|

|

LITR 5731 Seminar in

Sample Student

research project

Spring Research Journal |

|

Laura A. Moseley

18 April 2010

Literacy and Minority Cultures:

Friend or Foe?

Literacy, in this sense, is not simply reading the word, but

reading the world. And literacy also involves transforming the world; literacy

"becomes a vehicle by which the oppressed are equipped with the necessary tools

to reappropriate their history, culture, and language practices."

(Cutler, “Dismantling “The Master’s House”: Critical Literacy in Harriet

Jacob’s Incident’s in the Life of a Slave

Girl,”209)

Every minority in America has its own reason for learning to

read and write English, and these reasons seem to be linked with how the

minority arrives on American shores.

African Americans, Native Americans and Mexican Americans have had to

decide to what extent they are going to assimilate into the American culture.

This extent of assimilation can be seen through how each minority has

been given access to English language and literacy, and the level at which they

have embraced these learning opportunities.

As we have learned in Objective 5c. of our course objectives, “literacy

[as viewed by minorities] is the primary code of modern existence and a key or

path to empowerment.” I will also

be examining objective three as it relates to each minority group discussed.

Each minority group will be examined individually beginning with the

Africans who were brought to the States as slaves.

I will then look at Native Americans who were on North American land

before the European settlers, and finally, I will discuss literacy and Mexican

Americans who were both colonized like the Indians as well as immigrating like

the Europeans.

Africans, who went on to produce African Americans, did not

come to the States freely; they were abducted, chained and forced to cross the

ocean in the filthy lower decks of cargo ships just like any other form of

livestock. African Americans were

brought to America against their will but once they were arrived, they developed

their own version of the American Dream.

African Americans

3a.

African American alternative narrative:

“The Dream”

("The Dream" resembles but is

not identical to "The American Dream." Whereas the American Dream emphasizes

immediate individual success, "the Dream" factors in setbacks, the need to rise

again, and a quest for group dignity.)

The quest for the African American Dream is strongly

correlated with the African American quest for literacy.

Out of the minority groups that have been mentioned; African Americans,

Native Americans and Mexican Americans; African Americans have embraced literacy

as a means of obtaining a voice to describe the horrors of slavery, the need to

rise above this history, and to obtain dignity even though slavery and racism

is, if not the most, one of the most dehumanizing acts ever conferred from one

human onto another. The African

American grasp for literacy and education began when they, as Africans, were

chained and put into the hold of a ship. This

grasp for literacy was born out of a unique need to learn to communicate not

only with the dominant culture, but also with each other.

Unlike immigrants from other countries, native Africans did not share a

common language and culture among themselves. Each tribe in Africa had unique

customs and languages. As noted by

Olaudah Equiano, one of the few slaves who embraced literacy to the extent that

he was able to write his own story,

From the time I left my own nation I always found somebody

that understood me till I came to the sea coast. The languages of different

nations did not totally differ, nor were they so copious as those of the

Europeans, particularly the English. They were therefore easily learned; and,

while I was journeying thus through Africa, I acquired two or three different

tongues. (Equiano, ch. 2, par. 12)

However, when these slaves found themselves crowded together

in the hold of a slave ship or having to learn to work and survive on a

plantation, it would not have been expedient for everyone to learn several

different ways of communicating.

They had to find a common language and the most sensible one to adopt was the

language of their masters, the language of the dominant culture.

Slaves had very

few opportunities to learn to read and write.

They had no time that was their own as they were either working for their

master or working to take care of their own personal households.

However, around 1750 a Presbyterian minister by the name of Samuel Davies

wanted to teach the slaves in Virginia how to read so that he could convert them

to his form of Christianity:

“Davies as a Presbyterian believed that the attainment of true religion by

anyone, bond or free, black or white, required extensive religious knowledge

that came from not only hearing the word of God but also reading it.”

(Richards, 335)

Davies ran into many

obstacles while trying to save souls and bring literacy to the slaves:

slave owners feared their slaves learning to read; he had limited

resources in the form of books, especially level appropriate materials; Africans

did not share a common language; and he had limited time to spend on teaching

reading when he had seven meetings, or congregations, to preach to.

