|

|

LITR 5831 Seminar in World / Multicultural Literature: American Immigrant: model assignments 2014

|

|

Jonathon Anderson

7/1/2014

“Odd and antiquated foreignness”: Cultural Legacies in San Antonio

Campfires

One of the topics of discussion during our consideration of Mexican-American

immigrant stories was the ambiguity of identity that resulted from the ceding of

historically Spanish (later Mexican) territories to the United States. We

contrasted Texas to other border states, observing that the relationship between

cultures is much less contentious than in a state like Arizona. Our speculations

to account for this difference included the possibility that the growing

population of retirees in Arizona is experiencing culture shock because they did

not come from areas of the country that have such long-standing Hispanic

influence and traditions. As I continued to think about this after class, I ran

through a mental list of the names familiar to a kid who grows up in Texas,

paying closer attention to their multicultural roots: Houston, Austin, Dallas,

New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, Schulenburg, El Paso, San Jacinto, San Antonio.

We are as likely to have hot dogs and hamburgers for dinner as fajitas, tacos,

or chili. Driving down Westheimer in Houston, we are as likely to hear Tejano

music as Country music drifting through the open window of an old,

dust-encrusted Ford or Chevrolet pickup. That accordion we hear in Tejano songs?

Thank the German immigrants of the mid-1800s. (This is also reportedly the

origin of the same instrument in Zydeco, according to an

article from the

Houston Institute for Culture.) It’s not for nothing that films depicting the

border states of the Old West (that convergence of the Native American, old

Nueva España, and American Frontier) often show more than the reductive

Cowboy-Indian dichotomy. The chorus of swaggering drawl is likely to include

German or Mexican accents as well.

In many ways, the multifaceted identity of Texas (Spanish colony, Mexican

territory, independent republic, beacon for German immigration, Lone Star State)

is most vividly revealed in the City of San Antonio. Through the end of the 19th

century, the population of San Antonio consisted of roughly equal numbers of

Hispanic, German, and American inhabitants, which resulted in near-ideal

opportunities for the phenomenon we discussed in class of

acculturation, or selective assimilation over time. Although the modern

metropolitan city no longer has that demographic balance (the 2010 Census

reported the population to be 72.6% White, but only 26.6% Non-Hispanic White

according to Wikipedia),

the culture of inclusiveness seems to

remain. Recent

years have seen the addition of events celebrating Japanese pop culture and the

Hindu tradition of Diwali.

Ingredients

A large part of the rugged exoticism of the American Southwest in general, and

of Texas in particular, comes from the superimposition and blending of cultures

over the last three hundred years. The oldest city in Texas, San Antonio was

initially founded in response to the activities of colonists in “New France”

(modern day Louisiana)(Teja 25). The Misión de San Antonio de Valero, eventually

called the Alamo, was built in 1718 with the help of the Payaya Indians who

lived in the area, and by 1731 the “strangely patient courage and zeal of the

old Spanish fathers” had “converted [the Payaya] not only to nominal

Christianity, but to actual hard labor” in order to build four more “ponderous

but rudely splendid” missions (see pictures below) (Teja 26, Olmstead 154).

This was also the time of Spain’s ill-conceived notion to send four hundred

families of “unprepared…Old World peasants [from the Canary Islands]…to populate

[the] hostile Indian frontier,” although only about twelve families had arrived

before the expensive program was scrapped (Teja 27). Relations between the new

Spanish immigrants, called Isleños, and the existing community of colonial

soldiers and assimilated natives was strained by the free reign of privilege

afforded to the Isleños, who had been mythologized as “twelve families of pure

Spanish blood” by the time Frederick Law Olmstead visited San Antonio around one

hundred fifty years later. The small number of what amounted to an aristocracy,

coupled with economic necessity, eventually led to intermarriage between groups,

so that by the eve of the Mexican War of Independence beginning in 1810, San

Antonio’s population was made up “mostly of mixed blood and Indian laborers”

(Teja 28). The families who could trace their ancestry back to the Isleños,

however, persisted in considering themselves Spanish.

Following the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, immigration

policies encouraged settlement of Tejas, which was undertaken largely by United

States citizens, who were struggling with the rising prices of land, and German

citizens, who wanted to escape growing economic problems and overpopulation in

Germany (Oomen). By

1856, the year of Olmstead’s sojourn in the State of Texas, these three groups

(Mexican, American, and German) have established an equilibrium in which they

are experiencing “continuous firsthand contact,” but are remaining mostly

distinct (White).

Olmstead observes, “The singular composite character of the town is palpable at

the entrance” (149). He describes the German houses “of fresh square-cut blocks

of creamy-white limestone, mostly of a single story and humble proportions,” the

Mexican houses, which are “windowless cabins of stakes, plastered with mud and

roofed with river-grass, or ‘tula;’ or low, windowless, but better thatched,

houses of adobes (gray, unburnt bricks),” and the American houses that “stand

back, with galleries…and a garden picket-fence against the walk, or rise, next

door, in three-story brick to respectable city fronts” (150). Giving another

specimen of the “jumble of races, costumes, languages and buildings,” Olmstead

cites the main plaza on Commerce Street, where “American hotels, and new

glass-fronted stores, alternat[e] with sturdy battlemented Spanish walls, and

[are] confronted by the dirty, grim, old stuccoed stone cathedral.” “We have no

city, except, perhaps, New Orleans,” he compares, “that can vie, in point of the

picturesque interest that attaches to odd and antiquated foreignness, with San

Antonio.”

