|

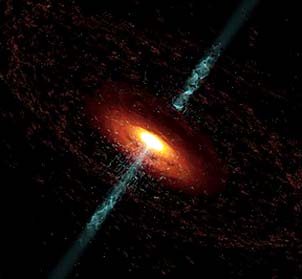

quasar |

LITR 3731 Creative Writing 2009 Final Exam Submissions Essay 1 on fiction |

|

Paul Acevedo

1. Transformations and Viewpoints, the Stuff Fiction is Made of!

I have always been a huge fan of fiction. I love short stories because they are quick and easy to read; anthologies also offer plenty of variety. Novels are great too – they can really flesh out a setting and narrative, drawing me in and keeping me hooked for hundreds of pages. In the past, I have read hundreds of fictional tales without giving their creation much thought. Sure, I may be familiar with many elements of fiction, but I have seldom articulated them. Creative Writing has shown me the components and processes that writers use to create stories.

The process of transformation interests me the most, and not just because I love giant robots. “Transformation refers to basic alterations of events, characters, viewpoints, or settings,” says Stephen Minot (163). This seems like the first step in almost all fiction writing. Writers do not usually stare at a blank page and then create an idea from nowhere; instead, they draw upon their own experiences in some way. But herein lies the difference between fiction and nonfiction: unlike writers of nonfiction, fiction writers must change whatever they draw from into something that suits the story. A nonfiction memoir comes from someone writing about his or her own life, with accuracy being the primary goal. A fictional story contains pieces of the author’s life but is about something else, and entertainment or some other purpose supplants accuracy.

We all have different life experiences, and those in turn help us write unique things. For instance, my short story “Rumble in the ‘Tronics” is about a conflict that takes place within a Target store. Several things that happen to Fred, the main character, have also happened to me. He deals with silly company jargon and customers sidetracking him from his destination. But he’s not me, nor could the main events of the story (consumer electronics coming to life and attacking people) actually happen. I took a bit of truth and transformed it into something ridiculous and fun. Several of my classmates used transformation when they changed fairy tales and myths they read in the past into new, unique stories. Famous authors transform ideas too. “Tori [Amos] lent me a house, and I wrote the first chapter in it, and all she asked in exchange was that I make her a tree,” Neil Gaiman says about writing Stardust (336).

Viewpoint is another important factor that writers must consider. Is a story best served by focusing on a single character’s viewpoint or multiple viewpoints? Utilizing more than one viewpoint allows an author to create thematic depth and ambivalence. Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye explores the effects of racism on several black people in the 1940s; some characters are able to maintain their integrity while others are twisted and dragged down. A single viewpoint tale would usually revolve around a morally good protagonist. But Morrison’s decision to explore multiple perspectives allows her to flesh out the bad characters and their motivations. Multiple perspectives are also great for creating dramatic irony because the author can depict events that some characters will not be aware of without resorting to exposition.

Multiple viewpoints have some downsides, though. Transitions from one character to another can be jarring, interrupting a story’s narrative flow. Following too many characters closely can also confuse or distance the reader. If the author wants readers to care about a story’s characters, he or she must spend sufficient time and effort developing those characters. By sticking to a single perspective, the author can establish one strong relationship with the reader instead of several weaker ones. This holds especially true with short stories – there just is not enough to fully flesh out more than one character in most instances. It is no surprise that all of the stories our class wrote stuck to single viewpoints.

Just as multiple perspectives work well in creating dramatic irony, a single perspective helps maintain suspense. “In fiction, what we as authors withhold from the reader is fully as important as what we reveal” (Minot 190). If the reader only knows what the protagonist knows, the climax will resonate much more. I kept this in mind as I wrote my short story’s conclusion. When Fred leaves the electronics counter to search for weapons, I could have switched my focus to the managers who stayed behind. But because I stayed with Fred’s viewpoint, the fate of the managers is a mystery. This gives the scene of desolation that Fred finds upon his return a greater impact.