LITR 5731: Seminar in

American Multicultural Literature

Student Research Project

Roxane Richter

Religious Syncretism in American Minorities:

Assimilation, Survival or Bartered Devotion?

This topic pertains to religious syncretism and cultural secrecy in American minorities. My theory is that a subordinate culture will try in many ways – through direct conflict, deception, assimilation or syncretism – to have their native religious traditions and culture “survive” the onslaught of the dominant culture’s powerful & sometimes forced adaptations.

But as we’ve see in some of the course’s pieces of literature, especially in Black Elk Speaks and Bless Me, Ultima, the subordinate culture will adopt many assimilated and enigmatic forms of behaviors (often unfamiliar to the dominant culture) in order to co-exist in a threatening or oppressive environment. For instance, they can choose to (outwardly) adopt the dominant culture’s religion, while (inwardly) serving their native religious traditions and gods. Or they can choose to have their religious traditions “survive” via syncretism – by merging their traditional beliefs with those of the dominant society.

In my opinion, coerced syncretic religious behavior, made under duress (threat of physical harm, loss of livelihood, etc.), can be considered “bartered devotion,” in that it is an attempt by the subordinate minority to maintain or attain certain desired provisions by acquiescing to the dominant culture’s demands. This acquiescence can stretch across an extensive gamut of behaviors – from a sham of a thinly veiled societal façade, to a sincere amalgamation of beliefs, to a total revision of values, and so on.

Even in the absence of direct threats, there are virtual (and literal) mountains of reasons for a subordinate culture to try and climb up the proverbial ‘ladder of success’ of the dominant society. In Race and Ethnic Relations, the author explains that subordinate groups crave the “fullest opportunity for participation in the life of the larger society with a view to uncoerced incorporation into that society” (pg. 57). But minority groups are “rarely completely absorbed into dominant group,” totally relinquishing their culture and physical identity (pg 57). So syncretism is a way for minorities to pursue required and/or desired provisions while maintaining (some portion) of their cultural identity. And as minorities attain higher degrees of assimilation in a dominant culture, they can attain entrance into institutions and social cliques, plus achieve decreased levels of prejudice, discrimination, and value and power conflicts, according to Marger (pg. 113).

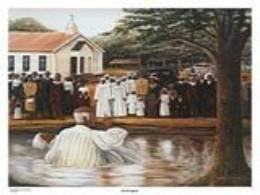

Let us now review how African slaves dealt with living in an oppressive environment, yet still retained their ability to re-ignite their native religious traditions and merge them with New World beliefs.

The African

Diaspora

Slavery forced the dispersion of

Africans to the New World (mainly North America, South America and the

Caribbean). An estimated half million Africans were brought to the United States

over the course of 200 years. But

while the slave trade caused the loss of family ties, and innumerable social and

economic hardships, Africans clung to their religious beliefs and traditions.

But under such extreme oppression, African slaves were forced to reshape

and reform some of their traditions in order to have them survive at all.

Slaves

could deceive their white masters by leading their social lives in the way that

whites deemed fit on the surface, but then expressing their inner beliefs in

ways that whites were not able to detect or comprehend. We read a probable

example of this in Jupiter Hammon’s poem, “An Evening Thought,” where the

slave writes how God’s grace is granted (equitably) to “every one” and

“every Nation.” He ignites religious fervor and (presumably) emboldens slave

to action by writing: “Now is the Day, excepted Time” and “Awake Ye, Every

Nation.” These double-entendre religious writings used a vehicle of the white

dominant culture – Christian hymns and poems –as a safe means of

communicating a sense of African alliance/allegiance, while surreptitiously

strategizing an insurrection.

Another example can be found in

Christian services. White masters did not allow the slaves to play drums, so

they substituted handclapping and foot stomping in order to retain and evoke the

atmosphere of their religious practices. This practice can be found in many

African-American churches today.

In large part, African spirituality was altered, often via syncretism,

with traditions of the slaves' masters, and yet still able to grab many native

religious “footholds” in other religions (like Catholic’s celebration of

saints and votive offerings). Let’s

now explore some of these altered – syncretic – religions.

