privately; but they were discovered, and

the attempt procured them some very severe floggings. One day, when we had a

smooth sea and moderate wind, two of my wearied countrymen who were chained

together (I was near them at the time), preferring death to such a life of

misery, somehow made through the nettings and

jumped into the sea: immediately

another quite dejected fellow, who, on account of his illness, was suffered to

be out of irons, also followed their example; and I believe many more would very

soon have done the same if they had not been prevented by the ship's crew, who

were instantly alarmed. Those of us that were the most active were in a moment

put down under the deck, and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the

people of the ship as I never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat out to

go after the slaves. However two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the

other, and afterwards flogged him unmercifully for thus attempting to prefer

death to slavery. . . .

|

[ch. 2, par. 22] At last we came in sight of the island of Barbadoes, at which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us. We did not know what to think of this; but as the vessel drew nearer we plainly saw the harbor, and other ships of different kinds and sizes; and we soon anchored amongst them off Bridge Town. Many merchants and planters now came on board, though it was in the evening. They put us in separate parcels, and examined us attentively. They also made us jump, and pointed to the land, signifying we were to go there. We thought by this we should be eaten by those ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions, insomuch that at last the white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us. They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land, where we should see many of our country people. This report eased us much; and sure enough, soon after we were landed, there came to us Africans of all languages. We were conducted immediately to the merchant's yard, where we were all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age. . . . |

|

![]()

|

from Chapter 3 The author is carried to Virginia—His distress—Surprise at seeing a picture and a watch—. . . |

[ch. 3, par. 1] I now totally lost the small remains of comfort I had

enjoyed in conversing with my countrymen; the women too, who used to wash and

take care of me, were all gone different ways, and I never saw one of them

afterwards.

[ch. 3, par. 2] I stayed in this island

[Barbadoes] for a few days; I believe it

could not be above a fortnight [two weeks]; when I and some few more slaves, that were not

saleable amongst the rest, from very much fretting, were shipped off in a sloop

for North America. On the passage we were better treated than when we were

coming from Africa, and we had plenty of rice and fat pork. We were landed up a

river a good way from the sea, about Virginia county, where we saw few or none

of our native Africans, and not one soul who could talk to me. I was a few weeks

weeding grass, and gathering stones in a plantation; and at last all my

companions were distributed different ways, and only myself was left.

I was now

exceedingly miserable, and thought myself worse off than any of the rest of my

companions; for they could talk to each other, but I had no person to speak to

that I could understand. In this state I was constantly grieving and pining, and

wishing for death rather than anything else.

[ch. 3, par. 3] While I was in this plantation the gentleman, to whom I

suppose the estate belonged, being unwell, I was one day sent for to his

dwelling house to fan him; when I came into the room where he was I was very

much affrighted at some things I saw, and the more so as I had seen

a black

woman slave as I came through the house, who was cooking the dinner, and the

poor creature was cruelly loaded with various kinds of iron machines; she had

one particularly on her head, which locked her mouth so fast that she could

scarcely speak; and could not eat nor drink. I was much astonished and shocked

at this contrivance, which I afterward learned was called the iron muzzle. Soon

after I had a fan put into my hand, to fan the gentleman while he slept; and so

I did indeed with great fear.

[ch. 3, par. 4] While he was fast asleep I indulged

myself a great deal in looking about the room, which to me appeared very fine

and curious. The first object that engaged my attention was a watch which hung

on the chimney, and was going. I was quite surprised at the noise it made and

was afraid it would tell the gentleman anything I might do amiss

[wrong]: and when I

immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared

constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never

seen such things as these before. At one time I thought it was something

relative to magic . . . .

[ch. 3, par. 5] I had been some time in this miserable, forlorn, and much

dejected state, without having anyone to talk to, which made my life a burden,

when the kind and unknown hand of the Creator (who in very deed leads the blind

in a way they know not) now began to appear, to my comfort; for one day the

captain of a merchant ship, called the Industrious Bee, came on some business to

my master's house. This gentleman, whose name was Michael Henry Pascal, was a

lieutenant in the royal navy, but now commanded this trading ship, which was

somewhere in the confines of the county many miles off.

[ch. 3, par. 6] While he was at my master's house

it happened that he saw me, and liked me so well that he made a purchase of me.

