|

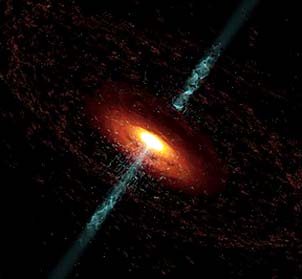

quasar |

LITR 3731 Creative Writing 2009 Final Exam Submissions Essay 1 on fiction |

|

Peter Becnel

Ten Pages For Your Pleasure

When I signed up for Creative Writing this semester, I had never written any fiction or poetry, and I was excited to take a class which assigned creative writing work. I am still excited about creative writing, the frustrating, exhausting, rewarding process that it is, and by taking this class, I have gained a new awareness of the values of writing, reading and teaching. I plan to apply my creative writing experience in this class to the public school class I hope to teach. Creative writing skills are far more important than term paper skills. Perhaps not for a students ability to do well in his classes, or on standardized tests, but certainly for his ability to communicate through writing. This skill will keep students writing, even after required coursework and standardized testing are finished .

The most important lesson that I learned from Creative Writing class this semester, is the importance of writing fiction to the development of capable writers; specifically the importance of integrating Creative Writing into the public school curriculum. The tendency in the public school system is to focus on term paper writing, structured and formulaic, because these are the writing skills students will be evaluated for come standardized test time. Through my years of experience in the subject, I have become an increasingly competent term paper writer; my participation this semester demonstrated the areas in which my writing skills are most lacking. I am not always capable of communicating what I mean. More than anything, creative writing is about forming a comprehensible idea and being able to communicate that idea effectively by any means necessary. In one respect this is the goal of structured term-paper style writing in public schools. However, this type of written medium breeds writers who are only capable of following a template, not writers who are able to communicate their thoughts and feelings in print regardless of standardized restrictions. Students with good creative writing skills are students who are empowered to write what they want, not what they think their instructor wants them to write.

During a field work experience for an Education class, I observed an Eighth Grade classroom, in which the students were presenting narratives that they had written throughout the semester. The effects of term paper dominant writing instruction were apparent in all of their work. Many of the stories were written under the same basic formulaic structure, most of the narratives were written memories, like structured journal entries, and few of the students seemed interested in pursuing a fictional story. The greatest problem that I saw with these narratives, was an issue that I presented in class during my own writing workshop; many of the stories lacked a climax. The lack of climax in the students' work is symptomatic of a lack of understanding about narrative writing. Climax in an essential ingredient to a satisfactory narrative.

The greatest stumbling block I faced while writing fiction this semester, was the breaking of all of the bonds I have formed over my years of experience with standardized writing. The effect of term-paper writing are demonstrated most apparently in my dialog. (An issue that both Dr. White, and the creative writing workshop brought to my attention) I must be extremely careful to use contractions when writing dialog, because my mind automatically edits them out of everything I write. Another example: the formation of a working narrative requires the writer to demonstrate the story as it unfolds, through the actions and speech of the characters. When writing a term paper, it is essential that you tell the reader what you are going to write about before you write about it. This appeals to the need of a writer to make the reader “willing to wait [for something] until the narrator finds out” and is an essential part of keeping the reader hooked.

Through workshop, I learned about the necessary balance that must exist between dialog and narrative. My own story was originally too dependent on dialog, the lack of narrative failed in creating a world in which my characters lived. Without the necessary narration, characters operate very much like chess pieces without a board, and the reading experience becomes very uninteresting. The writer does not succeed in creating a world, simply speech in a vacuum. This point was emphasized by Dr. White throughout the course, however, I did not realize how to apply the balance of narrative and dialog until I wrote my own piece, and spent time in workshop analyzing other writer's work. The most successful, well composed pieces throughout our course were primarily reliant on narrative, but also included a good deal of dialog; somewhere around a sixty/forty split. I do not say this to undermine the importance of dialog in fiction, certainly, if a writer relies too heavily on narrative “[he] will have to explain more as author and show less. This makes it more difficult for readers to enter the story.” It also makes it more difficult for the reader to trust the story. An example of this occurred in the final fiction workshop, when a piece was read that was told almost exclusively in a first person narrative form. Without the necessary dialog to give the reader a first-hand account of the actions being described it was easy as the reader to wonder if we were receiving an honest retelling of the story.