Examples of Syncretic Religions

With certainty, it would prove an

impossible task to list all minority-led syncretic religions found in America

today in this brief research piece, so I have only focused on some of the more

prominent faiths as examples and provided extremely condensed summaries. (Unless

otherwise noted, the following “Syncretic Religion’s” research was derived

and summarized from Wikipedia and/or the religious organization’s Website.)

The Yoruba culture of Nigeria,

Benin and neighboring areas greatly influenced African religion. The major faith

found among the Yoruba people is called Ifa, which is actually a name for God,

(a.k.a. Olorun or Olodumare).

Orishas are the deities worshipped in the Ifa movement.

q

Santeria

This movement evolved mainly in

Cuba and is now found throughout the Americas, especially in large metropolitan

and immigrant-laden areas such as Los Angeles, Miami and New York City. The

religion is perhaps most well known for its ritual sacrifice of animals (mainly

chickens), but is relatively similar to other Ifa traditions.

q

Kongo

In the Congo, Zaire and Angola,

the Bantu people began what’s practiced mainly in areas of Brazil and Cuba as

Kongo, but is also known as Palo Monte, Palo Mayombe, Xango (Shango), Quimbanda,

Umbanda, etc.

q

Rastafarianism

Rasta, or the Rastafari

movement, is a religious movement that believes Haile Selassie, a former

Ethiopian emperor, is God incarnate. The

term “Rastafari” comes from “Ras (Duke) Tafari Makonnen,” the

pre-coronation name of the emperor. Today there are over one million Rastafari,

including some 5-10% of Jamaicans. Most

Rastafarians are vegetarians and live by the dietary code found in the Bible’s

Old Testament books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy.

q

Voodoo

Perhaps the most notorious

movement of African spirituality in the New World is Vodou, also known as Vodun,

Voodoo or Vodoun. Vodun is practiced in Benin, Dominican Republic, Ghana,

Haiti, Togo and areas in the US - largely where Haitian refuges have settled.

There is a syncretism between African gods and Catholic saints in the system of

Voodoo, so slaves in areas like New Orleans practiced Voodoo, blending Catholic

and African religious rites and practices.

The most well known Voodoo

priestess was Marie Laveau, who was among the first people to publicly mix

African traditions of voodoo and Catholicism, as she herself was a Roman

Catholic. For example, she brought Catholic sainthood into Voodoo ceremonies, as

she created St. Peter Papa LaBas, who is a Voodoo trickster god of the

crossroads. There were also other Voodoo-created saints, like St. Marron (the

patron saint of swamps where runaway slaves would live together).

Much like a Catholic ceremony, Marie Laveau used candles, a statue of the

Virgin Mary and incense, but also food offerings, and a caged snake, on her

Voodoo altar.

For example, the freed and

enslaved blacks would participate in the public

Congo Square dances, but the “real” traditional and magic-laden

Voodoo celebrations would be held in private at Marie’s home. This is another

example of how slaves learned to keep their traditions alive under the

constraints of their white masters.

The Gullah

The Sea Islands of the South are

a chain of small islands off the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Today the Sea Islands retain a predominantly African American population that

has developed a distinctive culture and dialect known as Gullah or Geechee.

Ronald Dasie, a Gullah translator

and author of Reminiscences of Sea

Island Heritage: Legacy of Freedman on St. Helena Island, writes:

" Today, Gullah denotes a way of life for a peculiar and special group of

African Americans who have maintained the purest forms of African mores in this

country... Gullah bonds its speakers with others of the African Diaspora.

About 90 percent of the vocabulary is English, but the grammatical and

intonational features are largely West African. Our West African forebears

skillfully developed Gullah as a communication system effective enough to make

themselves understood in a strange land where even their talking drums were

prohibited…They've maintained their African-born speech patterns and customs

because the un-bridged waterways isolated them from the mainland for years"

(pg 3).