I think I have often heard him say he gave thirty or forty pounds sterling for

me; but I do not now remember which. However, he meant me for a present to some

of his friends in England: and I was sent accordingly from the house of my then

master, one Mr. Campbell, to the place where the ship lay; I was conducted on

horseback by an elderly black man (a mode of travelling which appeared very odd

to me). When I arrived I was carried on board a fine large ship, loaded with

tobacco, etc. and just ready to sail for England. I now thought my condition

much mended; I had sails to lie on, and plenty of good vitals

[foodstuffs] to eat; and

everybody on board used me very kindly, quite contrary to what I had seen of any

white people before; I therefore began to think that they were not all of the

same disposition. A few days after I was on board we sailed for England.

[ch. 3, par. 7] I was still at a loss to conjecture my destiny. By this

time, however, I could smatter a little imperfect English; and I wanted to know

as well as I could where we were going. Some of the people of the ship used to

tell me they were going to carry me back to my own country, and this made me

very happy. I was quite rejoiced at the sound of going back; and thought if I

should get home what wonders I should have to tell. But I was reserved for

another fate, and was soon undeceived when we came within sight of the

English coast. While I was on board this ship, my captain and master named me

Gustavus Vassa. I at that time began to understand him a little, and refused to

be called so, and told him as well as I could that I would be called Jacob; but

he said I should not, and still called me Gustavus; and when I refused to answer

to my new name, which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff

[fisticuff]; so at length I

submitted, and was obliged to bear the present name, by which I have been known

ever since. . . .

[ch. 3, par.8] There was on board the ship a young lad who had never been at sea before, about four or five years older than myself: his name was Richard Baker. He was a native of America, had received an excellent education, and was of a most amiable temper. Soon after I went on board he showed me a great deal of partiality and attention, and in return I grew extremely fond of him. We at length became inseparable; and, for the space of two years, he was of very great use to me, and was my constant companion and instructor. . . .

[ch. 3, par. 12] I had often seen my master and Dick employed in reading; and I had a great curiosity to talk to the books, as I thought they did; and so to learn how all things had a beginning: for that purpose I have often taken up a book, and have talked to it, and then put my ears to it, when alone, in hopes it would answer me; and I have been very much concerned when I found it remained silent. . . .

[ch. 3, par. 14]

. . . When we arrived at Guernsey, my master placed me to board and lodge with

one of his mates, who had a wife and family there; and some months afterwards he

went to England, and left me in care of this mate, together with my friend Dick:

This mate had a little daughter, aged about five or six years, with whom I used

to be much delighted.

[ch. 3, par. 15] I had often observed that when her mother washed her

face it looked very rosy; but when she washed mine it did not look so: I

therefore tried often times myself if I could not by washing make my face of the

same colour as my little playmate (Mary), but it was all in vain; and I now

began to be mortified at the difference in our complexions. This woman behaved

to me with great kindness and attention; and taught me everything in the same

manner as she did her own child, and indeed in every respect treated me as such.

I remained here till the summer of the year 1757; when my master, being

appointed first lieutenant of his majesty's ship the Roebuck, sent for Dick and

me, and his old mate: on this we all left Guernsey, and set out for England in a

sloop bound for London. . . .

![]()

|

from CHAP. IV |

[4.1] . . . I have often reflected with surprise that I never felt half the alarm at any of the numerous dangers I have been in, that I was filled with at the first sight of the Europeans . . . . That fear, however, which was the effect of my ignorance, wore away as I began to know them. I could now speak English tolerably well, and I perfectly understood every thing that was said. I now not only felt myself quite easy with these new countrymen, but relished their society and manners. I no longer looked upon them as spirits, but as men superior to us; and therefore I had the stronger desire to resemble them; to imbibe their spirit, and imitate their manners; I therefore embraced every occasion of improvement; and every new thing that I observed I treasured up in my memory. I had long wished to be able to read and write; and for this purpose I took every opportunity to gain instruction, but had made as yet very little progress. However, when I went to London with my master, I had soon an opportunity of improving myself, which I gladly embraced. Shortly after my arrival, he sent me to wait upon the Miss Guerins, who had treated me with much kindness when I was there before; and they sent me to school.

[4.2] While I was attending these ladies their servants told me I could not go to Heaven unless I was baptized. This made me very uneasy; for I had now some faint idea of a future state: accordingly I communicated my anxiety to the eldest Miss Guerin, with whom I was become a favourite, and pressed her to have me baptized; when to my great joy she told me I should. She had formerly asked my master to let me be baptized, but he had refused; however she now insisted on it; and he being under some obligation to her brother complied with her request; so I was baptized in St. Margaret's church, Westminster, in February 1759, by my present name. The clergyman, at the same time, gave me a book, called a Guide to the Indians, written by the Bishop of Sodor and Man. On this occasion Miss Guerin did me the honour to stand as godmother . . .

