|

|

LITR

5831 World / Multicultural Literature: |

|

Hanna

Mak

6

July 2016

Graphic Novels and Immigrant Experience

“How does the medium of the comic strip or graphic novel impact the ways

in which an immigrant’s story is told? How does the narrative vary in relation

to the generation of the storyteller?” I asked, somewhat naively. As it turns

out, the former is not a question that can be answered with brevity, and the

latter question is basically irrelevant within this genre. Almost all of the

comics and graphic novels that I encountered in my research were penned by at

least second generation Americans, and furthermore, their narrative variances

appeared to have been more substantially governed by the developing trends

within the medium itself, in addition to prevailing cultural attitudes of each

era. In hindsight, it seems almost too obvious—who is more likely to author a

graphic novel? Old-fashioned

parents, uncles, and aunties who are busy establishing themselves in a new

country, or their Americanized children? The evolution of the “immigrant comic”

genre is firmly rooted within developments of mainstream American pop culture,

and ultimately caters to the multifaceted desires of its variable audience.

While overall, it tends to speak empathetically to the experiences of the first

generation, its impulses are more often deeply rooted in the “divided” nature of

the second generation, who find themselves toeing the line between tradition and

modernity. Each of these comics attempts to somehow make sense of their

respective authors’ nebulous identities as second-generation Americans, but they

do so in radically different ways, and to equally varied effects.

A unique question that many critics of the immigrant comic genre seem to

continually raise (to varying degrees) is one of “authenticity.” Are the mimetic

qualities of either traditional written immigrant narratives or other graphic

novel genres subjected to equal scrutiny? Could the genre’s place within pop

culture account for this level of analysis and implied skepticism? In his

studies of the graphic novel, critic Stephen E. Tabachnick continually measures

representations of Jewish-American experience with this yardstick of

“authenticity,” appearing to draw upon memories from his own life in order to

lend his personal credence to the graphic novels he studies. In his analysis of

Martin Lemelman’s Two Cents Plain and

Mendel’s Daughter, he cites the

“heavy use of Yiddish” in the character’s speech, as well as a nostalgic list of

familiar cultural artifacts from the 1940s and 50s, that apparently contribute

to his sense of “seeing and hearing a true story” (129, 131).

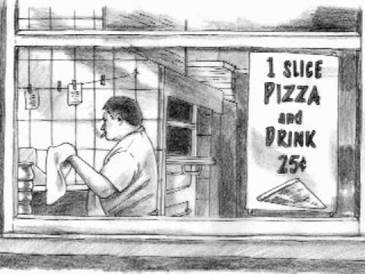

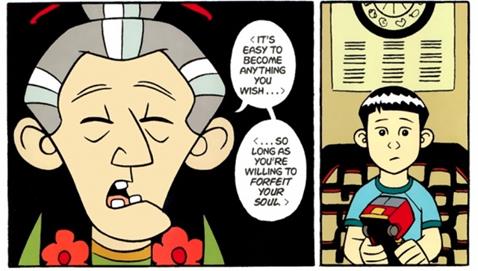

(Above: Example of visual style from the graphic memoir,

Two Cents Plain)

It is

clear that Tabachnick values the narratives of these novels due to their

relationship to his own identity and desire for nostalgia: “As a Jew of

Lemelman’s generation . . . I feel that these could be

my relatives” (132). Beyond measuring

the authenticity of Lemelman’s experience against his own, he offers little

in-depth analysis of the pieces’ content. He affirms Lemelman’s nostalgic truth

as accordant with his own—a fact that is uninteresting in itself. What is far

more interesting, perhaps, is the simple fact that he

believes this insider’s affirmation

is sufficient to recommend the novel to others. This firm belief reflects this

particular graphic narrative’s purpose; the fulfillment of a desire, a

resonant nostalgia in image and in text. The graphic novels’ combination of a

relatively straightforward American Dream storyline with highly realistic,

softly penciled graphics ultimately speaks to the sensibilities of a model

minority who has already “made it” in America. Tabachnick and Lemelman each make

sense of their American success stories through what is familiar to them—the

nostalgic imagery of their childhood days and the culturally pervasive story of

the American Dream.