It’s interesting to note that plantation owners in the Gullah region built Christian “Praise Houses” as a means of social control. The Praise Houses, however, provided a meeting place for the slaves’ spiritual guidance and group leadership. Their religion, a blend of both the ideologies of the Baptist Church and African heritage, remains as the very basis of Gullah culture, according to Daise – so much so that the Gullah express time in terms of before or after they "had sense" (i.e. the completion of the Praise House). Gullah’s still use many traditional West African beliefs – such as “the shout,” a counter-clockwise handclapping and foot stomping dance, and superstitious beliefs (graveyards are located near water to ensure that spirits will travel back to African ancestors; and broken dishes, shells and shiny objects are placed on graves to prevent the dead from returning for their personal belongings, etc.).

Bahai’

Faith

The Bahai believe in a prophet named Bahaullah who they consider as a

successor to Muhammed. Followers

recognize Jesus, Moses, Buddha and Zoroaster and other prophets as well, making

it a truly syncretic faith. But

many Bahai’ would reject this notion, because they feel that their revelation

is supreme over previous ones. They

also have their own unique laws and writings that overule all other religious

belief systems.

Candomble’

Candomble’ is practiced mainly in Barzil, and many followers have not

only African, but also European, lineage. The

religion was originally used by the slaves and banned by the Catholic church,

but somehow it has survived over four centuries. In recent surveys, according to

Wikipedia, about 2 million Barzilians (1.5% of the population) have declared

Candomble’ as their religion.

Candomble’ was influenced by Catholic “irmandades”

(brotherhoods) of Brazilian slaves that were organized by the Catholic church in

the 18th and 19th centuries.

These groups were organized along ethnic languages, in order to allow

preaching in the slaves’ native tongues.

This, in fact, backfired, and proved to be a good “cover” for slave

reunions, and may even have aided the religion’s establishment.

Apparently,

Candomblé adroitly moves between Christainity and combinations of African and

Native American gods. Christian

crosses are displayed in temples, and African gods are likened to Catholic

saints. Based on some historical accounts, Christian devotional altars were

used in early slave houses to hide African icons and ritual objects, and

Candomblé dances (in honor of Catholic saints) was used as subterfuge and to

avoid any direct confrontation.

Native American Spirituality

African and African-derived religions bear remarkable similarities with Native American religions and Shamanism. Shamanism, for instance, is a spirituality using magic and an ecstatic trance state to heal and control fire, wind or magical flight, according to Dance of the Deer Foundation. Like other African-derived religions and Catholicism, the shaman makes use of spirit helpers and altered states of consciousness (somewhat akin to Christianity’s speaking in tongues).

But overall, what may be most striking and interesting

to note among Native American religions is that there seems to be very little

evidence of exclusivity, individuality or doctrinal superiority in their

religious syncretism. You certainly get the feeling that Native Americans

(particularly) move comfortably between and among various religious faiths and

belief systems.

Tribal

History in Christian Hymns

The

syncretism of religions can have wonderful, but novel and unanticipated, “side

effects.” For instance, the newly

created literature, songs and poems can serve to “preserve” ancient, native

stories, myths and culture.

In

The Jesus Road, the authors write how Christian hymns sung in the Kiowa

language provided a reservoir of tribal history for the Kiowa Comanche Apache

Indians (pg. 81). But the hymns

also “transmitted power to singers and listeners by connecting them with Kiowa

who have died and whom the Kiowa believe to be more holy or ‘Godly’ than

people in the present” (p. 81). In

the hymns, God is “thickly robed” as Daw Kee (a Kiowa name for Jehovah) and

Jesus appears as Daw Kee's son, but they contain no trace of Christian ethics or

nature of the universe tales.

In Black Elk Speaks, we see the ease with which Black Elk (rather unquestioningly) accepts that the great Christian Wanekia (Savior) is “really the son of the Great Spirit,” and would appear to the Indians next time, and Black Elk even thought the white man’s Wanekia was a red man he had seen in a vision (pg. 181 & 190).

