|

|

LITR 5731 Seminar in

Sample Student

research project Fall

|

|

Matthew Martin

1 December 2012

The Black Page

Author’s

Introduction

This story has a rather interesting history. Over this past

summer, I found a copy of Brian Wilson’s autobiography,

Wouldn’t It Be Nice.

I have always been fascinated with his story and his eccentric and perfectionist

way of approaching music (which has earned him the worthy title of “Rock n’

Roll’s Beethoven”).

I had known of his tumultuous relationship with his

father, but after reading his book, I gained a new respect for the man for

having to endure the kind of childhood (or life, rather) that he had. He was

blessed with a natural talent for music, and it seemed his father was jealous of

his son and his gift. Sadly, he would be physically violent with Brian and one

of his father’s beatings cost him the hearing in one of his ears. I kept that

situation in my mind because I’m also fascinated by people who can play an

instrument naturally, like Mozart or Chopin. Those kinds of happenings make for

a good story.

In case it’s not apparent from

the story, I love music. I do play the piano, but I cannot play like any of the

above mentioned names, but I love learning how great musicians imagine music. I

once read an interview done with a famous rock musician, Dave Grohl (of Foo

Fighters fame), and the interviewer asked him how he wrote songs. He said that

he thought of songwriting as building something out of Legos, and each colored

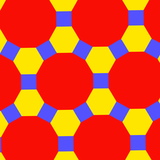

block went a certain way. I had never thought of music as being a visual

sensation, aside from reading written music on a page. I also saw a

20/20

special one night that focused on a musical prodigy who also had particular type

of savantism. Not only could he play a song perfectly after hearing it only

once, but he could also play it in different styles (jazz, blues, ragtime, etc).

I also saw a different interview many years ago about a musician who, while not

a savant, was certainly an incredible player. He said that each sound was its

own color and when he sat down to play, he pictured the colors coming from the

keyboard.

All of those experiences came

together when I decided on a topic. Early in the semester, I noticed a great

amount of music present in the texts, most notably in the slave narratives and

Song of

Solomon. Music is not something exclusive to a

certain minority culture, but it certainly played a large role in those texts.

It has the mysterious power to bring people together and unite them. In the case

of the slave narratives and

Solomon, it united the

blacks as their own culture. The dominant culture may hear the music and enjoy,

but there is always “more to the story,” so to speak. The dominant culture may

never truly understand the pain and strife that hides in the words or even the

melody of those songs.

When I started writing

The Black Page,

I had no idea where it would end up, and I still do not know. I had a seedling

idea for it, but little else. I wanted it to be about a boy who is born with an

incredible gift to play music while his father struggles to play even the

simplest of chords. I also knew that the boy would see the music he played as a

scheme of colors. From there, though, I was completely in the dark. I have taken

one “true” creative writing class when I was in junior college, and I learned

one valuable lesson: let your characters lead you where they want to lead you.

So, I did just that. After a few pages, it was easy to follow the people I

created and learn their stories and what makes them tick. I like Sammy as a

character because he loves Ray Charles and classical music at the same time.

Murray, his father, is also an interesting man because he desperately wants to

be able to play, but it’s a constant struggle for him. I thought the

relationship between the two people has paired well in what I have written so

far.

Before I began I knew that I

wanted to make the characters African American, but not to make it their

defining characteristic or to even be a fact that I would have to mention

frequently. I used Toni Morrison and Louise Erdrich as examples. In

Solomon,

I knew the characters were black, but Morrison wrote the novel in such a way

that it was not something that made me mentally classify it as a “black” novel.

It was a wonderful story, and that’s what mattered. Louise Erdrich was the same

way. A point that came up in our class discussion of

Love Medicine

was that you wouldn’t be able to tell that it was a Native American themed

novel. Even someone from the dominant culture could pick up the novel and read

it and relate to many of the struggles found in its pages. In my story, Murray

struggled and had a life altering moment because of two white people, so his

hatred and resentment towards the dominant culture was deep rooted from his

childhood. He has grown up in a predominantly white world, so there is a sense

of choicelessness apparent in his character. Sammy, though, is a bit out of the

loop when it comes to the racial problems that are happening in his town. He is

aware of them, but they have not hit close to home yet to affect him. He cares

about music.

There was one of our class

objectives that I felt fit this story, which is the notion of

assimilation/resistance. Murray is especially fond of old negro spirituals and

plays his son an old spiritual song,

I’ll Fly Away,

when he was young. Murray resents white because of what they do to his father

and his piano playing friend when he was younger, so the music is his way of

resisting the psychological damage they inadvertently inflicted on him, and as

his neighbor is assembling the resistance rally because of the increased number

of violent acts that have been occurring to African Americans in their town,

Murray also believes the music will be an assimilator of the people in his town.

In agreeing to let his son play the piano at the rally, Murray wants to garner

as many people as he can to think and feel the same way he does about whites. I

set this particular passage in 1963 because of Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous

“I Have a Dream” speech that occurred in August of that year. With such a

historic moment about to occur, I felt that having Sammy’s neighbors organize

their own rally would be a suitable method of peaceful resistance to the

dominant culture.

