LITR 5731:

Seminar in American Multicultural Literature: Minority

Sample

Student Research Project

Kathleen Walker-Anderson

Literature 5731

The Cherokee Removal: Finding Utopia

Purpose

The purpose of this journal is to act as a starting point for my creative thesis by serving as a gathering of knowledge that influences and inspires the writing of a short story that will be part of a collection. I need to locate several characters within a specific historical context so that they are given an identity, which in turn will give them life within the narrative and shape the narrative itself. The characters I am focusing on are ‘Cherokee Woman’ or ‘Old Woman O’Bryant’, and ‘Hiram O’Bryant’ as a trickster figure due to the oral account of his possible escape from jail. Other characters are touched upon as the necessity arises to expand on my narrative. In relation to my thesis, my intention is to write a collection of short stories that focus on the working class experience across color lines in accordance with my own family history and my own experiences. “Leaving Utopia” is intended to be one story within the collection.

The body of the journal contains the research material I gathered, along with references to how my discoveries and knowledge gathering affected my short story. I am writing this journal in the order I read the texts based on the notes I took while doing the reading. This is a study of my own writing process, which is greatly beneficial to my thesis and improvement of my abilities as I come to understand how I put fiction together. My own experience with writing fiction is limited as the bulk of my creative work has been in the form of poetry and nonfiction prose. The conclusion of this journal will be a new outline incorporating what my research inspired.

Pre-Research Character and Plot Outline

“Leaving Utopia”

The following information contained in this outline is nonfiction so far as written family history documents prove. At this point the plot is limited and sketchy at best. The primary source of the plot comes from court transcripts of the trial of “The State of Texas vs. Hiram O’Brien, Benjamin F. O’Brien, William Felts” concerning the “Murder of the Mitchell Boys, Marion and John Frank Mitchell and Attempted Murder of William A. Mitchell.” For the purpose of fiction I have changed William Felts to James T. Booker O’Bryant, who is my ancestor. The following outline is organized as follows: capital Roman numerals indicate characters, numerals indicate plot, and any information given in parenthesis is fictional based on my own assumptions. The names in this outline are the actual names as taken from family history documentation and will serve as my cast of characters for my narrative. The only discrepancy in the documentation is the spelling of the last name, which switches back and forth between O’Brien and O’Bryant; I have chosen the latter spelling.

I. Duncan O’Bryant

A. Irish protestant immigrant

B. Baptist minister to the Cherokees of South Carolina

II. Wilson O’Bryant

A. Duncan’s younger brother

B. Left Ireland to escape entering the family tradition of being a Catholic priest

III. “Cherokee woman”

A. Wilson O’Bryant’s wife (they meet after he goes to South Carolina to stay with his brother Duncan)

B. full-blooded member of Cherokee tribe

- “Cherokee woman” and Wilson O’Bryant marry and migrate to Utopia, Texas. They have three children.

IV. Three sons

A. Hiram Duncan O’Bryant, eldest

B. Benjamin Franklin O’Bryant

C. James Booker O’Bryant, youngest:

i. known for being married many times and fathering many children. One woman, Florence, has been spoken of in oral history, but no census records or other government documents show proof of her existence. He had a family with Florence while married to his last wife, Nancy Denson without Florence’s or Nancy’s knowledge somehow

ii. Florence had three sons

iii. Nancy had a daughter, Sarlida “Annie” Jane O’Bryant (raised by Hiram Duncan after James’ death); she had two older boys from a previous marriage

iv. Nancy died during the birth of Sarlida. Nancy’s eldest son shoots and kills James Booker O’Bryant blaming him for his mother’s death

- “The Murder Trial of the Mitchell Boys” is based on court transcripts and oral family history. The murders occurred on April 26, 1882. The trial took place in the fall of 1889 in the city of Kerrville, County of Kerr, State of Texas.

- The conflict was over 80 acres of land which was ‘abandoned’ by the Mitchell family for two years while they were working in Austin.

- During their absence Ben O’Bryant settled the land and built a homestead. While Ben was in “Sabinal” for ten days driving home a small herd of cattle he purchased, the Mitchells returned and set up camp on the land.

- Mitchells accused Ben and the O’Bryants of being “squatters” (as overheard and spread through townspeople)

- Ben had legally acquired the land through an abandonment clause.

- Ben, Hiram, and James confront Mitchells at their camp on the land.

- Ben to Marion Mitchell, eldest son, “Get off this land you God damn curly headed son-of-a-bitch”

- William Mitchell, father, responds: “you go away O’Bryant. We want no trouble with you about the land we will let the law settle it.” *Remember, Ben O’Bryant does legally own the land

- Ben says to William: “you damned old red-headed son-of-a-bitch”

- William retorts: “you black son-of-a-bitch”

- A ‘shoot-out’ ensues. Marion, eldest son, and John Frank, middle son, are both killed. William, father, and William Jr, youngest, 15, are injured but survive.

- None of the O’Bryants are shot or even injured.

- The three O’Bryants are arrested and put in jail. The trial takes course over seven years. Hiram O’Bryant supposedly died in jail—he was found guilty post-mortem. Ben and James were also found guilty and sentenced to three years in jail.

- Oral family history has accounts of Hiram fathering a child a year after his supposed death in jail; “a posthumous birth”.

- The law never told the family where Hiram’s remains were buried. He was not buried in the family plot in the Utopia cemetery like the other O’Bryants.

- Ben O’Bryant loses the land to the surviving Mitchell family members, but upon release from jail (served 2 years 7months) Ben and James both are given full pardon and restored to full citizenship.

- Court transcripts mention an “Old Woman O’Bryant” but she never testifies, nor are there many details about her (for the story, I am making Old Woman O’Bryant and Cherokee woman the same person)

Introduction and Brief Background

Before our class discussions of Native American literature during the course of this seminar, my understanding of American Indian identity was very much rooted in the romanticized portrait of the Indian, as it is related to the ideas of the “noble savage” or the “evil Indian.” It is necessary to move beyond such a view in order to create a believable American Indian character that does not fall into the category of either of those extremes. Before beginning the research process for this journal, it was daunting to think about writing an American Indian character because I really did not know much about the history due to the fact that the history is not the single history of the “Indians” as I had been taught or assumed, but very distinct and multiple tribal histories as I have learned.

I chose to focus on the Cherokee Indians after tracing my genealogy back to the Cherokees living in South Carolina before the Trail of Tears. The discovery of my Cherokee ancestry happened last summer and came as a surprise because my own oral family history had always claimed that we were of Apache ancestry. I grew up with a portrait of Geronimo in my home that my mother painted to honor our Apache heritage. The family history I have was compiled by a woman named Virginia Baade and given to me at the O’Bryant/O’Brien family reunion in Utopia, Texas last June.