(Richards,

339)

Arguably for Davies, the largest obstacle on the path of bringing literacy to

the slaves, were the slave holders.

The fear of slave owners towards a literate slave population is consistently

seen throughout slave literature.

As noted in Jeffery H. Richards work on Samuel Davies,

“…why slaveholders thought

literacy a dangerous practice: it threatened to spread beyond their control, and

this breaking of slaves' metaphoric chains of wickedness potentially made human

property more aware of the literal bondage to which they were subject,” (366)

and as stated by Mary Cutler in her article on literacy as seen in the life of

Harriet Jacobs, “…words fight the ideological

system that condoned slavery, because writing challenges the notion that slaves

are sub-human, animals or chattel to be traded.

To write is to move from object to subject…”

(Cutler, 210) Slaveholders

felt they would lose complete control of their property if this property were to

learn to read and become more intolerant of their situation.

If, as a human, you could read and learn of ideas, careers, and pleasures

of which you knew, no matter what you did or how hard you worked, you would

never have access to because you did not even have free access to yourself, how

would you be able to face the next day of jumping at another’s command?

This point is best expressed by Frederick Douglass, who, like Equiano,

made his way to freedom and as a result of his relentless pursuit of learning to

read and write, was able to leave for the generations that followed a narrative

of his life as a slave and his escape to freedom.

The

reading of these documents [various abolitionist papers] enabled me to utter my

thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but

while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more

painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was

led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than

a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and

stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery.

I loathed them as being the meanest as well as the most wicked of men.

(Douglas, ch. 7, par. 9)

Davies, however, did not give much thought to this problem.

He was only concerned with saving the slaves soul and to be saved they

must be able to read.

The female slave

and author Harriet Jacobs also encountered a negative aspect of being literate.

Jacobs’ literacy, which she valued highly, was used to torment and harass

her by her master.

Jacobs’ owner, Dr. Flynt,

had been making inappropriate sexual advances toward her and she had been

pretending that she did not understand the meaning of his coarse and unwelcome

innuendos.

One day he

caught me teaching myself to write. He frowned, as if he was not well pleased;

but I suppose he came to the conclusion that such an accomplishment might help

to advance his favorite scheme. Before long, notes were often slipped into my

hand. I would return them, saying, "I can't read them, sir." "Can't you?" he

replied; "then I must read them to you." He always finished the reading by

asking, "Do you understand?"

(Jacobs, 28-29)

In this instance, the slaveholder actually used the fact that his property was

literate to his advantage. Yet for

all the sexual harassment her reading ability brought on her, Jacobs was still

thankful that she had been able to learn these skills, and she felt it was very

important for her children to get an education as well.

The mistress who taught her had always intimated she would free Jacobs

when she died, however, when the time actually came, Jacobs was not freed.

In fact it was as a result of this mistress’s death that Harriet ended up

in the hands of Dr. Flynt who mentally abused and harassed her until his death.

Despite all of this, she still remembered this mistress fondly because, “While

I was with her, she taught me to read and spell; and for this privilege, which

so rarely falls to the lot of a slave, I bless her memory.”

(Jacobs, 11)

As the slaves

became aware of Samuel Davies literacy program, they began to flock to him in

numbers that he was not prepared for.

He had to rely on donations of books and materials to give to the slaves

so they would have something to take back to their homes to learn from.

Davies thought that the slave holders should provide some materials

because he felt the slaveholders should take some responsibility for the

condition of the souls of their slaves.

When the slave owners did not help with materials, Davies eventually

partnered with SPRK, Society for Promoting Religious Knowledge among the Poor,

and, “As

long as the society provided books, he could carry on the campaign without the

necessity of appealing to slaveowners for assistance.”

(360) SPRK was in

London and would send all of the books and materials

they could, but there was never enough

and most of it was not on the elementary level needed by the slaves who knew

nothing. Davies needed rudimentary

materials like spelling books, yet he was always appreciative of what he

received. SPRK continued to do and

send what it could, ”Though it is certain that the Revolution closed the door to

donations from the SPRK in London, the extent of the society's contributions to

Virginia from 1765 to 1775 is not clear.”