My favorite part has been the types of descriptions

that each character gives to music. Sammy sees music as a series of colors and

each song he plays has its own pallet. Beethoven is fire, and Chopin is grey and

dreary like a rain shower. Ray Charles can be any kind of color, because he

mixed so many genres together. Murray feels music. He scolds his son for playing

something that he said felt “cold.” I cannot take credit for that description. I

watched an interview with Billy Joel where he was asked what his favorite and

least favorite keys were. He said that he didn’t like A Major. “It’s too cold,”

he said.” The Chopin “Prelude in A Major” song that Sammy plays is my nod to

Billy. For the record, it does have a cold air to it, even though it’s generally

considered a “happy” sounding song.

Most of all I wanted the music

to play a large role because in every text we have read so far, there is some

mention of music and its importance. To a minority group, it’s a defining

characteristic. Whether it was the negro spirituals in the slave narratives and

Solomon,

the religious dances of

Black Elk Speaks

or any of the other texts, music has been a crucial thread in the fabric of

minority cultures. I enjoyed writing something that (attempted) to keep true to

the goals and objectives of our class, but was also creative and allowed me to

explore a topic that is very interesting to me. It actually grew from being an

idea to something that I feel may constitute a longer work in the future. The

two main male characters had a great amount of potential to be developed

further. Most of all, they were members of a minority culture that was

experiencing a great amount of strife, even though almost a century had passed

since the end of the Civil War. What I find fascinating is how the old

spirituals from the slave days survived and are still important to the minority

culture today. It shows the true power that music holds and how it has the power

to bring people together; not drive them apart.

-M.M

![]()

It was black. Its skin was smooth, bright

and shining, almost like a mirror. Only it didn’t show you for how you really

looked—you were tinged with color. A color that, according to the close-minded

people in town was bad. Worthless. I didn’t see things that way. I never have,

nor will I ever. My way of thinking is the exception, though – not the rule.

~ 1951 ~

He was just a child when he heard it. He was begging

his mother for some milk when a

sweet, simple song came from the next room, his

father’s voice mixing with the melody. It sent the boy’s thoughts flying,

soaring. The milk no longer mattered as he stepped into the room where the

sounds were coming from. It sounded like the voice of a spirit he had never seen

but heard in long distanced dreams of his heart.

The sound was being created by his father, sitting

at a brown box against the wall – a Baldwin upright piano. It was weathered and

had seen its share of battles: its keys were yellow with age and several stuck

due to the humidity, its tuning was several tones flat, but none of that

mattered to the boy. He stood in the doorway watching his father’s fingers press

the keys to make different noises. The farther to the left his hands played, the

lower and deeper the sounds were. As he reached more to the right, the sounds

grew higher and higher. It was the sweetest sound the boy had ever heard.

The father did not notice his son standing there

until he was finished playing the song. When he looked over, he grinned and

beckoned him to come closer. The boy walked timidly, almost afraid of the giant

music box. He wasn’t sure how so many sweet sounds could come from something

that seemed so simple.

“Do you like that song?” the father asked. They boy

nodded quickly and smiled. He asked what the brown box was.

“This is our new piano,” the father said. “I guess

you like it, huh? I bought it from a man who is moving. He let me have it for

very cheap. It needs some varnish and it has to be tuned, but those are some

pretty easy fixes.”

The boy stretched his hands out to

touch some of the keys. They were smooth and warm to the touch.

“Hold on. Here,” the father said,

lifting his son into his lap. “Sit up here with me. We’ll play a song together.”

He hit a low note while the boy played two high pitched notes.

“Lightning!” the boy cried. Then he

hit the lowest note on the keyboard. “Thunder!”

He hit the combination several

times. The low notes started sounding dark, like nighttime. The high notes were

the stars in the sky. They were bright, like the sunshine. The middle notes were

mixed colors, like his box of crayons that he used. Every note was a color. The

father smiled and lifted him down.

“Want to hear me play another song?”

he asked. The boy nodded and waited patiently.

He

went into a simple melody, humming a tune gently under it. His son watched in

awe and closed his eyes. The colors were dancing around and he picked out the

bright ones that mixed

with the dark ones. They began stacking on top of each other and were reaching

to heaven. The hairs on his neck and arms started to stand up. He opened his

eyes and started watching what color matched the spot on the keyboard his father

was pressing his fingers. Each color he thought of went to a different white or

black key. He had never experienced anything like it. Some keys were all white,

and some needed a black key to make them sound right. His father kept playing

and the boy watched. Every so often he would hit a note that would sound wrong,

but would quickly correct himself. After a few minutes, his father started

singing in his deep tenor voice:

Some bright morning when this life is

over

I’ll fly away.

To a land where joys will never end

I’ll fly away, fly away.

I’ll fly away, fly away, oh glory

I’ll fly away.

When I die, Hallelujah by and by

I’ll fly away.

He sang the entire song and when he

finished, he closed the top to the keys and looked down at his son, smiling once

again. They boy hadn’t moved since he started singing his song.

“Maybe someday you can learn to play

it too, son. It’s such a beautiful instrument.”

He walked out of the room and started talking to his

wife in the kitchen. The boy walked over to the piano and climbed onto the bench

and lifted the cover of the keys. He hit one note with his index finger. He

remembered his father had his pinky and thumb at two notes in the dark sounding

part of the keys, so he stretched his fingers as best as he could, but couldn’t

hit the two notes. They were too far apart, so he settled for one that sounded

right but was closer. They sounded dark but happy. He did the same with the

other hand and found the notes he thought he saw his father use. They were

bright sounding and were also happy. He played both together and it sounded

almost like his father’s song. It sounded bright though, and the boy was happy.