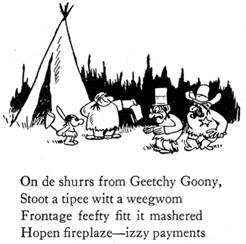

To provide a stark contrast to this, we may examine another

Jewish-American artist—a slapstick and vaudeville-inspired comic writer and

illustrator who achieved immense mainstream popularity in his day, but was (and

still often is) met with marked wariness from his own ethnic community, in part

for the somewhat stereotypical or “low brow” reputation of his dialect humor. In

his parodic body of work from the 1920s and 30s, there is no attempt at

nostalgic reflection. In fact, the comics of Milt Gross were quite conscious in

their creation of a new reality of spoken-aloud in-betweenness, neither wholly

representative of any real Yiddish-speaking culture, nor its dominant culture

counterpart. According to Ari Kelman, Gross’s text “fabricated a kind of unique

English-Jewish speech for a general largely non-Jewish audience,” a dialect that

any American could decipher, but was not spoken anywhere in real life—“a kind of

audible fiction,” that was not meant to be read silently and in privacy, but

spoken (11). Like Lemelman, he was not an immigrant, but a child of immigrants,

and did not speak with their Yiddish “accented tongue,” putting on “the dialect

of his parents as he put on the English of Longfellow or Poe” (13). His silly,

stylized line work lent his visuals much of its mass appeal:

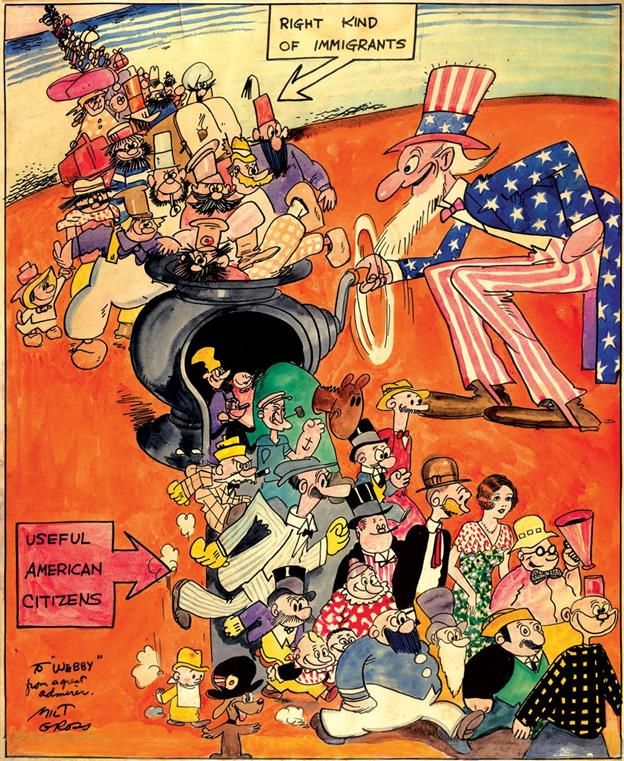

(Above: Panel from “Hiawatta witt no odder poems,” a parody of Longfellow’s

poem, “The Song of Hiawatha”)

While

his cartoons enjoyed massive commercial success among members of the dominant

culture, its dialect humor still included the introduction of Yiddish words into

English malapropisms—thereby creating an extra level to his jokes that only a

Yiddish-speaking New Yorker would be able to fully appreciate. For instance,

Kelman references his use of “shvitzbud” for “switch-board” (15). While the

accent may have simply been funny to general audience members of the dominant

culture, Kelman points out that “shvitzbud” means “steam bath” in Yiddish, which

for immigrant Jews “referred to a public bath, many of which dotted the Lower

East Side.” In Gross’s work, the immigrant experience is navigated somewhat

evasively or indirectly, through humorous word-play, as well as the construction

of an imaginary but shared linguistic space—while his constructed language was

inspired by both Yiddish and English, it could ultimately be understood by all

literate Americans. Perhaps it is unsurprising that such a unique balancing act

of two worlds would be put forward by a second generation American. And yet,

within his community, Gross was typically recognized as a pop culture icon

rather than a distinctly Jewish-American voice (24). In fact, his solitary

mention within a Yiddish newspaper was in a column on “the study of proper

English,” as an example of what not

to do (23). Where many “Ludlow Streeters” considered Yiddish to be a source of

shame or “the lingo of greenhorns,” Gross amplified and distorted these

idiosyncrasies, perhaps somewhat bafflingly, to gain mainstream commercial

success (19).