(372) Davies died around

this time as well, so without an advocate and with the loss of donations of

reading materials, the slave literacy program in Virginia ended.

It is even more interesting this program existed in the first place,

since in most slave states it was illegal to teach a slave to read and write.

Samuel Davies

literacy ministry could be compared to that of a missionary in a foreign county.

More than one-third of the blacks in Davies’ program were African born;

they were not African American.

These Africans probably came from an oral society and literacy as we think of it

in America, reading and writing, would have been something totally foreign,

magical and new to them. As noted by

Richards, “Literacy to people without

it would have seemed strange on first encounter.

In their narratives, Olaudah Equiano and James Gronniosaw encounter the

"talking book," a totem that conveys language by some secret, silent, magical

means and spurs both of them to become literate, Equiano enough to write an

eloquent book of his own.” (344)

It is not clear in Richards’

article how this language barrier was overcome, but it was noted,

that more than three hundred potential students of his one thousand black

parishioners had a native language that was not English or a creolized dialect.

In the case of African learners who were adults? particularly those captured as

adults and sold in Virginia? the "Progress" Davies mentioned must have come from

the achievements of individual slaves who developed methods for reaching

Africans. (361-362)

Richards also points out how Davies spent the majority of his

time teaching church doctrine not teaching reading, “Because he believed that

blacks' ability to become literate was equal to that of whites, he imagined that

it was enough to get a few slaves started who would then become teachers of

others.” (361)

Having slaves teach other slaves not only freed Davies to focus on

religious matters, but it possibly answers the ability of the native African

slaves to become literate. African

and African American slaves working and living on the same plantation would have

had to work out some form of understanding to be able to function as a work unit

and to be able to survive the extreme hardships of slavery.

Slaves

themselves had various reasons for learning to read and write.

To some it was the mystery that kept them apart from the dominant

culture, to some education seemed to be what was needed to gain freedom by

either the ability to write one’s own pass or to be able to live as a free

person. As pointed out by Cutler, “Indeed

literacy has been seen as one of the most essential components of the slave

narrative genre and it has often been associated with freedom…”

(Cutler, 210) When

approached by Samuel Davies, the slaves in Virginia realized that, “However

much slaves might have lost in their moves either from Tidewater or equatorial

Africa, they did discover one thing that the new settled minister offered that

they likely never had? the opportunity to decipher the written signs by which

white people governed.” (340-341)

The statement above shows how slaves viewed literacy as an equalizer with

the dominant culture. If they could

attain an education they could possibly find a way out of their horrible

condition. If this was the language

“by which white people governed,” then maybe the slaves could use it, too.

Maybe they could use it to their advantage.

Frederick Douglass realized early in his life as a slave that the key to freedom

was the ability to read and write.

From the time he realized he was a slave, Douglass knew when the time was right,

he would try to escape to the north.

Douglass writes,

“I looked forward to a time at which it would be safe for me to escape.

I was too young to think of doing so

immediately; besides, I wished to learn how to write, as I might have occasion

to write my own pass.”

(Douglass, ch. 7, par. 11) Douglass

was very inventive in his way of reaching his goal of literacy.

He was frequently

at a shipyard and he kept seeing the same letters on the sides of boxes and he

practiced writing them and learning their meaning.

He then used a trick that he would employee throughout his education,

After

that, when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could

write as well as he. The next word would be, "I don't believe you. Let me see

you try it." I would then

make the letters which I had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask him to beat

that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which it is quite

possible I should never have gotten in any other way.

(Douglass, ch. 7, par. 13)

Douglass became adept at tricking school age white boys into

teaching him things and they did not even know that they were doing it.

Samuel Davies was

just one unique individual who wanted to give the gift of literacy to the slaves

in the guise of saving their souls, yet there were so few lives were touched.

Even without an advocate like Davies, slaves like Equiano, Douglass, and

Jacobs found their own path to becoming literate and, “to decipher the signs by

which white people governed.” Henry

Louis Gates, Jr. ponders in the introduction to

The Classic Slave Narratives, “Have

there ever been more curious origins of a literary tradition, especially when we

recall that the slave narrative arose as a response to, and refutiation of,

claims that blacks could not write?”