His parents walked in to see him hitting the keys, and looked at each other in

disbelief.

“Did you show him how to play that?” the mother

asked, almost breathlessly.

“He just watched me play that song,” the father

said. “I didn’t show him how to make any chords. Hell, he just hit them and was

saying ‘thunder and lightning.’”

He was just as breathless as his

wife. He stepped closer and looked at the keys his son was hitting. He hadn’t

played those notes. The song he played just used three chords, and they were all

simple. His son was hitting a combination of black and white notes. He was

baffled as to what the chord actually was. The boy stopped, thinking he was in

trouble.

“No, no! Keep playing!” the mother said.

The boy grinned at his mother as she watched him hit

the same chord as before, finding it with no hesitation. This time he attempted

to sing while she smiled and chuckled. “Look at our little Mozart!”

The father was not laughing or grinning this time.

He watched his son’s fingers hit the chord that he could not identify, his brow

furrowing deep—almost frowning at his son. The chord echoed out of the room,

through the open window and into the street. The boy’s music would reach many

ears that night. The chord sent the boy soaring and he did not want to stop

playing it because it made him feel so good. Every time he hit the notes the

colors would flash and disappear, bright and vibrant. His arms grew tired though

and so did his fingers, so he stopped. His mother clapped enthusiastically for

him. The father grunted softly and forced a slow clap and unwilling smile as he

reached over and closed the keys’ cover.

“Alright, maestro,” the father said, scooping his son into his arms. “Time for bed.” He turned off the light and walked out of the room, leaving the piano in darkness.

![]()

~

1963 ~

From the same house, sounds would flood the

street when the boy came home from school and would continue until his father

got home from work at six p.m. That left him a three hour window to play what he

really wanted before his father came home and made him either stop playing those

songs made by dead white men who never knew what struggle meant, or he would

make him play some old spiritual that meant nothing to the boy but meant

everything to his father. His mother tried not to get involved much these days,

but when it came down to choosing sides, she always went with his father and

made him play the spirituals. The time between three and six, though, she let

her son play what he wanted. It frustrated the boy that he could not play

longer, but he did not have access to any other piano. His color made sure of

that. His school did not have one and there wasn’t a music store that had one on

display. Not a store that let black kids in, anyways. He was stuck playing an

old broken down Baldwin with splotchy varnish, uneven keys and a sound that was

never quite in tune.

His fingers glided smoothly and quickly across the

keys, but never hit a green note. Green notes were bad. They sounded off when

they were by themselves. He closed his eyes and the warmth of the music put a

smile on his face. He heard clapping from his front porch that was behind him

and looking over his shoulder he saw his neighbors. Frank and Shera Tutt were

sitting on the porch chairs while their daughter, Mira and her husband Jack

leaned against the wooden railing. The boy got up and gave an impromptu bow once

he finished playing the song.

“Boy, you tickle them ivories better than ol’ Ray

Charles himself!” said Jack. “Can you play some of his stuff? Come on, Sammy! Do

‘Georgia on My Mind!’”

He remembered that song—he loved Ray Charles. The

first time he heard that record, it was so sweet sounding and heartfelt. Ray

must have experienced music he did because of his blindness. Sammy closed his

eyes to remember its melody. It was bluesy, but not depressing. He hummed it

until he found the notes. It just needed one black key—G major. It was bright,

but could be dark also. It was blue.

Sammy closed his eyes as his fingers

met the keys. The sound that met his ears was sharp, but it quickly faded and

became a mix of colors. Each note was a separate glob of color, like oil on an

artist’s pallet. As he played, they mixed and swirled and morphed into new

colors. With a tiny movement of a finger, he could change the swirl from bright

and vibrant to dark and melancholy. Music was not just auditory, but visual.

Sammy knew what colors mixed and what colors could not go together. When he

played pieces by Beethoven, the colors never clashed. They were fiery, heartfelt

and even chaotic, but they never clashed. Chopin’s music was lighter. It moved

smooth like a white cloud dotted over blue skies. Sometimes the clouds had rain

in them, but the notes still moved smoothly. There was a painting Sammy saw

once. It showed the sun setting over the water where a boat was sailing. That’s

what Sammy thought of when he played Chopin. The gentle grayish-blue water and

the smooth skies.

Raindrop Prelude. My favorite. That was

smooth, like summer rain. A swirl of grey. Smooth and dreary, but never too

dreary. Let the grey raindrops hit the ground lightly. It’s not a hurricane. A

smooth shower.

Ray Charles, though…he could mix the

colors that shouldn’t have worked. He made them work. He didn’t have to see the

keys to know his notes. That’s why Sammy loved Ray so much. He could be fiery

like Beethoven and smooth like Chopin. Sometimes all at once. The songs Ray

made…the country/western album Sammy heard at his friend’s house…no matter what

he sang there was soul and pain, but there were the colors. And they were

beautiful. It wasn’t just a beauty you could see with your eyes. You could feel

it and hear it.

He felt the music like a warm embrace on a cold winter’s

night—a blanket or a crackling fire in the hearth. Ray’s voice was so warm and

inviting. The door was open to anyone who wanted to come in. It was reassuring

and comforting even during the songs of pain and loss. Songs like

I Can’t Stop Loving

You made the hair on Sammy’s neck stand on end

while a warm feeling washed over him. All it took was one note on the piano, or

one tortured cry from Brother Ray for Sammy to get wrapped in the warm embrace

of the music.