Assembling a work of fiction is an incredibly challenging task because there are so many factors to consider, and as Karen Heidrich puts it, “knowing what the pieces are does not make the process easier.” Making an entire world come to life, regardless of how well controlled or small that world is, is quite a challenge. The process can be overwhelming. When I was approaching my original draft, I approached the story as if it were the first chapter of a longer work. Most of the story became a long expository fictional tour of a grocery store. I placed myself within impossible parameters. Even in this mundane situation I attempted to provide the reader with friction.

One of the points from the text that left its greatest impression on me is “tension in fiction is what gives it energy and vitality. It's what keeps the reader reading.” A job interview and a tour of a grocery store are hardly the breeding ground for friction; I attempted to remedy this problem by creating characters with personalities that were naturally contradictory. To a certain extent this worked, however the story was a waste of paper. It was far to reliant on dialog. I managed to create a series of interesting chess pieces that had no board in which to play on. All elements of tension “consist of pitting one element against another.” I carefully considered the notion of tension in my rewrite.

Another issue that I encountered in creating my fiction submission was my tendency to want to include everything. This issue can best be described as the distinction between “clock time” and “psychological time”. Our texts explanation of the difference between these two notions of time was certainly eye-opening to me. It is not the goal of the writer to communicate a piece in real-time of “clock time” rather it is the goal of the writer to include the most important scenes so that the story is reconstructed as people reconstruct their memories of events. The difficulty in dealing with psychological time comes in the necessity of creating connective tissue between scenes so that the work seems to flow smoothly, and the reader does not suspect that the author has made a significant omission. The challenge then becomes selecting the appropriate scenes with which to construct your story.

Through the workshop I learned that it is equally important to describe characters appropriately and to describe characters at the appropriate time. The main character of my original short story, Adam, is described as having a “slim waist, and broad shoulders” this elicited the reaction that the character was too romantic from Dr. White and the rest of the class. My intention in writing the character was to have his external characteristics align with his internal values. My mistake, as an inexperienced writer was in paying so much attention to the physical characteristics of the character the first time that the readers were presented with him. In my rewrite of my short story, I do not describe Adam's physical characteristics. It is not always necessary to do so, particularly in a short story. Rather, I attach the characters in my rewritten short story to specific physical characteristics when necessary. It is impossible for a writer to describe all of the physical characteristics of a place, or setting, without bogging the reader down with irrelevant details. Through workshop discussion I realized that an author must be extremely attentive of the physical characteristics that he does choose to describe. Because only a selection of the physical characteristics of a given scene will be presented, those that are selected are treated by the reader as the characteristics, which in the authors mind, held the greatest importance. This is the reason that such a simply oversight on my part as the author completely misconceived my character in the minds of the readers.

Returning to my metaphor of a chessboard: If a story without narrative or exposition is like chess pieces without a chessboard, a story without a climax is like a chess game that simply stops after a few moves. It is impossible to write a satisfactory story without including a climax to bring the action to a head, and make the grand statement of the story. This was particularly difficult for me as an author because of the ten page limit placed on our stories. At first, I attempted to revise my initial short story, taking the advice of out textbook, and trying not to be the writer who tears entire pages out of his typewriter, and destroys them. However, I found it impossible to rework the original draft of my short story to include a satisfactory climax, and I eventually scrapped my original story. I then asked myself: what do you want to say, and spent time thinking of how I could say it in the most economical form possible. The result is my new short story, a much more satisfactory reading experience.

By participating in workshop, I learned the value of the workshop experience. Our creative writing workshop was a positive group, people just trying to help others make their work better; in such an environment amazing improvements are made. So many different minds, each looking at a work of fiction from a different perspective are capable of invaluable insights and suggestions.