The Cherokee lineage is traced through my paternal great-grandmother, Katherine Norton Walker, who was of Cherokee Indian ancestry. Katherine Walker is the great-granddaughter of Meley Jane Wofford and Wilson O’Bryant. Meley Jane was half Cherokee. The family tree states that she was the daughter of Nathaniel Wofford and “Cherokee Woman”. The family tree ends with “Cherokee Woman” on the maternal side of Meley Jane, but the lineage of her paternal side, the Woffords, dates back to 1620. The family history of Wilson O’Bryant, her husband, is also extensive, containing the account and court transcripts of the murder trial which is the main plot of my story so far. There is no information given about the Cherokee woman’s history. For the purpose of the story, I have combined Meley Jane and her mother “Cherokee Woman” into the same character. My decision to combine these two real people into one fictional character is mainly due to the desire to work within a specific time period. In reality “Cherokee Woman” died before 1830, while Meley Jane lived from 1801-1875, which is historically the time period that best coincides with critical events in Cherokee history relating to my own narrative. The focus of this journal is a retracing of Cherokee tribal history, especially as it relates to the advent of the white man, and a study of Cherokee literature.

The fact that the ‘white’ branches of the O’Bryant family tree are quite complete, while the Cherokee branch was left to break, or never attached at all, is a strong testament to the fractured history of the American Indian; wherein genetic survival is only as obvious as cultural survival based on many generalities of what it means to be an Indian. “Indian” is a broad term; what it actually means to be Indian in light of the history of American Indians is not simple subject matter. I am experimenting with how Cherokee culture may have survived in my own lineage despite the lack of knowledge of its existence. After all, I do not know for a fact that any of the information I have been provided in relation to my family tree is completely accurate. It is all a matter of interpretation. “Cherokee Woman” will be as real as I make her.

The bulk of the genealogy was gathered through government documents, such as census records and court cases. My assumption was that written records of Cherokee history did not exist or were difficult to find, which would explain the incomplete nature of the O’Bryant family tree. During the course of my research, I learned that the destruction of the Cherokee tribal government in the east, mainly associated with a series of laws passed by the state of Georgia between 1825-1835 with the intention of oppressing the Cherokees, and the devastating effects of “The Trail of Tears,” left Cherokee records scattered and lost. This lends some explanation to the lack of information about “Cherokee woman” on the O’Bryant family tree. My need to discover Cherokee history is due to the fact that there are no family stories that have been passed on to give details about my Cherokee lineage, also compounded by the mistaken information passed down to me that my lineage was Apache. The portrait of Geronimo is not a suitable portrait for the character of “Cherokee Woman” or her half Cherokee sons, Hiram, Benjamin, and James T. Booker O’Bryant. The tendency of the dominant culture to categorize Indians into broad generalities is evident in my mother’s careful artistry of a local legend, which really had nothing to do with the reality of our ancestral background. Apache and Cherokee became synonymous as ‘Indians,’ and the symbol of Geronimo replaced the existence of “Cherokee Woman” until now.

Pre-Research Questions

The questions I formulated before my research, the discoveries I made during the course of this project, and the conclusions I came to in relation to my short story will be referenced according to the organization of the outline. For example, my first question is regarding

I. Duncan O’Bryant, B. Baptist minister to Cherokees of South Carolina:

I, B: What Baptist Missions or Indian Mission Schools existed in the South Carolina area?

II, B: Why was Duncan a Baptist, while family records indicate Wilson left Ireland to escape the priesthood, which indicates Catholicism? Did religious wars at home influence his decision to go to South Carolina to be with his Protestant brother? Why did he run from the priesthood?

III, A: How did Wilson and Cherokee woman meet? What was the role of religion, because Duncan was a minister and Wilson was running from the priesthood, in their meeting?

III, A & B: Who was Cherokee woman? Why was she in the South Carolina area? What was the former territory of the Cherokee tribe? Why did she marry a white man? What was her name? Was it changed from a tribal to a ‘Christian’ name? Did she attend a mission school? What was the role and affect of missions and mission schools among the Cherokees?

IV, A: I want to experiment with Hiram as a trickster figure. Who or what were common trickster figures in Cherokee oral tradition and literature? How do they function? For example, do they subvert “the law”, such as Gerry Nanapush in Love Medicine? Are there common animal symbols for tricksters among the Cherokees? In the literature?

1: What brought Wilson and Cherokee woman to Utopia from South Carolina? It was this migration that set the wheel in motion; a key event that would lead to the confrontation between the Mitchells and the O’Bryants.

2, L & M: Perhaps Hiram didn’t die in jail, but escaped and the ‘representatives of Texas Law’ made up the story of his death to avoid embarrassment. (After all, we must always “let the law settle it” as William Mitchell senior suggests.)

2, F,H & I: What is the source of these insults? They sound like they could be associated with the “Color Code”.

2,P: Why doesn’t Old Woman O’Bryant testify? Is there a deeper explanation such as the Color Code for this?

Research

The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents

Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green

I decided to begin this project with the history of the Cherokee Indians and found that focusing on the removal of the Cherokees would be the most beneficial as the time period coincides with the lives of my ancestors as recorded in the genealogy, approximately 1800-1875. Because the history of the Cherokee removal is so extensive, it is difficult to find and rely on one source of information; however, the inclusion of historical documents in this book gives a variety of perspectives on the historical events. I found this book extremely informative though the authors do have the tendency to paint a biased picture of some events, which I became aware of after reading two books by a Cherokee author who had a completely different perspective. Literature always provides the benefit of a different perspective than history; that is why this particular book was quite effective.

It opens itself up and manages to avoid being a romanticized account of Cherokee history by allowing other voices to have their say. The first half of the book gives an account of the general history of the Cherokees as written by the authors, but the second half is a collection of thirty different written texts ranging from letters, wills, journal entries, memoir excerpts, majority rulings, census records, and treaties; the texts are written by men and women, Cherokee and white. It is the personal accounts as opposed to the drier government documents or court rulings that I found the most useful as it is the details of lived lives and not generalities that are the makings of stories. Because there were so many different texts within this one book, I find it necessary to discuss several of the texts individually as they had the most influence on my narrative. It is beneficial to have a general knowledge of Cherokee history to understand the impact of the removal, so I will begin with excerpts from a brief chronology provided in the back of the book. The importance of the chronology comes back up for discussion later in the journal when I discuss the literature I read.