(3) We are fortunate the

slaves did strive for literacy and freedom so we are able to learn from their

stories today, and to be reminded how we should never take our own freedoms and

choices for granted.

Unlike African Americans who were forced to come to America, Native

Americans did not come to America, they were already here.

They were here before Columbus discovered this continent and then they

were forced off their land, and out of their culture and into a more European

one.

Native Americans

3b.

Native American Indian alternative

narrative:

"Loss and Survival"

(Whereas immigrants

define themselves by leaving the past behind in order to get America, the

Indians once had America but lost it along with many of their people. Yet they

defy the myth of "the vanishing Indian," instead choosing to "survive,"

sometimes in faith that the dominant culture will eventually destroy itself, and

the forests and buffalo will return.)

Like African

Americans, Native Americans are an involuntary minority as defined by Katherine

Hayes. Hayes contends,

“Involuntary minorities include members

of a minority group who have suffered slavery or colonization and who have later

been denied true assimilation. Examples include American Indians,

African-Americans, native Hawaiians, and Mexican-Americans. Generally speaking,

involuntary minorities usually experience greater difficulty in school

adjustment and demonstrate more academic failure than do voluntary minorities.”

(252) Course

objective 3b deals with the Native American Indian alternative narrative of

“Loss and Survival.” This

alternative narrative can clearly be seen in the way that Native Americans have

grappled with the dominant culture’s idea of literacy.

The early education of Native Americans by the dominant culture was

through contract schools that were mostly lead by religious organizations.

An example of a contract school was The Morris School as seen in Wilbert

H. Ahern’s article “Indian Education and Bureaucracy:

The School at Morris, 1887-1909.”

Today, after many failed models of Indian education, it is interesting

that the model is moving back to contract schools, but with a different flavor.

In their article “Changing the Culture of Schooling:

Navajo and Yup’ik Cases,” Jerry Lipka

and Teresa McCarty examine the current movement in Native American education, “…new

federal, tribal, and community initiatives are dramatically transforming

schooling in many indigenous settings. These initiatives include

community-controlled contract and grant schools, increased local control over

state-sponsored schools, and independent "freedom" and cultural survival

schools.” From a literary fiction

perspective, this struggle for the loss and survival of the Indian can

best be shown through the characters of Lipsha Morrissey, Lyman Lamartine, and

King Junior (Howard) Kashpaw in the book

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

As

observed with African Americans, religious organizations played a very important

role in the literacy of Native Americans:

“In 1887 the

various religious denominations still managed 35 percent of the Indian boarding

schools through contracts with the federal government. The Roman Catholic church

educated more Indian students than any other denomination and was responsible

for all federally sponsored Indian schools in Minnesota.”

(Ahern, 84) These schools,

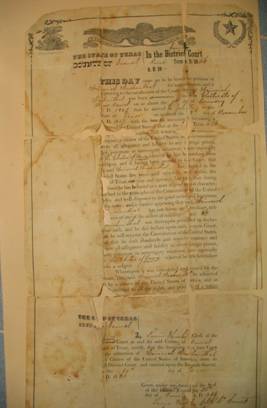

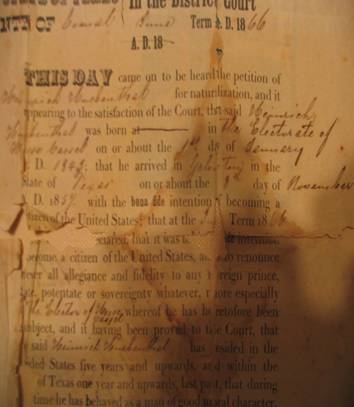

such as the Morris School, drawn below, were not on the reservations so the

children had to travel

(Ahern,

85)

(Ahern,

85)

to them. The idea

of having the Indian children as boarders was as a means of indoctrinating them

into the dominant culture. Ahern

points out the popularly held thought that,

"The schools should be located in the

midst of a farming community, remote from reservations, and in the vicinity of

railroads and some thriving village or city. The students would thus be free

from the great downpull of the camp, and be able to mingle with the civilized

people that surround them, and to participate in their civilization. . . .”

(Ahern, 86) The longer the

children were away from their native culture, the easier it would be to educate

them in the ways of the dominant culture as, ‘“They would be taught the meaning

of citizenship, the importance of work, diligence, and thrift, and the value of

Christian civilization, as well as the academic studies "ordinarily pursued in

similar white schools."’ (86)

Evidence of this form of education and its problems is also pointed out

in Lipka and McCarty’s piece, “Prior to the founding of the Rough Rock

Demonstration School in 1966, most students attended mission or federal boarding

schools. Stories abound of the psychological and physical abuse inflicted on

children at federal schools, as well as the alienation of parents from all

aspects of school life.” (268)

The Federal Government did not necessarily want Native Americans to

assimilate into the dominant culture, but they wanted them to be easier to

handle and the easiest way to change a culture is to start with its youngest

members. Eventually the federal

government abandoned this type of school structure and began building schools

directly on the reservations. These schools were fashioned after regular city

schools, only they were built on the reservations so all of the children

attending were Indians, yet the curriculum and the teachers were of the dominant

culture. This form of education,

however, did not and does not work well for the children because they were and

are still being taught by and about the dominant culture.

Their native ways and their native culture are ignored for the more

standard curriculum taught in non-reservation American schools.

However, there is hope.

Educators are beginning to see, because of high incidents of students

dropping out, that maybe the way and the material being taught to indigenous

populations needs to change. Lipka

and McCarty’s article deals with a new form of minority culture education, a

form of education where the language and the culture of the minority is taken

into consideration.

The experimental school at

Rough Rock departed radically from these experiences. Originated through an

unprecedented contract between the community, a tribal trustee board, and the

federal government, Rough Rock became the first to elect an all-Indian governing

board and the first to teach in and about the native language and culture.

School founders describe Rough Rock's philosophy as a "both-and" approach, in

which children are "exposed to important values and customs of both Navajo

culture and the dominant society, [and] not forced to make an 'either-or'

choice. (268)

The

two experimental schools that they focus on are on a Navajo reservation in Rough

Rock, Arizona and a Yup’ik area in Alaska.

These two education systems were based on “the Hawaii-based Kame-hameha

Early Education Program ( KEEP)” that, “nurtured further pedagogical changes

that encouraged bilingual teachers to view themselves as essential change agents

within the school.” (269)

The students were to be taught by teachers who were part of their

community and the curriculum included their native languages and cultures.

Lipka and McCarty observe, “An example of such an adaptation is a recent

theme study on wind, in which third-grade students examined local and regional

climatology, geography, and Navajo directional symbolism and oral narratives

while maintaining journals and other written records of their work in Navajo and

English.” (270)

If anyone is to learn anything, they must understand and connect with the

person teaching them and with what they are being taught.

There must be a frame of reference and commonality before new material

and ideas can be introduced. If the

children can learn to read and write through materials that are familiar to

them, then they can go on to learn main stream ideas of the dominant culture as

well as anything else they want to know because they will possess the skills

necessary to read and learn for themselves.

Perhaps if Lipsha Morrissey had been able to attend a

reservation school similar to the one described above in the community of Rough

Rock, a school where his heritage and unique talents were respected and

encouraged, he may have stayed in school and learned what he needed from both

cultures, but instead he had to make the best choice for him.

Lipsha was telling his father, Gerry Nanapush, the story of his life, “I

told him all the things about me which I owned up to:

how I had quit school for the betterment of my mental powers, and learned

on my own;…” (364)

Lipsha felt he could not get the

knowledge he needed from the education of the government school.

He knew he had the gift of the “touch” and no amount of learning to read

and write was going to teach him what he felt was important to his life.

There is more than one form of literacy and that is what the dominant

culture needs to realize. As

described in Objective 3b, Lipsha does not want to lose any more of his culture

than he has to. He wants to be able

to pursue and nurture the gift given to him by his ancestors.

Lyman Lamartine, on the other hand took what he could from the

government school. He had a very

different view of literacy from the view of Lipsha Morrissey.

Lyman felt he was able to better the plight of his people due to the fact

he had accepted literacy as defined by the dominant culture and only through

this definition could Native Americans prosper.

Literacy as defined by the dominant culture is to be proficient in

reading and writing the English language.

The dominant culture has enough problems accepting individuals who look

different than they do, but a minority is totally outcast if they also act

differently. Lyman looked back at

all of the things that the dominant culture had done to him and his people and

one of his thoughts was, “They took your kids away and stuffed the English

language in their mouth,” but if he had not been able to read, if he had not

known the English language, if he had not been taken away to school, he would

not have been educated enough to know about how to use laws to the advantage of

his people. (Erdrich, 326)

Lyman felt it was, “…high past time the Indians smartened up and started

using the only leverage they had—federal law.”

(326) The use of the law

would, of course, cause the Native Americans to be assimilated into the dominant

culture, but Lyman thought assimilating was the way to get back at the White

People. In other words, beat them

at their own game.

The ultimate form of assimilation in

Love Medicine can be seen in the

character of King Kashpaw, Junior.

King Junior, who spent limited time on the reservation and lived in the city,

was already able to read when he entered school.

In fact, “The teacher had said to his mother, ‘”Your boy is very bright,

Mrs. Kashpaw. Did you teach him how

to read?” “I don’t know how he

learned it,’ his mother had said.

‘Unless from that TV program.”’ And

that is indeed how little King Junior had learned to read, from watching Sesame

Street on television. Unless it is

McDonalds, there is probably nothing more American than Big Bird, Oscar and the

gang. Many American children,

including myself, learned a tremendous amount from watching Sesame Street and

Mr. Rogers during their formative years.

Also, when given the option, King Junior did not even want to be called

by his legacy, Indian name. The

first day of class the teacher asked, “‘King Howard Kashpaw, Junior,’ said his

new teacher. ‘Which of those names

would you like to be called?’ He

had never thought about it.

‘Howard,’ he was surprised to hear himself answer.

It was that simple. After

that he was Howard at school.”

(330) By virtue of the fact Howard

was light-skinned, from his mother, and his being educated through the

propaganda of the dominant culture as seen on television, Howard became part of

the dominant culture. King Junior

had no interest in his Indian heritage if he ever realized that he possessed it

to begin with.

Native Americans

were on this ground long before Europeans even knew the ground existed, yet they

have been forced to relinquish their way of life to fit into the dominant

culture. As seen in

Love Medicine and the articles by

Ahern, and Lipka and McCarty, the method by which the dominant culture has

chosen to educate them has played a major role in this loss of their culture.

As we shift to

looking at literacy in the Mexican American culture, we will see that they are a

mix of having already been here like the Indians and choosing to come here like

the Europeans immigrants. As a

result of this mix, Mexican Americans can be thought of as “The Ambivalent

Minority” as seen in class objective 3 c. below.

Mexican Americans

3c.

Mexican American narrative: “The Ambivalent Minority”

("Ambivalent" means

having "mixed feelings" or contradictory attitudes. Mexican Americans may

exemplify immigrant culture as individuals or families who come to America for

economic gain but suffer social dislocation. On the other hand, much of Mexico's

historic experience with the USA resembles the experience of the Native

Americans: much of the United States, including Texas, was once Mexico. Does a

Mexican who moves from Juarez to El Paso truly immigrate?)

Some Mexican

Americans are similar to Indians in that they were on American soil first

because it was not American soil yet.

States like Texas, New Mexico, and California were all part of Mexico

before they were taken over by the United States.

The Mexican nationals that lived on this land did not choose to come to

America; they were forced to either move off their land, which was no longer

Mexico, or learn to become part of the dominant culture.

While other Mexican Americans chose, usually because of economic

circumstances, to cross the border into the United States to chase the American

Dream like traditional immigrant cultures.

In her critical work “Attitudes toward Education:

Voluntary and Involuntary Immigrants from the Same Families,” Katherine

G. Hayes raises a very interesting question, “When

does a Mexican become a Mexican-American? When does a voluntary minority become

an involuntary minority?” (254)

The character of Antonio Luna Marez in Rudolfo Anaya’s novel

Bless Me, Ultima is a good example of

these unique Mexican American literacy issues.

Many

Mexican American children are raised with Spanish being the primary language

spoken in their households. As

pointed out by Hayes, “Majority group children come to school equipped with the

language, culture, and values of the school, and minority group children do not.

This has a direct and often negative impact on minority children's school

success.” (Hayes, 251)

In Bless Me, Ultima, Spanish is spoken in the home and Tony and his

siblings do not learn English until they go to school.

Tony speaking of his sister Deborah observes, “She had been to school two

years and she spoke only English.

She was teaching Theresa and half the time I didn’t understand what they were

saying.” (11)

As a first grade student, it is overwhelming enough to walk into a school

room with so many other children you do not know, but to not know the language

spoken by the majority of the other children and of the teacher would multiply

the initial anxiety enormously.

Also, as observed by Tony’s household, after Mexican American children reach a

certain age, they may no longer be able to communicate effectively with others

in their own home.

Hayes

deals with the Ogbu model for minority education in her article.

This model was developed by John Ogbu and,

According to the Ogbu

model, an important factor in determining the school adjustment and academic

performance of minority children is their minority type, voluntary or

involuntary. Voluntary minorities come

from those groups who have moved to the United States in search of greater

economic and educational opportunities.”

(252)

Anthony Marez is an example of both a voluntary and an involuntary immigrant.

His family is originally from Mexico, but moves just across the border to

the city because his mother wants her children to have the advantages she thinks

the city can offer, like education.

Tony’s father, however, was happier in Mexico riding the range and living a less

settled life. Tony’s mother, a

Luna, comes from a very stable family of farmers who are rooted deep into the

soil they work. She has visions of

Tony following in her family’s ways and becoming the next leader of their family

and their community while Tony’s father lives with the dream of heading west to

California. So, part of Tony, the

Luna part, is a voluntary immigrant is being pushed to get an education and

become a scholar; and the other part, the Marez part, wonders if the old ways

are the right ways and should be upheld.

What happens in the case of older children who are forced to migrate

because it is their parents desire to move to America?

Are these young adults voluntary or involuntary immigrants?

What happens to them if they do not want to assimilate?

And in all fairness, they would have the hardest time assimilating

because their formative years would have been spent in another language and

another culture. It has to be hard

for these individuals to get their bearings in their new home.

An

often overlooked group when dealing with the issue of literacy is the adults who

immigrate to create a better life for their family.

These individuals may not have been able to read and write in Spanish

because they were too poor to go to school and they had to work to survive.

The plight of these adults is shown most eloquently in Pat Mora’s poem,

“Senora X No More.”

my

hand and tongue knot, but she guides

and I

dig the tip of my pen into that white.

I

carve my crooked name, and again at night

until

my hand and arm are sore,

I

carve my crooked name,

my

name. (lines 20-25)

As a member of the dominant culture it is hard for me to understand how a person

can live until adulthood and be unable to write their own name.

Some

minorities try to uphold and value the ways of the culture they came from.

As described by Hayes, “Primary cultural differences are those that

existed before any two specific cultural groups came into contact. Voluntary

minorities often continue to practice and maintain their own customs even after

contact.” (253)

Holding onto the old culture can be seen with Tony through the story of

the golden carp. The day school

ended for the summer break, Tony was walking home and he ran into Samuel, a

classmate. Samuel asked Tony to go

fishing. While they were fishing,

Samuel told Tony an old Indian story about the golden carp which was considered

a god to the Indians. The story was

very old and had been handed down to Samuel as a story told orally just as he

was telling it to Tony. The story

was of “the people” who lived in the valley and were told by their gods they

could eat anything but the carp.

These people became hungry and there was nothing left to eat but the carp, so

they ate it and the gods punished them by turning them into the forbidden fish.

One of the gods felt for his people and wanted to be with them so he was

turned into the golden carp and was said to still live in the waters to that

very day. Tony was confused by this

story because it pitted his two worlds against each other, the Catholic world

which is learned through catechism lessons or school, and the world of the

golden carp and the old ways which are passed down from generation to generation

orally. This confusion of his two

worlds continues when Tony finally gets home and tells his mother he has been

promoted two grades and will be in third grade the next year.

Tony’s mother is very happy, “Grande, Deborah, Theresa!