[4.3] The Namur* being again got ready for sea, my master, with his gang, was ordered on board; and, to my no small grief, I was obliged to leave my school-master, whom I liked very much, and always attended while I stayed in London, to repair on board with my master. Nor did I leave my kind patronesses, the Miss Guerins, without uneasiness and regret. They often used to teach me to read, and took great pains to instruct me in the principles of religion and the knowledge of God. I therefore parted from those amiable ladies with reluctance; after receiving from them many friendly cautions how to conduct myself, and some valuable presents. [Namur = name of ship, possibly named for Belgian city of Namur; probably unrelated to Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner of Marvel Comics]

[4.3a] I had frequently told several people, in my excursions on shore, the story of my being kidnapped with my sister . . .

[4.5] [1762; Olaudah is about 17] . . . I thought now of nothing but being freed, and working for myself, and thereby getting money to enable me to get a good education; for I always had a great desire to be able at least to read and write; and while I was on shipboard I had endeavoured to improve myself in both. While I was in the Ætna particularly, the captain's clerk taught me to write, and gave me a smattering of arithmetic as far as the rule of three. . . .

[4.6a] When I came there [the Thames River in London] Captain Doran asked me if I knew him; I answered that I did not; 'Then,' said he 'you are now my slave.' I told him my master could not sell me to him, nor to any one else. 'Why,' said he, 'did not your master buy you?' I confessed he did. 'But I have served him,' said I, 'many years, and he has taken all my wages and prize-money, for I only got one sixpence during the war; besides this I have been baptized; and by the laws of the land no man has a right to sell me:' And I added, that I had heard a lawyer and others at different times tell my master so. They both then said that those people who told me so were not my friends; but I replied—it was very extraordinary that other people did not know the law as well as they.

[4.6b] Upon this Captain Doran said I talked too much English; and if I did not behave myself well, and be quiet, he had a method on board to make me. . . .

|

from CHAP. V. [1763-66, mostly in Caribbean] |

|

[5.4] At the sight of this land of bondage, a fresh horror ran through all my frame, and chilled me to the heart. My former slavery now rose in dreadful review to my mind, and displayed nothing but misery, stripes [whipping], and chains . . . I now knew what it was to work hard; I was made to help to unload and load the ship. And, to comfort me in my distress in that time, two of the sailors robbed me of all my money, and ran away from the ship. I had been so long used to an European climate that at first I felt the scorching West India sun very painful . . . . [5.9] While I was thus employed by my master I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them. When we have had some of these slaves on board my master's vessels to carry them to other islands, or to America, I have known our mates to commit these acts most shamefully, to the disgrace, not of Christians only, but of men. I have even known them gratify their brutal passion with females not ten years old; and these abominations some of them practised to such scandalous excess, that one of our captains discharged the mate and others on that account. And yet in Montserrat I have seen a negro man staked to the ground, and cut most shockingly, and then his ears cut off bit by bit, because he had been connected with a white woman who was a common prostitute: as if it were no crime in the whites to rob an innocent African girl of her virtue; but most heinous in a black man only to gratify a passion of nature, where the temptation was offered by one of a different colour, though the most abandoned woman of her species. . . . |

|

|

from CHAP. VI (Equiano's slavery in the Caribbean Islands continues, but he begins to go into part-time business for himself) |

|

[6.3] After I had been sailing for some time with this captain, at length I endeavoured to try my luck and commence merchant. I had but a very small capital to begin with; for one single half bit, which is equal to three pence in England, made up my whole stock. However I trusted to the Lord to be with me; and at one of our trips to St. Eustatia, a Dutch island, I bought a glass tumbler with my half bit, and when I came to Montserrat I sold it for a bit, or sixpence. Luckily we made several successive trips to St. Eustatia (which was a general mart for the West Indies, about twenty leagues from Montserrat); and in our next, finding my tumbler so profitable, with this one bit I bought two tumblers more; and when I came back I sold them for two bits, equal to a shilling sterling. When we went again I bought with these two bits four more of these glasses, which I sold for four bits on our return to Montserrat; and in our next voyage to St. Eustatia I bought two glasses with one bit, and with the other three I bought a jug of Geneva, nearly about three pints in measure. When we came to Montserrat I sold the gin for eight bits, and the tumblers for two, so that my capital now amounted in all to a dollar, well husbanded and acquired in the space of a month or six weeks, when I blessed the Lord that I was so rich. As we sailed to different islands, I laid this money out in various things occasionally, and it used to turn out to very good account, especially when we went to Guadaloupe, Grenada, and the rest of the French islands. Thus was I going all about the islands upwards of four years, and ever trading as I went, during which I experienced many instances of ill usage, and have seen many injuries done to other negroes in our dealings with Europeans: and, amidst our recreations, when we have been dancing and merry-making, they, without cause, have molested and insulted us. . . . |