“Chronology of the Cherokee Removal (c. 1700-2003)

1700 First Cherokee contact with British traders.

1756 French and Indian War

1760 Cherokee War and first invasion of Cherokee towns

1763 The Crown prohibits settlement west of the Appalachians

1776 American Revolution

1783 North Carolina grants Cherokee land to its citizens; Cherokees cede land to Georgia

1785 Treaty of Hopewell

1788 US Constitution ratified

1791 Treaty of Holston, “civilization program”

1793 Invention of cotton gin, deerskins invaluable

1794 Chikamaugas make peace

1800 Moravians establish mission among Cherokees

1802 Compact between US and Georgia regarding Indian land cessions

1808 Cherokees first recorded laws

1808 First major Cherokee migration west of Mississippi

1810 Cherokees outlaw blood vengeance

1813 Creek War, Cherokees fought with US soldiers

1817 American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and Baptist Missionaries arrive

among the Cherokees

1817 Cherokees establish that only the Cherokee National Council has the right to cede land, not

individuals

1817 Cherokees trade eastern land for territory in Arkansas

1821 Sequoyah introduces a Cherokee syllabary

1822 Cherokees establish a supreme court

1826 Georgia asserts state sovereignty over the Cherokee Nation

1827 Cherokee Constitution written

1828 Cherokee Phoenix begins publication

1828 Andrew Jackson elected president

1829 Georgia extends state jurisdiction over Cherokees and nullifies Cherokee law

1829 Jackson announces his removal policy

1830 Indian Removal Act

1830 Georgia outlaws Cherokee national government, requires loyalty oath for white citizens

living within Cherokee Nation, creates Georgia Guard to enforce state law within the

Cherokee Nation

1832 Worcester v. Georgia

1835 Treaty of New Echota

1838 Removal of the Cherokee Nation

1839 Cherokee civil war” (Perdue 187-189)

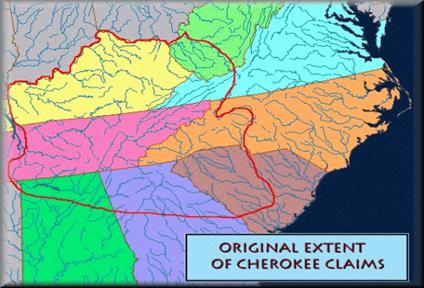

In answer to my question regarding the original Cherokee territory [III, A&B], the Cherokee “homeland” extended from what is now the state of North Carolina into South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama; eventually their domain spread into Kentucky and Virginia (1). The following map shows the original Cherokee territory:

(Martin)

(Martin)

My earlier reference to the authors as biased has to do with two quotes I found at the beginning of the book. The first had to do with the organization of leadership in the Cherokee tribe. “Leadership in a Cherokee community, in fact, rested with a person who could inspire followers rather than someone born to office” (3). This antithesis to a monarchy and ally of democracy seems to border on the notion of the romanticized noble savage and the nostalgia for the ‘old ways’ that were right all along. In reference to the Cherokees’ spiritual beliefs regarding balance in the universe, where if the blood of one clan is shed by another clan, the only way to set the world back in balance is to take blood in revenge, the authors offer this information: “War parties...took care to avoid detection because the object was to return with enemy scalps or captives, not more casualties whose deaths would have to be avenged. This is why the warriors tried to stage surprise attacks and often targeted the easiest victims, including women and children” (3). This account of Cherokee culture threatens to be a characterization of the ‘evil Indian’ or stereotype of the ‘uncivilized savage’. These concepts are only possible however because of the advent of the white man and the concept of voiceless and choiceless that was discussed during the seminar. In the introduction to The Witch of Goingsnake and Other Stories, Chief Wilma P. Mankiller points out that “much has been written about the Cherokee people. Not enough has been written by the Cherokee people” (Conley X).

There are a few original beliefs of the Cherokees, those that were ultimately changed by contact with the white man, that are very important as they come back up several times in some of the texts I read. “While all Cherokees worried about imbalance (disease, drought, and other disasters resulted from imbalance), the individuals most concerned with exacting vengeance were clan members of the deceased” (Perdue 4). This founding belief in maintaining balance is later interpreted by Western civilization as a legal right to murder and condemn. This conflict of cultural beliefs surfaces frequently in the history and the literature.

There were originally seven Cherokee clans within the original territory; and according to the history provided in The Cherokee Removal, “Cherokees believed that the members of a particular clan descended from a distant ancestor and that, therefore, all clan members were relatives” (4). It was also very important for me to discover that, along with a belief in shared ancestry, the Cherokees were originally a matrilineal tribe, “that is, they traced kinship solely through women.” (2). “Children belonged to the clan of their mother, not their father” (4). Though some of the authors’ descriptions border on romantic, such as “The women sang sacred songs while they hoed their corn, and the men observed important rituals, such as asking the deer’s pardon and offering its liver to the fire” (4), the importance of corn and deer hunting is expressed in the Cherokee Origin story and also an explanation of the distant ancestor that unites all the clans:

“the little water beetle created this land out of an endless sea by diving to the bottom and bringing up mud. The great buzzard shaped the mountains and valleys when his wings touched the soft earth. The first man and woman, Kana’ti and Selu, lived on that land. Their son and the unnatural Wild Boy, who had sprung from blood washed off dead game, unwittingly forged the Cherokee way of life when they spied on Kana’ti and Selu. The boys discovered that Kana’ti obtained the family’s meat from a cave he kept covered with a large rock. When they pushed away the rock and accidentally released the animals, they condemned all future generations of Cherokee men to have to hunt for game. Then they found that Selu produced corn and beans by rubbing her stomach and armpits. They decided that she was a witch and that they must kill her. Realizing what her son and Wild Boy intended to do, Selu instructed them to clear a circle and drag her body over the cleared ground seven times. Where her blood dropped, corn grew. The boys tired of their task, however, and they cleared seven little spots instead of a circle and dragged Selu’s body over them only two times. Therefore, corn grows in only a few places, and Indian women must hoe their corn twice.” (1-2).