In “Black Elk and the Jesuits,” Enochs explains how the Lakota Indians’ views of rituals, helper spirits, justification and salvation were similar to Catholic beliefs, and “the Jesuits used these similarities to draw the Lakotas into the Catholic faith” (pg. 283). Some examples include:

q

Helper spirit

(Lakota) or guardian Angel/ Mother Mary (Catholics) to give assistance & to

whom they could pray;

q

Atonement for misdeeds (Lakota); Penance for sins (Catholics);

q

Rituals ordered and channeled sacred power and made it usable;

q

Prayers &

ceremonies (done by living)

impact destiny of dead;

q

Road to salvation

is through works and faith; and

q

Sacrifice was key to both – a flesh and blood in the Sun Dance; Christ as a

sacrifice.

Native Americans assimilated many of the faiths and traditions that surrounded them – much like Mexican-Americans, who also utilized both their native and New World beliefs simultaneously. We see strong examples of this syncretism in Rudolfo Ananya’s novel, Bless Me, Ultima, which we’ll review next.

Mexican-American Syncretism

Hispanic syncretism in Catholicism can be seen early on in the story of the Virgin of Guadeloupe, in that the brown-skinned Virgin appears to a poor, common Aztec peasant, Juan Diego, in 1531 (Anthology of American Literature). The poor peasant was canonized as a saint in 2002 for receiving the vision of the Virgin and facilitating, according to Pope John Paul II, the “fruitful meeting of two worlds” and the “catalyst for a new Mexican identity” (New York Times, August 2002, Bruni). The Pope also presented Diego as a model of integration of differing traditions: “In accepting the Christian message without forgoing his indigenous identity, Juan Diego discovered the profound truth of the new humanity, in which we are all called to be children of God,” according to the New York Times article.

But syncretism can also be found in Mexican-American literature. For instance, in Ananya’s novel, Bless Me, Ultima, we follow the lives of recent Mexican immigrants living in New Mexico. We see glimpses of religious syncretism through Ultima, a curandera, one who cures with herbs and magic. Ultima is revered, but oftentimes socially rejected, and is sometimes even referred to as a witch. But she seemingly ignores the outside world, effortlessly gliding from one religion to another, taking the “best of both worlds” to make her powerful magic.

For instance, we see Ultima’s healing of a fever through her blending American and curandera ointments and medicaments, using “Vicks and her many herbs” (pg. 712). The author also uses liberal references to the Holy Trinity in the use of the number three: the three sisters who attacked Antonio’s uncle (pg.88), the three clay voodoo-like dolls (pg. 101), the three bundles to burn in the fire in order to release a curse (pg. 232), and Antonio’s three brothers, which he sees in his visions (pg. 234).

In the U.S. today, one of every seven people in the country identify themselves as Hispanic, which accounts for about half of the country’s growth since 2000 – that’s 41 million people of Latin American and Caribbean origin, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. So clearly the syncretic effect of such a huge migration of Hispanic culture on U.S. religious movements has yet to be fully understood or calculated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, one of the most compelling reasons behind syncretism is a minority’s wish to gain acceptance, provisions, power and equity in the dominant culture. Plus, when you realize that many religions – typically outside the Muslim and Christian order – do not view their religious faiths as mutually exclusive, it’s reasonable that they could accept and envelop new ideologies. This can, in and of itself, provide a compelling reason behind many minorities’ liberal dosage of baptisms and mass exodus to Christian-led beliefs. Indeed, polytheist religions and multi-ethnic regions seem to have a more “naturally inclusive” nature than the centralized, strongly monotheistic religions of the Old World.

So in the end, syncretism may well be a well-flexed double-edged sword: While it allows the subordinate culture to survive under the often-harsh environment of the dominant group, it also serves to relentlessly alter and excise valuable indigenous traditions from its cultural system.

Works Cited

q

Bruni, Frank

and Ginger Thompson, “Bolstering Faith of Indians, Pope Gives Mexico a

Saint,” New York Times, August 1, 2002.

q

Daise, Ronald, Reminiscences

of Sea Island Heritage: Legacy of Freedman on St. Helena Island,

Sandlapper Publishing, 1998.

q

The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity, and Indian

Hymns, Lincoln and London: University of

Nebraska Press, 2002.

q

Marger, Martin, Race

and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives, Wadworth/Thomson

Learning, 2003.

q

U.S. Census

Bureau, www.census.gov, 2000.

q

Wikipedia, “Syncrectic Religions,” www.wikipedia.com.

###