He still remembered the first time he walked in on his

father playing the piano all those years ago. His father couldn’t have been

farther from Ray but the sounds he made had sent chills up his back for the

first time. It had been true love ever since. The only problem was that he did

not know how to explain the feeling to anyone. He recalled one moment from his

childhood when he heard Ray Charles sing

You Are My Sunshine.

When the singing started, he grabbed his friends arm and gripped tight.

“Do you see that??” Sammy asked,

breathlessly.

“No…” his friend answered, clearly

frightened.

“You don’t see the colors when you

close your eyes while this is playing?” Sammy said.

“Sammy, you’re crazy, man,” his

friend chuckled. “I don’t close my eyes when I listen to this stuff. These are

the blues. That must be the colors you’re talking about.”

It wasn’t just the blues, though. It

was so many other colors, too—dark, light, vibrant, subtle. They all mixed and

swirled. It was so beautiful.

Sammy tried to let everyone else hear what he saw he closed

his eyes, but not everyone could experience the colors the way he did. Sammy’s

father could never understand why his son closed his eyes while he played, or

why he played music that wasn’t strictly spiritual.

“All music is spiritual, dad,” Sammy

once told him. “It doesn’t all have to be something slaves used to sing.

Something Beethoven or Chopin wrote can be just as heartfelt as those.”

His father still didn’t understand. Even though he was a

musician himself, he never understood Sammy’s way of thinking. Music was black

and white, warm and cold. It was almost like his father was trying to segregate

music. Black and white did not go together. It did not matter if it sounded

right. Blacks had their music and whites had theirs. Every time he sat down to

play, though, Sammy erased those lines. He brought them together and they

sounded good.

The power was in his hands.

His neighbors started clapping once he arrived at the chords

to Ray’s song. Jack and Mira started singing:

Georgia, Georgia

The whole day through

Just an old sweet song

Keeps Georgia on my mind…

He played the song with as much love and caress as

he could muster, pausing a few times to remember the song’s next melody. It

amazed him that Ray could play such beautiful music and did not need to see

anything to create it. The sounds were his eyes. Maybe Sammy didn’t experience

it the same way Ray did, but the sounds and the colors became one when Sammy

started playing. The notes were his canvas.

His fans were clapping once he

finished and his mother peeked in and smiled. She had the radio on and it was

playing a news report. The voice buzzed in with a special bulletin. This had

been common lately. More negroes arrested, some beaten for causing a stir at a

public market. They wanted equal treatment from the whites. The cops just came

in a started arresting them and beating them without question. They never

stopped to wonder that they might have had a point in protesting. Was there any

reason to stop a peace march with violence?

The radio’s words quickly reached his neighbors on

the porch. The joy from hearing the music quickly faded when they heard what was

happening to people just like them in the city. Their faces were now chipped

with despair and hopelessness.

“It just won’t stop,” Shera said. “They just keep

cutting us down.” The rest on the porch murmured in agreement.

“You know…” Jack began. “We should do our own

organization. We just won’t be in the streets for the cops to beat us and throw

us in jail. Let’s have it in an assembly hall. Sammy, you could play piano for

it. Play some songs to really get the community together.”

“Don’t mix that poor boy up in your crazy ideas,”

Shera cut in. “He’s just a boy. His daddy wouldn’t want him involved in that

kind of thing. Plus, what would us organizing solve anyway? Ain’t no one gonna

listen to a bunch of angry black folks shouting about equal treatment.”

“Hell, his daddy’d probably organize the whole damn

thing! You know how he’s always preaching about us being oppressed and living in

these run down houses while the white folks are sitting pretty off in the rich

end of town. Sammy, you play them ol’ spirituals he loves and I guaran-damn-tee

you he’d love to have you involved. He thinks them tunes speak to the true

negro,” Jack said.

Frank spoke for the first time

since sitting on the porch. He snorted before he began. “Hmph…Jack, honey,

you’re living in a damn dream world. We’d have better luck growing wings on our

shoulders and feathers on our ass and flying away before we ever get a white man

to listen to what we got to say. Ain’t nothin’ in this world that can make us

equal with them. We’re two different species. We could cure diseases, end war

and poverty and we still wouldn’t be equal with them. They won’t let us have the

same. We cook their food, but they don’t let us eat it. We

serve

the food and clean their houses, but they won’t pay us enough to let our houses

look half as good as theirs do. We write the music, but they won’t let us sing

it. We’re never equal. They won’t let us.”

The others looked down at the wooden slats of the

old front porch. Frank’s gritty voice had hints of sadness and anger, but also

of fear and acceptance. Compared to everyone else that sat on the porch, he was

old. To Sammy, though, he was wise. If Frank believed nothing could be done,

then nothing could be done.

“We should still try…” Jack said softly. “What do we

have to lose?”

Sammy looked at the piano keys. By pressing the

right ones, he could make them produce a noise that sounded sweet, or one that

brought sadness to someone’s eyes, and even anger. He never saw the world in

terms of black and white, but his father did. His neighbors did. Sammy just

cared about the music. The only black and white he cared about were the piano

keys. He wished everyone else felt the same way.