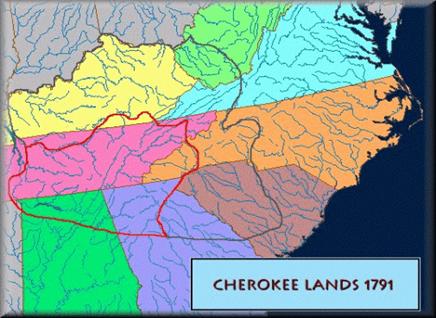

The Cherokee origin story was related very similarly in much of the literature I read. It explains the importance of hunting and farming, and also assigns gender roles to those means of sustenance. The importance of the origin story takes on greater meaning after understanding the history of European contact with the Cherokees. Contact with British traders in 1700 changed the course of Cherokee life forever. “British traders traveled into the Cherokee country for two major commodities—deerskins and war captives” (5). In 1756, the Cherokees entered the French and Indian war on the side of the British. Indian tribes were used as warriors “in their colonial rivalries” (7). During the course of the French and Indian war and afterwards due to attacks “on Cherokees by white frontiersman,” and the failure of the Proclamation of 1763 to stop the invasion of white settlers; the Cherokees came to regard the colonists as the enemy and not “the Crown.” This led the Cherokees to side with the British during the American Revolution. By the time the Chickamaugas, a clan of Cherokees, lost in 1794, the Cherokees had surrendered “more than twenty thousand miles of their domain” (6-7). The following map shows the loss of territory after contact with the British in 1700:

(Martin)

(Martin)

The Treaty of Holston, signed in July 1791, is considered the beginning of the “civilization program” for the Cherokee Indians. An excerpt from the treaty shows that assimilation of the Cherokee was the end goal for federal policy: “That the Cherokee nation may be led to a greater degree of civilization, and to become herdsman and cultivators, instead of remaining in a state of hunters, the United States will, from time to time, furnish gratuitously the said nation with useful implements of husbandry” (11). This policy was set in motion by George Washington and his secretary of war Henry Knox after the establishment of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. The policies that the government enacted toward the Indians before the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 had been considered “’expansion with honor,’ the central premise of which was that the United States Indian policy should make expansion possible without detriment to the Indians” (10). Despite the desire to expand without detriment, it was virtually impossible to do so as the results of acculturation can sometimes destroy the traditions of the past. The Treaty of Holston which sought to change the Cherokee from hunter to farmer had that sort of destructive effect. Thus, the Origin story is told often to recall the traditional ways of the Cherokee, as a means of survival, and perhaps, resistance to the imposition of European ways.

The “Last Will and Testament of Young Wolf, 1814” is an example of what became of some members of a tribe who relied on the hunting of deer by the men and the farming of corn by the women, after the extensive loss of hunting ground along with the introduction of the “civilization” program and European cultural traditions. The first Cherokee laws were recorded in 1808, which “established a national police force to prevent horse stealing and to protect the property of widows and orphans. In particular, the law enabled men to bequeath their wealth to their wives and children in defiance of the matrilineal tradition” (Perdue 14). In 1810 the Cherokee tradition of blood vengeance was outlawed, in accordance with the European definition of civilization. The Cherokees found it necessary to take on many of the legislative and governmental practices of the whites, including establishing a tribal supreme court in 1822, as a means of proving their own civilization and right to sovereignty.

The will of Young Wolf was written in 1814 and clearly indicates a change from the matrilineal tradition which was caused by European influence. If he had kept the Cherokee tradition his land should have gone to his sister’s children, but instead he writes, “Also I leave to my son Dennis my house & plantation & all the farming tools” (Perdue 30). Within this one statement is evidence of acculturation and loss of tradition. Farming had traditionally been done by the women and hunting was done by the men. The transition to and acculturation of farming, ranching, and herding by many Cherokees was possible due to the traditions their economy had been rooted in versus an overall desire to assimilate to the white man’s ways. “Since the common method of herding was to release cattle and hogs into the forest to forage for food, the labor pattern for herding was not much different from that for hunting: Men simply rounded up their animals and drove them to market rather than killing them and taking their skins to traders” (28).

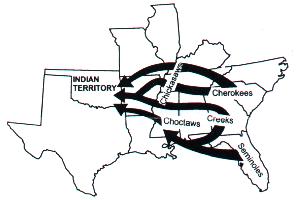

The fact that Young Wolf has a will is a result of the clashing of cultures and the importance placed on property as influenced by European/American ideology. “The very first written Cherokee law focused on the protection of private property” (28). The selling of tribal property to the United States by individuals was severely punished by the Cherokee tribe as most still considered the land communal property. Doublehead, a Chief of one of the Cherokee villages, was killed by Major Ridge, another Cherokee Chief, for selling land to the federal government. The cession of land, before the Cherokee’s established a law to limit that right to the Cherokee National Council in 1817, was usually ceded by those who decided that removal to the west was best. Two groups went west under these conditions before the final removal in 1838. The first left between 1808 and 1810, the second left in 1817. The territory that was granted to these first waves of Cherokees, approximately 4000 people, is shown (129):

(Martin)

(Martin)

In 1817, the National Council also passed a law revoking the Cherokee citizenship of anyone who chose to go west (27). The result of these events was to create a Cherokee tribe already in the West prior to the forced removal in 1838, which was now denied membership in the Cherokee Nation as a whole. The dispossession of land and division of the Cherokee tribe began before The Trail of Tears and continued afterwards with the Cherokee civil war in 1839 in Oklahoma, which was influenced by these earlier migrations and disputes over beliefs in property rights.

The female Cherokee voice is shared in several petitions written and presented to the National Council by women’s councils in 1817 and 1818 regarding the cession of Cherokee land. The discovery of these documents was very important to the character of “Cherokee woman.” The language of these two texts comprises elements of the matrilineal tradition. In a petition written on May 2 1817, a group of Cherokee women express their opinion on the matter of removal: “We do not wish to go to an unknown country [to] which we have understood some or our children wish to go over the Mississippi, but this act of our children would be like destroying our mothers. Your mothers, sisters ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our land. We say ours. You are our descendants; take pity on our request” (132). I attributed the fact that there is no record of “Cherokee woman’s” name to the destruction of tribal records in the east before removal to the west. These two documents gave me a different perspective. Though Nancy Ward, a well known “War Woman” among the Cherokees, is given credit for authorship, the documents use the plural pronoun ‘We’ and are not individually or collectively signed. Because of matrilineal tradition, the women of the tribe are collectively the mother of the tribe, thus the need for individual recognition among them was not necessary. Matrilineal tradition must also be important to “Cherokee woman.” In reference to a name for her character, I have noticed that most women, within historical documents and literature, have English names only, while the men sometimes have two, English and Cherokee.

After researching the history of the Cherokee removal up to this point, some answers to my questions began to take shape. It is apparent so far that the history of the Cherokee Indians is the history of their forced removal. The maps are very important to give a visual reference point to the integral role that the loss of land played in Cherokee history. The loss of the land was ultimately the loss of their way of life.

III, A & B: Who was Cherokee woman? Why was she in the South Carolina area? What was the former territory of the Cherokee tribe? Why did she marry a white man?