Come quick! Tony had been

promoted two grades! Oh I knew he

would be a man of learning, maybe a priest”

she crossed herself and sobbed as she held me tightly.”

Tony also notes, “Ultima was very happy too.

“This one learns as much in one day as most do in a year,” she smiled.

I wondered if she knew about the golden carp.”

(81) As a member of the

dominant culture it is fun and interesting to learn about other cultures, but we

can always take what we want and walk away.

If you are the member of a minority culture, you cannot walk away, you

have to learn to reconcile and deal with both.

The Mexican American school child is locked between his or her culture at

home which might consist of multiple generations, and with Spanish being the

only language spoken; and the dominant culture where he or she may not be able

to communicate because of the language barrier.

How does this child, at the age of five, leave the only environment he or

she has ever known to enter an environment where they are not the dominant

culture? These children have to

start at that moment reconciling between the ways of the loving family they

trust and the stranger who they share little in common with, not the least of

which is the language.

Katherine Hayes followed a group of Mexican American students who were caught

between these two worlds for a period of time to see how they performed in

school. She interviewed and

observed these students and their parents and noted how the parents did believe

in the “power of education to improve one’s station in life,” and, “They

expressed those beliefs to their children.”

(258) It is very important

for any parent, not just a minority parent, to emphasize the importance of

learning to their children. It is

important for parents to create a welcome, learning environment at home.

Tony’s mother understands the importance of education and wants him to

learn, but for her own reasons, not for his.

His mother begins from his very first day of school preparing him to

become a scholar and a priest.

Tony’s mother exclaims, “An education will make him a scholar, like—like the old

Luna priest.” And his father

retorts, “A scholar already, on his first day of school!”

His mother asserts back, “Yes!”…“You know the signs at his birth were

good. You remember, Grande, you

offered him all the objects of life when he was just a baby, and what did he

choose, the pen and the paper—“

(54) His mother’s lofty

expectations only add to Tony’s confusion about what is the right way with the

world. He realizes as soon as he

enters the school the old ways cannot help him there, and yet he still makes the

choice to work hard and excel.

All

people should strive for some form of communication with each other.

People should also strive to respect each other’s cultures and values.

This is especially true for the dominant American culture, because we

were, and to some extent still are, the New World that others look at as the

land flowing with milk and honey.

We who are members of the dominant culture need to respect the differences in

the minorities around us instead of assuming that everyone should conform to the

way we live. Minority groups should

be given the ability to learn the basics of literacy by whatever method is best

for them and minority cultures should be celebrated and recognized by all.

Works Cited

Ahern, Wilbert H.

“Indian Education and Bureaucracy:

The School at Morris, 1887-1909.”

Minnesota History 49.3 (Fall, 1984):

82-98.

Anaya, Rudolfo. Bless

Me, Ultima. New York:

Grand Central Publishing, 1972.

Cutler, Martha J. “Dismantling "The Master's House": Critical

Literacy in Harriet Jacobs' Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.”

The Johns Hopkins University Press 19.1 (Winter, 1996):

209-225.

Douglass,

Frederick. Selections from, Narrative of the Life of Fredrick Douglass an

American Slave; Written by Himself. Boston: The Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/AfAm/slavenarrs/Douglassed.htm

Equaiano,

Olaudah. Selections from, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah

Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. London, 1789.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/AfAm/slavenarrs/equianonarr.htm

Erdrich, Louise. Love

Medicine. New York:

Harper Perennial, 1993.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, ed.

The Classic Slave Narritives.

New York: Signet Classics,

2002.

Hayes, Katherine G.

“Attitudes toward Education:

Voluntary and Involuntary Immigrants from the Same Families.”

Anthropology & Education Quarterly 23.3 (September, 1992):

250-267.

Lipka, Jerry and Teresa L. McCarty.

“Changing the Culture of Schooling:

Navajo and Yup’ik Cases.”

Anthropology & Education Quarterly 25.3 (September, 1994):

266-284.

Mora, Pat.

Senora X No More.

Online.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/Mexhisp/poems/MoraPSenoraX.htm

Richards, Jeffrey H. “Samuel Davies and the Transatlantic Campaign for Slave Literacy in Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 111.4 (2003): 333-378.