His neighbors left not long after. Sammy waved them

goodbye and continued to play, losing track of time. He didn’t notice the old,

rusty Chevrolet pull up in his driveway or his father’s work boots crunching the

gravel. The window was open and the sound poured into the driveway. Sammy’s

father, Murray, stood for a moment and listened. He hadn’t smiled at his son’s

playing in many years. He felt his son did not deserve the ability to play

anything he wanted without even trying while Murray struggled to play even the

simplest of chords. He stepped into the room and watched his son. He wasn’t

looking at the keys. He wasn’t even looking at anything. His eyes were closed.

Sammy stopped and looked at his father who stood

expressionless in the doorway. In the back of his mind, he harbored a desire for

his father to smile again and give him an ovation. He never understood why he

was in such a bad mood when he played the piano.

“Told you I didn’t like you playing that stuff,

Sam,” Murray said, clearly annoyed. “What was that?”

“Prelude in A Major by Chopin,” Sammy answered.

“Wasn’t it beautiful? It’s so short, but it has such a…”

Murray cut him short. “Don’t play it again. A Major

sounds too cold. Play something with a little warmth to it if you’re gonna play

at all. I didn’t come home just to hear some dead white guy’s music.”

Sammy didn’t answer but just nodded and closed the

keys’ cover.

![]()

~1928~

Murray had tried for years to be a

musician. In his younger teenage days, an “accidental” walk into the forbidden

back room at his father’s well-disguised watering hole during the peak of the

Prohibition days found him staring at a beaten brown upright piano with a

massive man sweating profusely and a cigarette hanging out of his mouth pounding

the keys. The whole room was loud with the clanking of glasses and jovial

laughing and conversation. From the moment he walked it, Murray wasn’t paying

attention to anything but that piano player. He had never heard anything like

it. His fingers were each doing something different, but they never hit a wrong

note. The smile never left his face.

Murray was hypnotized the entire

night. He recognized most of the tunes. Lots of blues and jazzy numbers. Then

ragtime. Murray loved Scott Joplin and when the piano player broke into “The

Entertainer” then “The Easy Winners” his foot started tapping and a warm feeling

washed over him. The music made him overwhelmed with an unexplainable warmth and

joy.

He had never felt anything like it

before. The hair on the back of his neck stood on end and a warm feeling went

over his body, almost like climbing into a bathtub. The notes the piano player

was hitting sent the feeling over him every time he played a new passage. Before

he knew it, his foot was tapping while the music pounded on and on. The room was

hot and Murray was sweating, but he knew that the temperature had nothing to do

with the warmth enveloping him. It was the music.

When the song was over, the piano

player got up from his bench and began to speak:

“I wanna slow things down a bit.

This one’s for the ladies in the crowd tonight.”

A few scattered claps answered him

as he sat back down to begin his next tune. Murray braced himself for the warm

feeling again, but to his disappointment, it didn’t come. Instead, a chill came

to his body. It felt like ice wrapped around him and he winced, almost in pain.

He was confused. Why did he feel so good with the other songs but so cold with

this one? The piano player wasn’t doing anything different—he was still hitting

the same spots on the keyboard, only what came out was cold and painful.

The song did not last as long as the

other tunes. People slow danced to it, so Murray realized that not everyone felt

the chill that he did. It was unique to him. How could he explain it to anyone?

After he finished the tune, the piano player finally got up

from his bench and took a seat at the bar. By this time, the crowd had thinned

as it was pretty early in the morning. A few stragglers sat at some tables next

to the bar. The bartender, Murray’s father, slid a tall mug his way and he

downed it in one gulp.

“Hoo! Helluva night, Jimmy!” he panted. “Aint’ never seen so

many folks get down.”

The two chatted for a few moments

while Murray did his best to stay out of the sight of his father’s watchful eye.

He was only fifteen, and he had known what happened in the back room at night

but only recently had the choppy sounds from a piano wafted through the night to

meet Murray’s ears. Tonight was the first time he had come to investigate the

strange sounds. He was never happier about going against his father’s orders.

As Piano Man was about to order

another mug, a couple of white men, one tall and one short, came in and sat next

to him. They turned a few heads, being the only whites in the bar, but Jimmy

didn’t make a fuss. He welcomed everyone who wanted to have a good time.

“Another brew, my man!”

Piano Man said.

He caught the beer that was slid from the other end

of the bar. Again, he downed it in a gulp.

The taller one next to Piano Man

raised his hand and called out for a whiskey sour. Jimmy poured the drink with

liquor that rested in glazed pottery jugs. “Dollar and a half,” he said once he

finished pouring.

“Hold on there,” the shorter man

said. “How come he ain’t paid?” He motioned to Piano Man who promptly looked

over when he saw the man motion toward him.

“He works for me. Plays the piano,”

Jimmy said. “Not that it’s any concern of yours.”

“It is my concern,” the tall man

said, annoyed. “Figured I could come in here and get drink without getting

robbed blind.” He got up slowly from his barstool.

“Dollar and a half for the drink,

gents,” Jimmy said, as calmly as possible. “If you don’t want to pay, there’s

the door.”

Murray watched as the men gripped

the bar and leaned in closer towards his father. His eyes met his son’s. Murray

knew he was busted for being in the forbidden room, but right now it didn’t

matter.

“Ain’t no negro gonna tell me what

to do!” The tall man slammed a glass down and it shattered, sending shards

towards Piano Man. He fell off the stool and landed on the ground with a loud

thud. The crowd in the sitting area of the bar grew sickeningly quiet and

watched, before a group of black men walked over to where the skuffle was

happening. The tall man grabbed Jimmy by the collar and pulled him over the bar,

socking his face and throwing him on top of Piano Man.