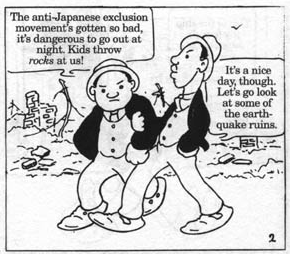

From the example of these two markedly different Jewish-American artists,

it is apparent that the demographic makeup of a comic’s audience, as well as its

specific visual style, is quite revealing of the author’s voice and narrative

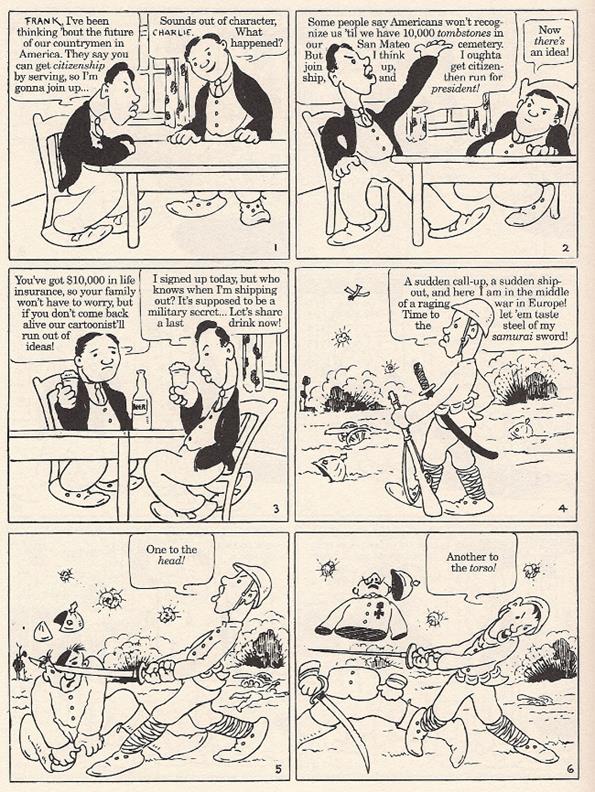

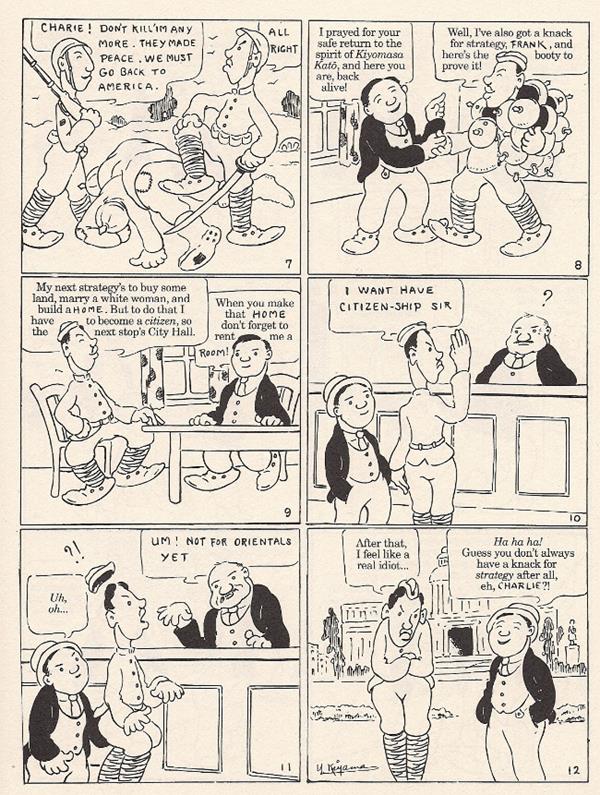

goals. In Henry Yoshitaka Kiyama’s

1930’s autobiographical novel, The Four

Immigrants Manga (which was originally intended as a weekly serial for a

Japanese language newspaper), the four protagonists deal with incidents of

racism and classism, similarly experienced by many Japanese immigrants at that

time (Boatwright 4). Notably, Kiyama’s art is rendered primarily with simple

lines and shapes, with the justification that “When you look at a photo or

realistic drawing of a face, you see it as the face of another. But when you

enter the world of the cartoon, you see yourself” (Boatwright 5). The Japanese

characters also have features and dress similar to Western characters in the

comic, while the Chinese are depicted with slanted slit eyes and buck teeth,

situating the Japanese as Asians who are “modernized in the Western sense” in

opposition to their backward, Chinese counterparts (Boatwright 5).

(Above: A translated panel from Kiyama’s comic. The original was in Japanese)

These

visual and narrative features position the manga as the product of a specific

time, place, and agenda. The comics voice the author’s frustrations

directly to members of his own

community—frustrations that are clearly those of a model minority, as they were

not only unspoken to the dominant culture, but they were also counterbalanced by

the consistently expressed desire to live lawfully, to acculturate, and to

successfully live the American Dream (Boatwright 6).