Cherokee woman was in the South Carolina area because it was part of Cherokee territory before the cession of land began in 1783. She was born between 1801 and 1803 according to records, which means she was born before the first migration of Cherokees west of the Mississippi in 1808. Wilson and Cherokee woman did not leave South Carolina until the late 1830’s, which means they could have been affected by the forced removal. The fact that the Cherokees were traditionally matrilineal though it began to change with the first recorded laws of 1808, makes it possible that Cherokee woman decided to marry a white man because she knew her children would be Cherokee even though their father was white; because lineage is traced through the mother. If your mother is Cherokee, you are Cherokee.

The transition of the Cherokee economy from one dependent on hunting to one dependent on farming or herding could also lend some explanation to her choice to marry Wilson O’Bryant. It is evident from family records that Wilson was a farmer and a rancher, which he passed on to his sons. In my outline, section 2B states, ‘During their absence Ben O’Bryant settled the land and built a homestead. While Ben was in “Sabinal” for ten days driving home a small herd of cattle he purchased, the Mitchells returned and set up camp on the land.’ Cherokee woman may have decided to marry a man who could farm and ranch because that is what many of her people had been forced to do; after the Treaty of Holston in 1791, a series of other agreements and invasions by white settlers led to the eventual loss of most of their land which destroyed their hunting economy.

III, A & B: Who was Cherokee woman? What was her name? Was it changed from a tribal to a ‘Christian’ name? Did she attend a mission school? What was the role and affect of missions and mission schools among the Cherokees?

III, A: How did Wilson and Cherokee woman meet? What was the role of religion, because Duncan was a minister and Wilson was running from the priesthood, in their meeting?

The history of the role of missions and protestant religions in the culture of the Cherokees is a history of assimilation and resistance. The Cherokees gave the Moravians, “Protestant German immigrants who had established a town at Salem, North Carolina,” permission to establish a mission in 1800 because they wanted a school “but expressed no interest in the gospel” (12). In 1817, the Presbyterians and Congregationalists arrived, and by 1822, the Baptists and Methodists had established missions also. In a letter written by John Ridge in 1836 he states, “There [are] about 8 churches, where the gospel is preached on sabbath days within the Nation. They are missionary stations supported by moravians, Presbyterians, Baptists, and methodists and each of these churches have a goodly number of pious & exemplary members” (41). The importance of this statement and its implications requires further explanation of John Ridge’s role in Cherokee history along with further examination of the role of missions in the Cherokee removal.

To understand the complex politics that were taking place up to the Cherokee removal in 1838, it is necessary to examine the conflict between the Cherokees and the state of Georgia. My focus switched from South Carolina to Georgia at this point in my research, as the defining events in Cherokee history took place during the conflict between Georgia and the Cherokees over Cherokee territory. Georgia’s assertion of state sovereignty over the Cherokee Nation in 1826 was the result of what Georgia saw as a failure of the compact of 1802 with the United States. The United States had not acquired all the territory held by the Indians as it had promised, according to Georgia. After the establishment of the Cherokee Constitution in 1827, which “defined the borders of the Nation and in legal language proclaimed its sovereignty” (72); the state of Georgia “passed a series of laws beginning in 1828 that subjected the Cherokees to Georgia law” (73).

Despite petitioning President Andrew Jackson for protection in 1829, the Indian Removal Act was signed on May 30, 1830 (121). The federal ruling in favor of the Cherokees in Worcester v. Georgia in March 1832, in which Chief Justice Marshall proclaimed, “The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia have no force” (83); the Cherokees were still subjected to various ploys to force them off their land. The land lotteries of Georgia, which served to allow white settlers onto tribal land, began shortly after the Supreme Court decision in favor of the Cherokee Nation. “Male residents of the state as well as widows and orphans registered for land lotteries...Surveyors partitioned the land into plots and prepared plats, or maps, for each of these plots. Lottery officials pulled a name out of one hopper and a plat out of another; thereby matching winner and prize” (92). It was measures such as this that caused a split within the Cherokee Nation regarding removal; and the roles of Major and John Ridge, and John Ross come into light.

After the migration west of the small group of Cherokees in 1817, most of the remaining opposed removal west. Over the course of the following decade, once anti-removal, affluent leaders Major Ridge and his son John Ridge changed their position on removal. They were the ring leaders of the signing of the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 that ultimately led to removal. In 1833 a law authorizing the confiscation of the land reserves accepted by the “leadership class” of Cherokees “under the treaties of 1817 and 1819” shook the foundation of the Cherokee tribe (84-85). The very “civilization” programs that served to bring this “leadership class” of plantation owners into being by assimilating them to white society was used against them. Think of the will of Young Wolf who leaves his plantation and farming tools to his son to carry on in the European/American tradition.

This law of 1833 confiscated the lands of many influential Cherokee leaders including John Ross, John Ridge, and Major Ridge. The Ridges changed their position on removal and decided the best thing was to go west. The Treaty of New Echota was an agreement to go west and was signed without Principal Chief John Ross’s knowledge. It was ratified by the senate in 1836, and removal was scheduled to begin in the spring of 1838. In June of 1838, about 2000 people were “rounded-up,” placed in stockades and forced west under the supervision of United States soldiers. The journey proved deadly and the Cherokees were granted permission to supervise their own removal which began in August of 1838 when the first of thirteen detachments under John Ross left the east from “Rattlesnake Springs” and the last arrived in Oklahoma in late March of 1839. It is estimated that anywhere from 4000 to 8000 people died on The Trail of Tears (167-168).

(Martin)

(Martin)

The descriptions in John Ridge’s letter of a Cherokee people assimilating to Christian beliefs give clues to the role and affect of missions among the Cherokees. But an understanding of the evangelical movement and the role of religion in the “civilization” program helps give a better picture. “In many northern congregations, attention turned to social ills and the need for reform. This northern evangelicalism inspired the missionaries who came to the Cherokee Nation to establish churches and schools” (94). In general, Christian missions were responsible for “civilizing” the Indians and were subsidized by the U.S. government for that purpose. Christianization equaled civilization. Missions set up schools and also served as training grounds for farming practices. Statistically, it seems that Cherokees welcomed an English education, but by 1835, only ten percent of the population actually belonged to the church (45). The importance of land to the Cherokees is not erased by a Christian education. In a letter written by a Cherokee student, Nancy Reese, on December 25, 1828, she says, “I have been talking to the children about it and one says ‘if the white people want more land let them go back to the country they came from,’ another says ‘they have got more land than they use, what do they want to get ours for?’ (50).