|

[6.8] I determined to make every exertion to obtain my freedom, and to return to Old England. For this purpose I thought a knowledge of navigation might be of use to me; for, though I did not intend to run away unless I should be ill used, yet, in such a case, if I understood navigation, I might attempt my escape in our sloop . . . .

[6.10] We soon got loaded again, and returned to Montserrat; and there, amongst the rest of the islands, I sold my goods well; and in this manner I continued trading during the year 1764; meeting with various scenes of imposition, as usual. . . .

![]()

|

from CHAP. VII. (Equiano buys his freedom) |

[7.1] Every day now brought me nearer my freedom, and I was impatient till we proceeded again to sea, that I might have an opportunity of getting a sum large enough to purchase it. I was not long ungratified; for, in the beginning of the year 1766, my master bought another sloop, named the Nancy, the largest I had ever seen. She was partly laden, and was to proceed to Philadelphia . . . .

[7.2] We arrived safe and in good time at Philadelphia, and I sold my goods there chiefly to the Quakers. They always appeared to be a very honest discreet sort of people, and never attempted to impose on me; I therefore liked them, and ever after chose to deal with them in preference to any others. [Though Equiano’s master is a Quaker and a slave-trader, the Quakers were the most abolitionist religious denomination in colonial and postcolonial America.] One Sunday morning while I was here, as I was going to church, I chanced to pass a meeting-house. The doors being open, and the house full of people, it excited my curiosity to go in. When I entered the house, to my great surprise, I saw a very tall woman standing in the midst of them, speaking in an audible voice something which I could not understand. [In addition to abolitionist movements, 18th-century Quakers may have been the first Christian denomination permitting women to speak in church services.]

[7.2a] Having never seen anything of this kind before, I stood and stared about me for some time, wondering at this odd scene. As soon as it was over I took an opportunity to make inquiry about the place and people, when I was informed they were called Quakers. I particularly asked what that woman I saw in the midst of them had said, but none of them were pleased to satisfy me; so I quitted them, and soon after, as I was returning, I came to a church crowded with people; the church-yard was full likewise, and a number of people were even mounted on ladders, looking in at the windows. I thought this a strange sight, as I had never seen churches, either in England or the West Indies, crowded in this manner before.

[7.2b] I therefore made bold to ask some people the meaning of all this, and they told me the Rev. Mr. George Whitfield was preaching. I had often heard of this gentleman, and had wished to see and hear him; but I had never before had an opportunity. I now therefore resolved to gratify myself with the sight, and I pressed in amidst the multitude. When I got into the church I saw this pious man exhorting the people with the greatest fervour and earnestness, and sweating as much as I ever did while in slavery on Montserrat beach. I was very much struck and impressed with this; I thought it strange I had never seen divines exert themselves in this manner before, and I was no longer at a loss to account for the thin congregations they preached to. [<Whitfield (1714-1770) pioneered the emotional style of preaching associated with “The Great Awakening” of the late 1700s and the “Second Great Awakening” of the early 1800s] . . .

[7.3] My traffic [business, commerce] had hitherto succeeded so well with me, that I thought, by selling my goods when we arrived at Montserrat, I should have enough to purchase my freedom. But, as soon as our vessel arrived there, my master came on board, and gave orders for us to go to St. Eustatia, and discharge our cargo there, and from thence proceed for Georgia. . . . After we had discharged our cargo there we took in a live cargo, as we call a cargo of slaves. Here I sold my goods tolerably well . . . . I longed to get back to Montserrat and procure my freedom, which I expected to be able to purchase when I returned. . . .

[7.4] We set sail once more for Montserrat, and arrived there safe; but much out of humour with our friend the silversmith. When we had unladen the vessel, and I had sold my venture, finding myself master of about forty-seven pounds, I consulted my true friend, the Captain, how I should proceed in offering my master the money for my freedom. He told me to come on a certain morning, when he and my master would be at breakfast together. Accordingly, on that morning I went, and met the Captain there, as he had appointed. When I went in I made my obeisance to my master, and with my money in my hand, and many fears in my heart, I prayed him to be as good as his offer to me, when he was pleased to promise me my freedom as soon as I could purchase it. . . .

[7.4a] My master then said, he would not be worse than his promise; and, taking the money, told me to go to the Secretary at the Register Office, and get my manumission drawn up. These words of my master were like a voice from heaven to me . . . . As soon as the first transports of my joy were over, and that I had expressed my thanks to these my worthy friends in the best manner I was able, I rose with a heart full of affection and reverence, and left the room, in order to obey my master's joyful mandate of going to the Register Office. As I was leaving the house I called to mind the words of the Psalmist, in the 126th Psalm, and like him, 'I glorified God in my heart, in whom I trusted.' These words had been impressed on my mind from the very day I was forced from Deptford to the present hour, and I now saw them, as I thought, fulfilled and verified. My imagination was all rapture as I flew to the Register Office, and, in this respect, like the apostle Peter, (whose deliverance from prison was so sudden and extraordinary, that he thought he was in a vision) I could scarcely believe I was awake. Heavens! who could do justice to my feelings at this moment! Not conquering heroes themselves, in the midst of a triumph—Not the tender mother who has just regained her long-lost infant, and presses it to her heart—Not the weary hungry mariner, at the sight of the desired friendly port—Not the lover, when he once more embraces his beloved mistress, after she had been ravished from his arms!—All within my breast was tumult, wildness, and delirium! My feet scarcely touched the ground, for they were winged with joy, and, like Elijah, as he rose to Heaven, they 'were with lightning sped as I went on.' Every one I met I told of my happiness, and blazed [told excitedly] about the virtue of my amiable master and captain.

[7.5] When I got to the office and acquainted the Register with my errand he congratulated me on the occasion, and told me he would draw up my manumission for half price, which was a guinea. I thanked him for his kindness; and, having received it and paid him, I hastened to my master to get him to sign it, that I might be fully released. Accordingly he signed the manumission that day, so that, before night, I who had been a slave in the morning, trembling at the will of another, was become my own master, and completely free. I thought this was the happiest day I had ever experienced; and my joy was still heightened by the blessings and prayers of the sable [black] race, particularly the aged, to whom my heart had ever been attached with reverence.

[7.6] As the form of my manumission has something peculiar in it, and expresses the absolute power and dominion one man claims over his fellow, I shall beg leave to present it before my readers at full length:

[7.7] Montserrat.—To all men unto whom these presents shall come: I Robert King, of the parish of St. Anthony in the said island, merchant, send greeting: Know ye, that I the aforesaid Robert King, for and in consideration of the sum of seventy pounds current money of the said island, to me in hand paid, and to the intent that a negro man-slave, named Gustavus Vassa, shall and may become free, have manumitted, emancipated, enfranchised, and set free, and by these presents do manumit, emancipate, enfranchise, and set free, the aforesaid negro man-slave, named Gustavus Vassa, for ever, hereby giving, granting, and releasing unto him, the said Gustavus Vassa, all right, title, dominion, sovereignty, and property, which, as lord and master over the aforesaid Gustavus Vassa, I had, or now I have, or by any means whatsoever I may or can hereafter possibly have over him the aforesaid negro, for ever. In witness whereof I the abovesaid Robert King have unto these presents set my hand and seal, this tenth day of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and sixty-six.

Robert King.

Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of Terrylegay, Montserrat.

Registered the within manumission at full length, this eleventh day of July, 1766, in liber D.

Terrylegay, Register.

[Instructor's note: Equiano is app. 21 years old when he buys himself from his master. He would soon return to England. He continued to work as a sailor, married, and lived another 31 years until 1797. His narrative is considerably longer than these excerpts and includes many adventures including an expedition to the Arctic.]

[7.8] In short, the fair as well as black people immediately styled me by a new appellation, to me the most desirable in the world, which was Freeman, and at the dances I gave my Georgia superfine blue clothes made no indifferent appearance, as I thought. Some of the sable females, who formerly stood aloof, now began to relax and appear less coy; but my heart was still fixed on London, where I hoped to be ere long. So that my worthy captain and his owner, my late master, finding that the bent of my mind was towards London, said to me, 'We hope you won't leave us, but that you will still be with the vessels.' Here gratitude bowed me down; and none but the generous mind can judge of my feelings, struggling between inclination and duty. [compare Charlotte Temple] . . . .

![]()

THE END.