Saddles

This intimacy of ethnic groups, in which “each successive group of

immigrants puts its stamp upon the city, its culture, and architecture,” where

“all mingle, none quite submerging the others,” produces the peculiar

“foreignness” or exotic civic character recorded by Olmstead as well as giving

us an opportunity to see acculturation in action (Texas

State Historical Association, “San Antonio, TX”). We see, for instance,

Olmstead’s delight at the resolution of saddle choice earlier in his narrative

by the discovery of the Texan-style saddle, which, through the “merging of

cultures through prolonged contact,” combines the most useful features of both

the English-style and Mexican-style saddles he had been offered (White,

“Acculturation”). Once in San Antonio, he notices that “the old Mexican wheel of

hewn blocks of wood is still constantly in use, though supplanted, to some

extent, by Yankee wheels, sent in pairs from New York” (Olmstead 162).

The social structure seems fairly clear at first, where capital and government

offices are in the hands of the Americans, skilled labor is in the hands of the

Germans, and transport of goods is in the hands of Mexicans (160). Upon further

acquaintance with the community, however, we begin to see a blurring of groups:

“The variety of [Mexican girls’ complexions] … is naturally referred to three

sources – the old Spanish, the Creole Mexican, and the Indian, with sometimes a

suspicion of Anglo-Saxon [American] or Teuton” (161). As he begins to pay closer

attention to the physical features of the children, he ventures the comment, “we

thought the number of babies of European hair and feature exceeded the native

olive in number.” Here we can see the more relaxed attitude toward ethnic

“purity” in the “mestizo” tradition that grew out of Spanish colonialism, and we

can see the first signs of the inclusive multiculturalism that underpins the

modern city of San Antonio, which has “succeeded in merging its past into the

new in each generation” (TSHA). The result is a city where, despite growing to

become the seventh-largest city in the United States, with approximately 1.4

million residents, “old Spanish walls remain beside modern glass towers, with

rows of Victorian mansions a block away.”

Interestingly, the process of acculturation in San Antonio has maintained its

equilibrium as the world has changed around it. Developers continue to purchase

and repurpose local landmarks, like the

Alamo Quarry Market

on the north side and the old

Pearl Brewery

downtown. Projects like the renovation to the Gonzalez Convention Center take

the opportunity to pay tribute to the city’s heritage while providing aesthetic

and technological updates to the facilities. In 2013, the Bexar County Parks and

Facilities Department launched the

BiblioTech Project,

which is supposed to be the nation’s first bookless library.

Horizons

During my research, several

sidebar questions came up that could be interesting to pursue. The most relevant

to our preoccupations in this seminar is the consideration of the periodic

shifts in San Antonio’s dominant culture, since we talk about assimilation or

acculturation in reference to a dominant culture. Because of the somewhat rapid

sequence of major events before and after Mexico’s aggressive policies to

encourage the population of Tejas, a strange situation was created where the

dominant culture shifted at least two or three times in the span of a generation

or two. I wonder how it might have altered the normal flow of the immigrant

narrative. Another topic that would be interesting to follow up on would be the

cultural attitudes of the three main ethnic groups in 19th century

San Antonio and how they affected the sense of a social contract. Olmstead

spends a little time discussing the apparent disenfranchisement of the Mexican

citizens when the Anglos take over. Olmstead describes the Mexicans being

treated like minorities until their further acquaintance with the new statutes

enables them to apply to the proper bureaucratic channels, after which the

balance is basically restored.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

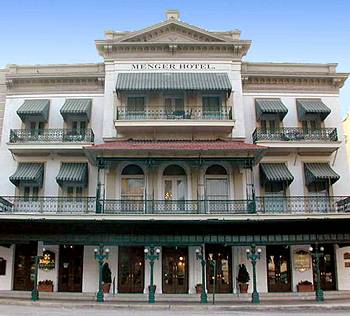

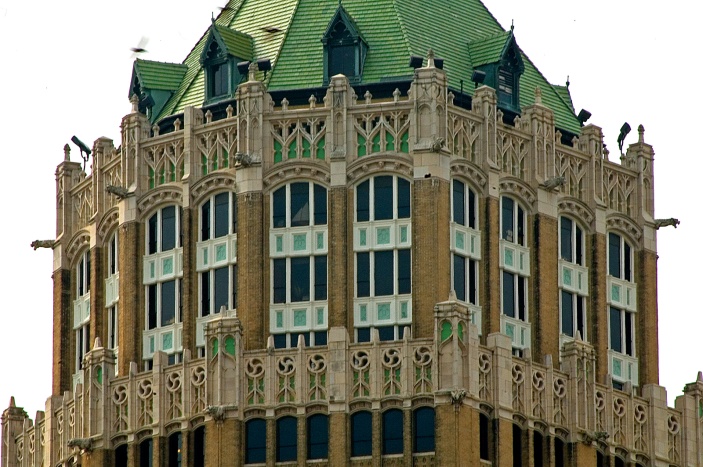

Examples of cultural inclusiveness, accommodation and

incorporation of preexisting heritage

upper right: St. Joseph Catholic Church

Below:

Lila Cockrell

Theatre at Gonzalez Convention Center, Detail of mural

|

|

|

Works Cited

De la Teja, Jesus F. “A Spanish Borderlands Community: San Antonio.”

OAH Magazine of History 14.4 (2000):

25-28. Web. 1 Jun. 2014.

Olmstead, Frederick Law. A Journey

through Texas; or, A Saddle-trip on the South-Western Frontier (1859).

Internet Archive. The Library of

Congress, 16 Dec. 2009. Web. 1 Jul. 2014. <

https://archive.org/details/journeythroughte01olms>