In “Reflections on Removal” written in 1993, Chief Wilma Mankiller describes the reunion of the fragmented Cherokee tribe in 1984 at Red Clay, Tennessee. During removal, some Cherokees “escaped to the mountains and remained in hiding. Those people formed the nucleus of the Eastern Band of Cherokees, now living on the Qualla Reservation in North Carolina” (185). The Cherokees were split into three different tribes according to the cession of land: the first Cherokees to leave for the West, those that left on The Trail of Tears, and those that escaped removal and stayed in the east.

I, B: What Baptist Missions or Indian Mission Schools existed in the South Carolina area?

The Trail of Tears is a defining event in the history of the Cherokee Indians. It would be impossible to write a Cherokee character without reference to the Trail. I have decided to set a portion of the story on the Trail itself. Because Duncan O’Bryant was a Baptist minister, I have chosen him to be the link between his brother, Wilson O’Bryant, and Cherokee woman. My decision to do this was inspired by a series of journal entries written on the Trail of Tears between May and December of 1838. The entries were written by Evan Jones, a “Baptist missionary, who worked among the Cherokees in North Carolina accompanied his congregation to the stockades and on the westward trek” (170).

It is also important to note that the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Worcester v Georgia was Samuel Austin Worcester. He was a missionary who was arrested along with ten others in 1831 after Georgia’s series of laws in 1830, one of which required that all white citizens living within the Cherokee Nation take a loyalty oath, which the missionaries refused. Though religion served as a means of assimilating the Cherokees, many of the missionaries were strong advocates for the Cherokees against removal to the west. This could be another explanation as to Duncan and Wilson’s role among the Cherokees as advocates against removal, which would also further explain Cherokee woman’s choice to marry a white man. The Cherokees accepted whites, as long as the whites accepted them. It goes back to the traditional beliefs surrounding balance and imbalance.

The Witch of Goingsnake and Other Stories

Robert J. Conley

IV, A: I want to experiment with Hiram as a trickster figure. Who or what were common trickster figures in Cherokee oral tradition and literature? How do they function? For example, do they subvert “the law”, such as Gerry Nanapush in Love Medicine? Are there common animal symbols for tricksters among the Cherokees? In the literature?

Robert J. Conley is a Cherokee author who was born in Cushing, Oklahoma in 1940. He received his Masters in English from Midwestern University in 1968. He has had over seventy books published and served as Assistant Programs Manager for the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma (“Robert J. Conley”). I read two other texts for this journal, but chose to include only Conley’s work. The other two texts were pieces of juvenile literature and I decided it was more important to include a contemporary Cherokee point of view. The majority of my research has been of a historical nature, so a contemporary voice is a beneficial inclusion because my narrative will be written from my own contemporary point of view.

In the introduction to this collection of short stories based on Cherokee oral tradition Conley states, “Someone once said of the Cherokee people that you can find Cherokees who will say that they don’t use Cherokee medicine, but you can’t find a Cherokee who will say ‘I don’t believe in it’” (xiv). This statement reminds me of the historical statistics concerning conversion to Christianity. Although missionaries had been among the Cherokees since 1800, only 10% had converted by 1835. In my opinion, the Cherokees were more prone to syncretism, than complete conversion.

The collection begins with a short story titled “Yellow Bird: An Imaginary Autobiography” which is a recounting of the Cherokee Origin story in great detail and a chronology of Cherokee history from the character Yellow Bird’s point of view. The statement made by Conley and the inclusion of an actual chronology of Cherokee history within a narrative is a testament to the resistance of the Cherokee to the white man’s invasion and attempted erasure of the Cherokee people. The fact is that the Cherokees did assimilate in many ways, such as transitioning from a hunting to a farming economy and allowing, often welcoming, the English instruction of their children; yet they still resisted religion, and resisted leaving their land.

Yellow Bird was born in Georgia in 1827 and is the grandson of John Ridge, who, from his deathbed, relates the story of his life. He states that “When I was born, I was given two names—John Rollin Ridge and Tsisqua Dahlonageh” (4). In the majority of Conley’s short stories in this collection, the men have two names while the women have one English name. Among the animal figures in this story are the buzzard and the water beetle, “Dayunisi,” from the Origin story, along with rattlesnakes and copperheads which appear in a story about “Thunder” (who was formerly Kanati before returning to the “Sky Vault”) and the tests he puts his son through to determine that the boy is actually his son. From the chronology in this story I also learned that the Cherokees called the white man “ayonega, or yonegs, ‘white people’” (16).

Among several important historical events he talks about the surrender of the Chickamaugas in 1794, which sent a group of Cherokees to Texas under the rule of Chief Bowl. He also talks about the “Treaty Party” which was the name given to the signers of the Treaty of New Echota. He also references the land lotteries, the Trail of Tears, and the execution of Tsali, who was one of the Cherokees who escaped to the mountains during the forced removal (17-25). Most interesting about this story is the description of the execution of Major and John Ridge after the Cherokee arrival in Oklahoma in 1839. He alludes to the law of 1817 which made it punishable by death for anyone other than the National Council to cede land. By signing the Treaty of New Echota without John Ross’s knowledge they were breaking this law; Yellow Bird concludes that John Ross and his men murdered his father and grandfather. The story is told from Yellow Bird’s deathbed after migrating to California. “The white men of California were, in my mind, John Ross, Andrew Jackson, Wilson Lumpkin [governor of Georgia], and all the red-necks of Georgia and Ross men of the Cherokee Nation” (32). The split that occurred in the Cherokee tribe during the years that led up to the removal is apparent in the literature of this author. The Cherokees’ historical relationship with the law was one wrought with broken promises and political ploys to confiscate their territory. The history of this relationship is evident in these short stories, especially the trickster stories.

“Wili Woyi” and “The Hanging of Mose Miller” were both stories whose main characters were trickster figures. Wili Woyi means “Billy Pigeon” in English. Birds seem to have a special significance within this Cherokee author’s literature. The most significant are the buzzard from the origin story, along with the name Pigeon; and the role of the owl in “Wili Woyi” and the hawk in “The Hanging of Mose Miller” in which the men can put their souls “into the body of something else” (60). Another common thread among the two stories which seems to be related to trickster figures is the use of tobacco in sacred ceremonies that allow their souls into the bodies of birds, or in the case of Wili Woyu, also makes him invisible. The name given for tobacco is “tsola gayundi” and Wili Woyu repeats a charm seven times to make the spell effective (43). In both stories the men are being pursued by the government for murder, namely U.S marshals. The murders however were committed in fairness according to the Cherokee tradition of blood vengeance, and in the opinion of the characters, the murders are the business of the Cherokee tribe, not the white man.