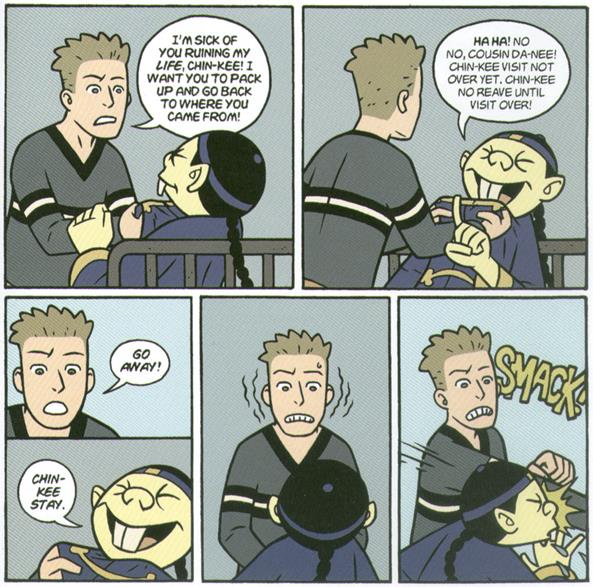

On

the other hand, the contemporary graphic novel,

American Born Chinese, by Gene Luen

Yang, similarly reflects its time and intended audience both in its complex,

modern mode of story-telling and its colorful graphic style, which “includes an

amalgam of Eastern and Western stories and drawing techniques” (Davis 292). The

story is told in three parallel stories that are later “revealed to be parts of

the same whole,” facilitated by magical realism: “the story of Monkey King,

based on the legendary character of the sixteenth-century novel

Journey to the West,”

“Jin Wang, a Chinese American boy” who just wants to fit in, and Danny, “a

blond teenager mortified by yearly visits from his Chinese cousin Chin-Kee, the

embodiment of the Chinese stereotype” (Davis 290). The stories eventually meet,

creatively employing the graphic medium in the unravelling of a

second-generation American’s complexities of identity: Jin Wang meets and learns

from the legendary Monkey King, Danny is Jin Wang’s white alter-ego, and

Chin-Kee is a humiliating stereotype given life. Davis argues that Yang employs

these three storylines to more effectively “explore possible meanings of

Chineseness in the shifting American context” (290). When a young Jin Wang, in

his “struggle to resist the implications of his Chineseness,” tells the

herbalist’s wife that he wants to be a Transformer when he grows up, she speaks

cryptically, foreshadowing his literal transformation into someone else:

Later, he literally becomes someone

else: the white teenager, “Danny, haunted by the (literal) specter of the Asian

stereotype” (280). In this manner, the thrice-divided storyline facilitates the

confrontation and eventual psychological defeat of stereotypes, to “acknowledge,

appropriate and overcome” (292).

Where Lemelman’s graphic memoir appears to most viscerally appeal to other Jews of his generation, Gross’s work was the most appreciated by the dominant culture—albeit with a sly wink and nudge to his fellow Yiddish speakers. Kiyama’s work specifically spoke in Japanese, and was directed towards other, frustrated members of his immigrant community. Yang’s colorful, Disney-like style and coming-of-age identity story expressed a Chinese-American perspective, but deliberately attempted to capture a much wider audience than those merely within his language group. There doesn’t really seem to be much of a distinctive pattern here beyond each author’s own negotiation of their personal American experience, but I suppose there doesn’t have to be. While the immigrant experience has demonstrated certain narrative patterns, it has also been necessarily marked by complexity and diversity; the introduction of literal images only contributes to that complexity, since the images themselves are a text in their own right.

Works

Cited

Boatright, M. D. (2010), Graphic

Journeys: Graphic Novels' Representations of Immigrant Experiences. Journal

of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53: 468–476.

Tabachnick, Stephen E.. Judaic Studies Series:

The Quest for Jewish Belief and Identity

in the Graphic Novel. Tuscaloosa, US: University Alabama Press, 2014.

ProQuest ebrary. Web. 4 July 2016.

Kelman, Ari Y., ed. Goldstein-Goren. Series in American Jewish History:

Is Diss a System? : A Milt Gross Comic

Reader. New York, US: NYU Press, 2010. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 4 July 2016.

Chaney, Michael A.. Wisconsin Studies in Autobiography:

Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on

Autobiography and Graphic Novels. Madison, US: University of Wisconsin

Press, 2011. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 4 July 2016.

Additional Visuals

Milt

Gross Illustration

A

two-page serial from Kiyama’s The Four

Immigrants Manga, pg. 1

Kiyama’s The Four Immigrants Manga,

pg 2

Scenes from American Born Chinese,

depicting Danny (Jin Wang’s white alter-ego), Chin-Kee (the personification of

the negative Chinese stereotype), and the Monkey King: