|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

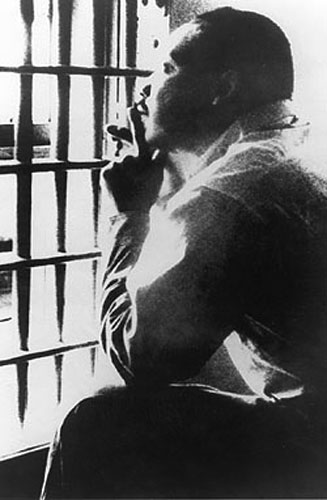

Passages on Non-Violent Resistance from Martin Luther King's Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963) |

|

Dr. Martin Luther King,

Letter from Birmingham City Jail.

1963.

A

Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ed. James Melvin Washington.

San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1986.

289-302.

My dear Fellow Clergymen,

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I

came across your recent statement calling our present activities “unwise and

untimely.”

Seldom, if ever, do I pause to answer criticism of my work

and ideas. . . .

But since I feel that you are men of genuine good

will and your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I would like to answer your

statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms. . . .

In any

nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: (1) collection of the facts

to determine whether injustices are alive, (2) negotiation, (3)

self-purification, and (4) direct

action.

We have gone through all of these steps on Birmingham. . .

.

You may well ask, “Why direct action?

Why sit-ins, marches, etc.?

Isn’t negotiation a better path?”

You are exactly right in your call for negotiation.

Indeed, this is the purpose of direct action.

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a

crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has constantly

refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.

It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no

longer be ignored. . . .

Just as

Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that

individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the

unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, we must see the

need of having nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that

will help men to rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the

majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. . . .

You express a great deal of anxiety over our

willingness to break laws.

This is certainly a legitimate concern.

Since we so diligently urge people to obey the

Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, it

is rather strange and paradoxical to find us consciously breaking laws.

One may well ask, “How can you advocate breaking

some laws and obeying others?”

The answer is found in the fact that there are

two types of

laws: there are just and there are

unjust laws.

I would agree with

Saint Augustine that “ An unjust law is

no law at all.”

Now what is the difference between the two?

How does one determine when a law is just or unjust?

A just law is a man-made code that squares with the

moral law or the law of God.

An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with

the moral law.

To put it in the terms of

Saint Thomas Aquinas, an unjust law is a

human law that is not rooted in eternal and natural law.

Any law that uplifts human personality is just.

Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.

All segregation statutes are unjust because

segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality.

It gives the segregator a false sense of

superiority, and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. . . .

[M]aybe the South, the nation, and the world are in

dire need of creative extremists.

—

[ ]