2, L & M: Perhaps Hiram didn’t die in jail, but escaped and the ‘representatives of Texas Law’ made up the story of his death to avoid embarrassment. (After all, we must always “let the law settle it” as William Mitchell senior suggests.)

The Cherokee trickster always gets away from the law even if he has to escape death. In the case of Wili Woyi, he goes with the marshal, Glen Colvert, willingly; but escapes, then escapes again when Colvert comes back with more men to pursue him. In the end, the law is so exasperated with the perpetual escape of this man that Colvert’s superior identifies the dead body of another man as Bill Pigeon, or Wili Woyi. “’We been after this son of a bitch for going on six years now, Glenn,’ said Moss Berman, his voice still low, ‘and I got a damn good record as a lawman, and all I get on Bill Pigeon from you is a bunch of hoodoo stories’” (66). When Mose Miller is hung for the murder of a white man, the executioner swears “’He was dead before he fell,’ said High Pockets. Then he looked off in the direction the hawk had flown. ‘At least I think he was’” (85). These two stories seem to validate the idea that Hiram probably did escape from jail and the lawmen with “a damn good record” covered up the escape by claiming he died in jail. This storyline does lend itself to making Hiram’s character a trickster figure.

Mountain Windsong: A Novel of the Trail of Tears

Robert J. Conley

2, F,H & I: What is the source of these insults? They sound like they could be associated with the “Color Code”.

2,P: Why doesn’t Old Woman O’Bryant testify? Is there a deeper explanation such as the Color Code for this?

This novel is a story of the Trail of Tears as told from a variety of voices. The storyteller, or representative of Cherokee Oral tradition, is the grandfather who throughout the course of the book teaches his grandson the traditional ways of the Cherokees, such as making a blowgun, while relating the story of the Trail of Tears. The grandfather also tells several side-stories that serve to inform his grandson of the Cherokee history, such as the original organization of the Cherokees into seven clans that were each ruled by a “War Chief” and a “Peace Chief” (8). He also tells his grandson of the “Anti-Cherokee laws” passed by Georgia which among other things made it so that Cherokees couldn’t testify (23). The novel takes place on the Qualla Reservation which the Eastern Band of Cherokees was granted after some Cherokees escaped forced removal.

The story of the Cherokee removal is told through the love story of Oconeechee and Waguli, or Whippoorwill, who are separated during the removal. Contained within the narrative itself are actual historical documents including letters and notices from the Cherokee tribe during the years prior to removal. It also includes a complete copy of the Treaty of New Echota signed in 1835. What I found most interesting about both pieces of literature I read, was that relation to the law permeates the history of the Cherokees, and subsequently permeates the oral tradition, which has an affect on the literature.

The importance of oral tradition is symbolized in this novel by the relationship the grandson has to his grandfather. The grandfather will not call the grandson by his name, LeRoy. Instead he calls him “chooj” which is the Cherokee term for boy. Throughout the novel, the boy must initiate the telling of the stories by expressing a desire to hear them. The boy also learns after watching his grandfather perform traditional Cherokee activities and not knowing what his grandfather is doing that “if I just watched and listened and did what he told me I would eventually figure it out” (69). I believe this statement is a testament to the importance placed on oral tradition; and the necessity to recall the entire history of the Cherokee tribe for contemporary readers in general, as the oral necessarily becomes written as a means of survival. Whereas the history that I read often painted John Ross as a hero, and the Ridges as traitors, Conley makes a great effort to paint them as human. Both sides, the followers of Ross and the followers of Ridge, were inevitably caught up in a battle they could not have won considering the general sentiment regarding the ideas of “civilized whites” and “uncivilized savages” in combination with the political wars over federal and state rights in which the Cherokees became a pawn, especially after the election of Andrew Jackson. It was Jackson’s election that helped change federal policy toward the Indians from benevolent to malicious because of his politics which were oriented around the Color Code due to the American slavery system.

This novel also contains a retelling of the ancient Cherokee belief that the west is the “Darkening Place.” Because the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, the west was believed to be “the direction of the color black...the direction of despair” (104). According to Cherokee tradition, the west held nothing for them. This ancient belief is almost proved by the white man’s confiscation of their land and the forced removal west to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears. The advent of the white man changed the Cherokee destiny. In the novel, at the meeting at Red Clay, which was the last meeting with John Ross before the signing of the Treaty at New Echota without his knowledge, a warning is given by an “old-fashioned Indian” dressed in the traditional breechclout and deerskin leggings that “the only way to be saved” is to cast off the white man’s ways and go back to being Cherokees. Among the things to cast off he mentions “cattle and pigs and cats” (36). I found the mention of cats several times in Conley’s work as symbols of the white world. It reminded me of all the cats at Moses Pillager’s in Love Medicine, and the cat-like qualities that are ascribed to his trickster character.

The warning from this old-fashioned Indian is juxtaposed with the appearance of Principal Chief John Ross, elected to the National Council in 1828 after the Cherokee Constitution was written, who is dressed like a white man at the meeting in his “suit with fancy lace” (30); it is obvious that the warning has come too late. The fact that the “Color Code” played a role in Cherokee history is evident in the history of the Cherokee Removal and in the examples given above. John Ross and John Ridge both became quite assimilated to the white world, but in light of the general attitudes toward what was considered “civilized” by white standards they didn’t really have a choice if they wanted their people to have a chance to survive. In the end, the Color Code won and the Cherokees were forced off their land, though Andrew Jackson claimed it was all for their survival. Historical and literary accounts paint both Ridge and Ross as either traitors out for political gain or as men with the welfare of the Cherokee people at heart. The division of the Cherokee tribe was the final result of all these historical events and accounts, and this fact can’t help but become an underlying theme in Cherokee history and literature.

Conclusion

I learned a great deal from this project; and I do actually now feel that I could write a good story with the information I have found. The research has served to inspire the creation of many details and some much needed plot in my narrative. I am rewriting only those portions of the outline that were greatly changed by my research.

III. “Cherokee Woman”

- Known among her people as “Smiling Cat”

- She is of the Red-Tail Hawk clan, known for hunting birds (I found the names of the seven clans on a website and now I can’t find it again); for this reason her village admires the skill of the ‘bird-hunting’ cat; she got her name because of her skill and cat-like hunting ability when she was little (even though she was a girl)

- She is married originally to a Cherokee warrior from her clan who is killed during one of the many invasions by white settlers who tried but failed to take their village by force

- A Baptist mission is built near her village in 1825, a year after her husband’s death.