Murray ran over to help, but the shorter man grabbed

and held him before he could reach his father. Seeing the group rush over to

where the fight was happening, both men pulled guns from their pockets and

flashed them toward the group of men coming to break it up. They stepped back,

frightened of what the men may do next.

“Lookey here Abe, we got another

one! A youngin’!” Murray tried to squirm out of the hold he had him in, but it

was no use.

“Haha!” Abe laughed. “Let him see who’s really in charge

around here.” He reared back and kicked Piano Man in the side, then kicked Jimmy

in the stomach. Murray felt the hot tears roll down his cheeks as he struggled

helplessly against the man’s grip, unable to help his father. The man kept

kicking and kicking. This would have continued until Piano Man and Jimmy were

dead if it hadn’t been for Murray’s mother.

She rushed in with a rifle and

pointed it at the tall man’s chest. He looked at her and stopped kicking. She

was shaking with anger, but her aim could not have been clearer.

“You two men need to leave. Let my

son go and leave my husband alone. He ain’t done nothing to either of you.

Believe you me, I ain’t never missed with this gun and I’ve shot stuff ‘lot

smaller’n both of you.” Her voice was calm. Much more calm than her grip on the

gun.

The short man released Murray, who promptly helped his father

off the ground. He was spitting blood and doubled over in pain, but he could

walk. Piano Man lay there clutching his side, his eyes watering with pain.

Eventually he grabbed the edge of the bar and pulled himself up. The two men

walked slowly away from the bar with their hands up and walked out of the door.

“Daddy, you okay?” Murray asked.

His

father looked up at him and smiled. “You know you ain’t supposed to be back

here…” was all he said. The rest of the crowd at the tables started grabbing

their coats and heading toward the door also.

Murray thought about the music Piano

Man had played and how it made him feel warm. He wished he could always feel

that good. Before those white men ruined it.

From that moment on, Murray would go to the back room as often as he could and

tried to play the piano. He did not understand how Piano Man had made it sound

so beautiful. Whenever Murray tried to play it, it sounded harsh, and angry.

Nothing sounded right. He even tried hitting the same notes he saw Piano Man

play that night, but it still did not sound right. Every once in a while he’d

find a chord. When this happened, he would smile and commit it to memory for a

while, but he’d soon forget it after a few hours of being away from the piano.

As much as he loved it, music was not being kind to him.

One night Piano Man came in and

Murray gathered up as much courage as he could and pulled a barstool next to the

piano. The robust man looked at Murray and grinned.

“You Jimmy’s boy huh?”

Murray nodded.

“I saw you next to me the night them

two white men came in and caused all that trouble. You like the piano huh?”

“Yessir,” Murray said. “I never

heard anything like it.”

“Yeah, it’s a real crowd pleaser.

You ever played one?”

Murray explained how he had been

trying to learn, but hadn’t had any luck with it.

“Well here,” Piano Man said. “I’ll

show you a few things to get you started.” He put his fingers in the middle of

the keys. “This here is middle C,” he said, hitting a white note in the center

of the keys. “That’s your home. Always keep that one in sight. You ain’t always

gonna start playing on that one or even use it, but you always wanna keep that

one in sight. Like folding the page of a book to keep your place.”

Murray hit the note several times.

“There you go! These things I’m

hitting is called keys. Remember how you learned your A-B-C’s? Well, this ain’t

too much different from that. Each white note has name, A through G, then it

goes back to A. The black keys also have letters, but they’re called flats and

sharps. But, I’ll get to that part later. Now, I’ll show you things called

chords. That’s where your fingers play a buncha different notes at the same

time. Here’s one using that middle C I showed you, but we’re gonna play an E and

a G too. Those sound real good together.”

Piano Man hit the C, E, and G notes.

Murray saw that his fingers skipped over the letters D and F. “You try,” he

said, helping Murray’s fingers find the right notes.

He hit the chord a few times. It

sounded nice and warm. Murray smiled.

“There you go! Here, lemme show you something I learned when I

wasn’t much older’n you.”

Piano Man started playing a warm

melody, that made Murray’s hair stand on end. It was slow and sweet and reminded

him of something from church, an old hymn. This was a far cry from the jangling,

rolling piano from the other night. It was the sweetest sound his ears had ever

known. Once he finished playing, he got up and let Murray sit down and try.

“See? Ain’t nothin’ to it!” Piano

Man said. “You get good with that chord, and I’ll show you a new one next time

I’m here. Keep practicing it!”

Murray did. Every day that he got a

free moment he was at the piano practicing the chord. He even started moving his

fingers over to rest on the next set of white keys. It sounded good, but it was

a sad sound. He didn’t care for it much, so he moved back to the familiar notes

Piano Man showed him. He pictured himself one day being as good as he was on

piano and playing to a room full of people, making them dance and have a good

time. Every time that thought crossed his mind, he smiled.

Good to his word, Piano Man showed

up every few days and showed Murray a new chord. He called them the major

chords, and he learned all the way to the letter A. When Piano Man played the A

major chord, Murray winced a little. The feeling was back.

“What, you don’t like that one?”

Piano Man asked.

“No, it sounds…I don’t know… like

it’s cold.”

Piano Man frowned a bit. “I don’t

think so. It sounds as warm as the others. Depends on what you play after it.

Remember Murr, music depends on others. Not just other notes, but other people.

You can play the greatest music in the world but if no one hears it, then that’s

not the way it’s supposed to be. It’s meant to be heard and felt and enjoyed.

Never forget that.”

He understood that, but he still did

not enjoy the feeling he had while Piano Man played that A chord. If he could

just avoid that one and play another one instead, that would be okay with him.

Murray practiced his chords every day (even the A chord,

but not very long) until he reached the point where he didn’t pause between

playing each one. He could find the next chord without having to search his

brain for where to put his fingers. He even practiced them out of order just so

he could mix things up. He felt like he accomplished something impossible. It

wasn’t enough, though. He wanted to

play

like Piano Man, not just hit some chords. Once he felt that he mastered the

chords, he waited for Piano Man to return to show him something else.

Days passed after the last lesson,

and Piano Man didn’t return. Murray got worried, so one day at the dinner table,

he brought his concern up to his parents.

“Dad, where’s Piano Man been? He’s

supposed to show me a new lesson.”

His father paused and looked at his mother.

She nodded slowly and both his parents turned to

look at their son.

“Murray, Piano Man…he died a few

days ago. I was waiting to try to find the right time to tell you,” his father

said quietly.

Murray dropped his fork and his face

turned pale. Dead? How could the Piano Man be dead?

“But…how?” he stammered.

“Franklin down at the grocer told

me. Said they found him on the street, face down with a bullet in his back.

Remember them two who came in the bar a few weeks ago and caused all that

trouble? Well, Piano Man was playing at another bar across town. I told that

damn fool to be careful, but he never thought anyone would do anything to him…”

“What happened to him??” Murray

said, fighting back the tears.

“Well,” he said, “those two came

into the bar where he was playing. Franklin told me they waited till he stepped

outside for some air and pushed him behind the building and beat him senseless.

He tried crawling away but the short one put a bullet between his shoulders.

They didn’t have the decency to face him forward. They had to do it when he

wasn’t looking at them. Cowards.”

Murray stopped listening and ran to

the piano in the building that stood in front of their house. After all of these

weeks, the piano would be silent. He had grown to love Piano Man and what he

taught him.

He ran his fingers lightly over the

keys but couldn’t bring himself to play. He didn’t want the pain of loss to be

connected with music. It was meant to be enjoyed. He closed the key cover and

sat on the bench and cried.

![]()

Afterward

This text has gone through several changes. Each

time I read through it, I think of a new scene to add or I attempt to strengthen

an existing scene. I often find myself wondering what some of our text’s authors

would do (especially Toni Morrison and Louise Erdrich, because they have been my

two favorite authors). They make story telling seem like such an easy task. My

hope is to become as natural with it as they are. I’m in no rush to reach that

goal because I imagine it will take years to reach that kind of professional

quality of writing.

What helped this story come together most were

revising and the reworking of some of the scenes. While in communication with

Dr. White over the course of this project, he pointed out a few instances where

I began a promising scene or passage, but did not develop it. He was very

helpful in allowing me to see the promise of such scenes as Sammy’s experiences

with the colors of music, and his father’s experience with the hot/cold feeling

of music. I did not think to develop those passages in my initial draft, but as

I kept revising them I noticed their promise also.

As the characters became more familiar to me, I was

able to think of new scenes that would work with them. For example, during a

later draft I wanted to develop Murray’s past and explain why he is so bitter

towards the dominant culture and why the spiritual songs from the days of

slavery mean so much to him. From there the scene took on a life of its own. Dr.

White suggested expanding on some sections during the 1928 passage, especially

Murray’s hot/cold experience with the music. While drafting that expansion I

noticed I made Sammy’s and Murray’s physical experience with music very similar,

which I enjoyed. This way the two characters are not so different—Sammy was just

blessed with the gift of being able to play the music with little effort and

gets the added experience of seeing the music as colors. He can also feel it

just like his father. The characters’ deep histories made those passages work

and help the entire piece grow to something much more detailed than I had

anticipated.

Originally I expected this to

be a short story of fifteen to twenty pages. As I kept working with the

material, I realized that it could easily become a novel if I continue my pace.

Sometimes I finish a story and am glad to see it finished because it has in the

works for so long and the characters and plot have grown stale to me.

The Black Page

is something different. I want to keep working on this and send it in to a

literary magazine such as

Glimmer Train to see if

others enjoy it as much as I have. For the sake of our class though, I had to

pause long enough to submit it as my final paper. I knew early on that I would

be submitting a work-in-progress and not a finished, polished piece. I have

planned for the future in the story and have started drafting the next scene,

which involves Sammy’s neighbors organizing the community rally and they talk

Sammy into playing the piano for it. He wants to learn something fiery and

difficult, so he chooses Beethoven’s

Sonata in C# Minor,

the 3rd

movement (which is incredibly difficult). When he looks at the music for the

first time it looks like someone spilled ink on it because of the amount of

notes printed on the page. It’s a black page. On the following page is an early

working draft of that new scene. I hope to keep Sammy, Murray and their

neighbors close because I can see promise with this story.

Our class helped me realize the

communicative power that music can have on a culture. No matter what race,

gender or even sexual orientation, there will always be struggle; some must

endure more than others. Music can help ease the pain as I learned from the

slave narratives. It can help someone learn their history, as with

Song of Solomon.

It can be very religious like in

Black Elk Speaks. Its power

is truly endless and I wanted to show its importance in an original story.