- She has one son from this marriage. He is four-years-old in 1825 (he will later become Hiram the trickster figure).

- Smiling Cat meets Wilson O’Bryant after attending the mission school to learn English as she feels that the old ways are dying out; she must learn the new if she is to survive

- Her English name becomes Cate O’Bryant after marrying Wilson in 1827. She does not have a conflict marrying a white man as matrilineal tradition guarantees that her children will be Cherokee.

- Because some Cherokee traditions are sustained, the matrilineal tradition of land inheritance is still honored by her clan. Because land allotments of tribal land to individuals had already begun, her uncle, her mother’s brother, had an allotment of land and a small farm which she inherits.

- Wilson and Cate move onto the land but lose their land in the land lotteries that begin in 1832. They were forced off the land by white settlers and left without a fight.

- Wilson and Cate leave Cherokee territory on The Trail of Tears in 1838 with their three sons ages 17, 10, and 7; but break off from the others in Little Rock, Arkansas. Wilson decides to go to Texas. Kate agrees because of the Legend of Chief Bowl and the Chickamaugas who fought to save their land to the bitter end, until leaving for Texas in 1794. She finds strength in Cherokee legends and ancient beliefs. She makes the decision to break off from her people and follow her white husband out of weariness with the course of events, especially distrust of the white man’s word. After all, the west is the “Darkening Place” and she does not know what waits at the end of the Trail. The death and misery she has seen so far do not offer much hope. She finds solace in the fact that her children will be Cherokee and she will teach them the ways of the Cherokee even though they must live in a white man’s world.

I chose the name Smiling Cat for several reasons. The use of the cat as a symbol for the white world inspired me to use this name, along with the personal significance that cats have to me. It bothered me that I was unable to find very many female Indian names when most of the men had both Cherokee and English names, so I decided to give Cherokee woman two names. She is a matriarchal figure from a traditionally matrilineal culture. Her ‘Indian’ name is made up of an animal that wouldn’t exist if European culture had not invaded North America; but it fits her because she is caught between two worlds.

I. Duncan O’Bryant

- Baptist minister who came to Cherokee territory

- He helped to establish the mission that was built near “Smiling Cat’s” village in 1825

- He gave her the name Cate, because of its similarity to cat, after she began attending the mission school to learn English

- He accompanies his congregation on the Trail of Tears after attempting through written appeals and letters to stop the forced removal of the Cherokees. He left Ireland after converting to Protestantism and being disowned by his Catholic family. His own religious struggles make him sympathetic toward the Cherokee plight, though ultimately his underlying motivations are those of the evangelical movement to convert the world to Christianity.

II. Wilson O’Bryant

- Younger brother of Duncan

- Arrives at the mission in 1826 after fleeing Ireland to avoid entering the priesthood. Unlike his brother, his fleeing did not have anything to do with converting to Protestantism or any other religion. He has a strong faith in God and basic Christian beliefs only because he is raised with them, but does not have the desire to devote himself to God like his brother. He comes to the mission because he has nowhere else to go. He is a wanderer.

- Because Duncan and Wilson come from a tenant-farmer family, their knowledge of farming practices fits into the government subsidized civilization programs. It is Wilson’s knowledge of farming that gains him room and board employment from his brother in exchange for helping Duncan teach the Cherokees to farm.

- Wilson meets Smiling Cat/Cate while working at the mission

- Wilson is fascinated with Cate and with the Cherokee culture. He adapts openly to many of their beliefs to the dismay of Duncan, who is intent on converting the Indians to Christianity to ensure their survival. Wilson never becomes wholly Cherokee; he is just different from the white men Cate has seen (the attacking white settlers, or missionaries such as Duncan); which makes the relationship between them possible. She is in a state of transition, with the knowledge that she must change in many ways if she is to hang onto the old ways at all.

IV,A. Hiram Duncan O’Bryant

· Son of Smiling Cat and a Cherokee warrior (I have not decided on a name yet)

· Hiram’s Cherokee name is Little Hawk, but Wilson decides to change it to Hiram Duncan after marrying Cate and adopting him

· Hiram, Ben, and James (the sons ages 17,10, and 7) are all greatly affected by the events surrounding the Cherokee removal, but because Hiram is the eldest, his feelings of revenge toward the white man regarding the events, such as the family’s loss of land in the land lotteries, are even stronger than his brothers

· His father was a warrior turned member of the Cherokee national police force before his death, and he believed in seeing out the Cherokee tradition of blood vengeance, and ensuring the protection of tribal lands from the white settlers

· Hiram’s and his brothers’ strong convictions over the ownership of land were formed during the experiences of their childhood, and continued even after leaving the Trail of their childhood and adolescence into their adulthood in Texas

· Hiram maintains a keen interest in traditional Cherokee customs and pays close attention to everything his mother tells him and teaches him about the Cherokee ways, even after the family settles in Utopia, Texas

“Leaving Utopia,” the story of the murder of the Mitchell Boys:

This journal began as a way to write “Leaving Utopia;” however, I found that I have outlined a different story from my original idea. The above outline serves as a foundation story for Leaving Utopia. The motivation behind murdering two men for 80 acres of land is built up over the course of the story of Smiling Cat and Wilson’s migration to Utopia. Hiram’s, Ben’s, and James’ experiences in their adulthood are a separate story. The foundation for the conflict that led to the murder of the Mitchell Boys is rooted in the experiences of the boys’ parents during the Cherokee removal and the family’s strong conviction over the ownership of land once they finally secure it in Utopia after losing everything in the east.

I also found that though my outline seems to focus on many specific historical events, I want to stay away from references to key figures, such as Ross or the Ridges. My goal is to focus on the details of lived lives, not the generalities of history even though historical context will naturally serve as a backdrop. The fact that the story will focus on loss and survival lends itself to the overall working class theme of the collection if I work it right. I am taking Fiction Writing next semester and I plan to use the outline this journal helped me to create to complete the story. I will then begin the research for Leaving Utopia.

Works Cited

Conley, Robert J. Mountain Windsong: A Novel of the Trail of Tears. 1st ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Conley, Robert J.. The Witch of Goingsnake and Other Stories. 1st ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Martin, Ken. "Historical Maps." History of the Cherokee--Cherokee Maps. 1996. University of Georgia. 3 Dec 2007 <http://cherokeehistory.com/map1.html>.

Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents. 2nd ed. Boston: Bedford, 2005.

"Robert J. Conley." NativeWiki. 23 August 2007. Storytellers: Native American Authors online. 3 Dec 2007 <http://www.nativewiki.org/Robert_J._Conley>.

![]()