![]()

In Progress (12/7/12)

~1963~

Jack had been serious about the

community organization. One night while Sammy and his family were sitting down

to dinner, he started knocking at the front door. Murray got up to answer it.

“Murray! Sorry to bother you, but I

was wanting to get your OK on something.”

Murray liked Jack, so he wasn’t too

upset about him interrupting the dinner. “What is it Jack?” he said.

“Well, a few days ago when we were

listening to your boy play, we heard the radio report of another beating

happening on the other end of town.”

Murray looked angry at this, his

chest puffing up and the breathing through his nostrils getting louder with each

breath.

“Anyway,” Jack continued, “I had the

idea about us putting together a community organization. Get everyone rallied

together so maybe one day we can do something about all these beatings that are

happening. It’s no bus boycott or Rosa Parks stuff but I think it’ll be a good

thing to get everyone involved in the cause. Have you heard what Dr. King has

been doing? He spoke in Detroit not too long ago. A whole bunch of folks rallied

together to support him and bring awareness to the wrongdoing the whites been

putting on us. They say he’s gonna be speaking in D.C. in a few weeks.”

“That’s all well and good Jack,”

Murray said. “I’d love to help out any way I can. But what do you need my OK

for?”

“Well, I think your boy could play

some music for it. You know, make it an event. He could play a song for us to

get everyone in the mood.”

Murray looked over his shoulder at

Sammy. He sat at the table watching the two men discuss the event. Now he waited

to see what his father said.

“Sammy,” Murray called. “Do you want

to play for a bigger audience than our next door neighbors?”

“Yes!” Sammy yelled, happy as could

be.

“There’s your answer Jack.” Murray

said. “He’ll play for you.”

“All right! Ray Charles junior gonna

play our event! ‘Preciate it, Murray. Hope to see you there. It’ll really get

everyone together.” Jack walked off the front porch and headed back to his house

next door.

Murray came and sat back down at the

table. “What are you gonna play, son?” he asked.

Sammy hadn’t really thought of it.

It had to be something that expressed struggle and strife. Musically, it had to

fiery and angry, but soft and subdued at parts. Sammy knew just the song.

“I have an idea,” he said, smiling.

![]()

While Jack was preparing the inside details for the

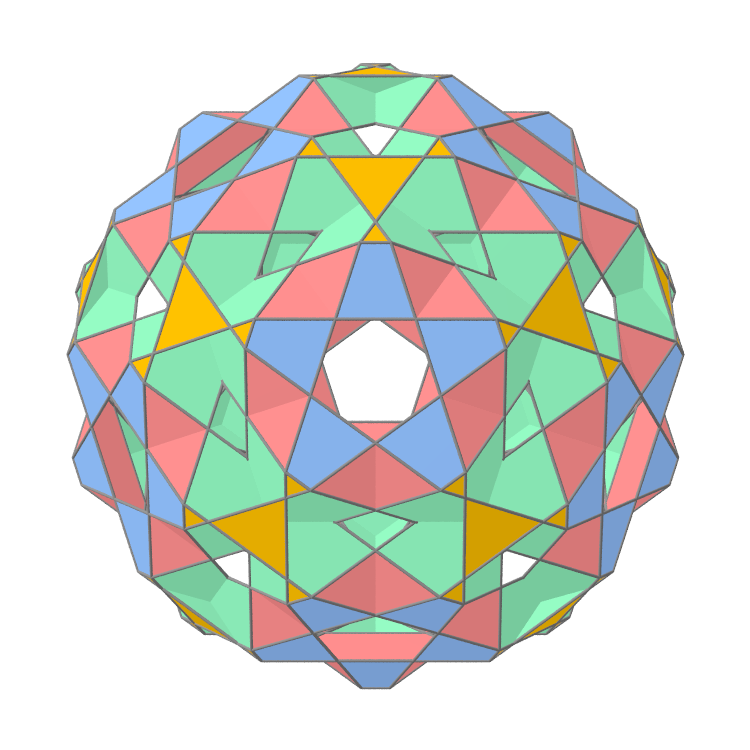

rally, Sammy was busy with other matters: his song. He heard on an old

phonograph record at his library. It was a three movement piece by Beethoven:

Sonata in C# Minor, or Moonlight Sonata as it was popularly know. The first

movement, the most famous, was smooth and to Sammy it lived up to its name. When

he heard it, it reminded him of moonlight on the ocean. It was smooth, dark and

slow. He loved it, but he did not want to play that movement.

The second movement, the Trio,

wasn’t as beautiful as the first but Sammy knew it was a stepping stone to

something greater. It held build tension and anticipation. The third movement,

Presto

Agitato, was what Sammy was interested in. When

he heard it, all he could think of was a wildfire. Flashes of red, orange and

yellow filled his head when it played over the speakers. Then, almost without

warning, it would slow down significantly and you’d hear a haunting, blue

melody. Then back to the fire. It was back and forth. Sammy loved it and he knew

it fit the negroes struggle well.

Finding the music was not an easy task, but he was

able to order it through his local music store for a dollar. He walked home with

the music tucked under his arm, practically sprinting to get back to the piano

so he could sit down and look at it. The moment finally came and he took it out

of its plastic cover and flipped through its pages. They were so covered with

notes that it was almost liked someone had spilled ink and decided to fill in

some musical notes. Sammy wasn’t frightened of it. He accepted the challenge and

was looking forward to learning it.