LITR 5535 American Romanticism

Lincoln, Stowe, Thoreau

| Conclude Douglass Stowe reading: Leigh Ann [break] Thoreau & Lincoln poetry: Aaron assignments |

|

Monday 23 October: Abraham Lincoln, N 757-760. Harriet Beecher Stowe, selections from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, N 771-806. Thoreau, N 837-853 (“Resistance to Civil Government”).

selection reader / discussion leader: Leigh Ann Moore

poetry: Theodore Roethke, "I Knew a Woman," N 2641

poetry reader / discussion leader: Elizabeth Ann Davis

specific social problem: two generations after "All men are created equal," slavery grows and spreads

larger social problem: experiment of moral society in a political state in which religion is private, neither promoted nor discouraged by the state (issue is not just political but economic: capitalism defines good in terms of property and profits, not any higher spiritual good--though the concepts are not necessarily contradictory)

How to influence the American state morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

Context for this class

Last week through next week

Peak period of American Romanticism as concurrent with "American Renaissance" or antebellum decades (i. e., before Civil War)

Period when literature and history blended--sometimes hard to know which you're talking about

Last week: American Renaissance as first great generation of African American writers, primarily writing "slave narratives"--literature inseparable from history of abolition

This week, two white literary activists in abolition movement plus American President most identified with end of slavery

Conclude Douglass

Question from last class: how to teach classic literature in a multicultural society?

1. European Romanticism > American Romanticism > African America?

2. Romanticism as escapist nonsense or historical engagement?

3. 1776: All men are created equal > 1840s-1865: greater realization

Objective 2: Cultural Issues:

America as Romanticism, and vice versa

· Americans as racially divided but historically related people develop "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature, from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age to the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs; the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen; and the American Indian as a conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa. (Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—class will discuss.)

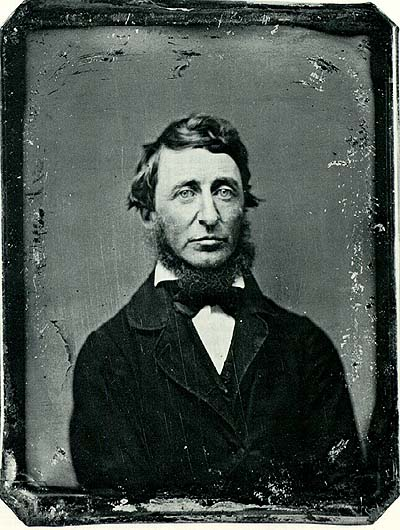

Thoreau

838 "the present Mexican war"

Texas Independence from Mexico > Republic of Texas 1836

Annexation of Texas to USA

U.S.-Mexican War or Mexican-American War 1846-48

In the U.S., the war is sometimes called the Mexican War. In Mexico, it is called la intervención norteamericana (the North American Intervention) or la guerra del 47 (the War of '47).

"Resistance to Civil Government" published 1849

historical maps of American expansion in early 1800s

Question whether new territories would be slave or free led directly to Civil War 15 years later.

Plus questions raised as to whether southwestern lands are properly Indian, Mexican, or USA--not just legal identity but who will inhabit them.

840 "cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico . . . "

Problems of including Mexico in early American literature:

1. geographical distance b/w Southwest and New England, where most American literature in English is concentrated.

2. language differences--most literature of Southwest from early 19th century appears as journalism in Spanish, or Anglo travelers' accounts

3. In New-World Catholic countries, literacy may be more concentrated in religious orders, not as widespread among common people.

Excuses! . . . It may take only a generation to change such orientations, attitudes, knowledge. By the time your age cohort is teaching a course like this, the course may look very different--as it now looks different from when I took similar courses.

Question of what literary instruction is for . . .

Knowledge of traditions?

Training in critical thinking and discussion?

Knowledge of traditions? > whose traditions?

What selection of texts? "People of color" or "great white fathers?"

Should our readings reflect the students in the classroom, or should all students be expected to read classic texts of the western tradition?

When teaching multicultural texts like Jacobs and Douglass, what methods, emphases, and lessons?

Should the difference be emphasized, or the places where they meet?

Specifically, should we read Douglass and Jacobs as . . .

examples of slave narratives, important foundation and expression of a distinct African American literary tradition?

or as examples of Romanticism?

Broad questions:

In what ways is Douglass romantic?

What about Douglass diverges from Romanticism and/or turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

Where might the two traditions meet and influence each other?

In what ways is Douglass romantic?

slave narrative as quest

hero's desire to re-invent self, claim humanity and rights

Douglass is named after a character in a Sir Walter Scott poem

Some gothic characterizations: Mr. Gore, Mr. Severe (compare Jacobs on Dr. Flint as "demon in the pit")

What about Douglass diverges from Romanticism and/or turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

Their genre is first and foremost a slave narrative, not a romance. "Romance" is only useful for describing the form of the narrative--certainly not the content.

notes from last class, student discussion: "cracked hands," whippings, blood as reality of labor, pain, suffering--not romanticized but made real

Neither Douglass nor Jacobs have nostalgia for pastoral countryside

Jacobs 820

Douglass 946

> Harlem Renaissance associated with city, not countryside (compare American Renaissance)

Where might the two traditions meet and influence each other?

some variations from light-dark value scheme

European-derived model:

white = goodness, purity; black = evil, decay

African model?

white = oppression? daytime hours as white man's time

darkness = night as people's time, family time; fertility?

Some evidence of this in slave narratives, but keep in mind especially for Harlem Renaissance at end of semester.

Specific exercise:

Read a passage in Douglass, evaluate for both

P. 957 in anthology

“Sunday was my only leisure time. . . . My sufferings on the plantation seem now life a dream rather than a stern reality.

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails . . . .

“You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! . . . You are freedom’s swift-winged angels, that fly around the world; . . . O that I could also go! . . . If I could fly! . . . I will run away. . . . I had as well be killed running as die standing. . . It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom. . . . Meanwhile I will try to bear up under the yoke. I am not the only slave in the world. . . . It may be that my misery in slavery will only increase my happiness when I get free. There is a better day coming.”

What's Romantic about this passage?

What's African American?

What's Romantic?

individual against backdrop of nature--> Emerson, Edwards, others

transcendence

escape from here and now to future day

What's African-American?

"chains" aren't necessarily metaphorical

"the dream"--not necessarily achieved, but still a promise

"If I could fly!"--theme of "Flying Africans" in various African American texts like The People Could Fly, Song of Solomon, many others

Resolutions:

Literary study usually does not choose one voice to the exclusion of another

Instead, usually tries to "add voices"--potential problems with overloading, but potentially keeps voices in dialogue.

Therefore, the short answer is to read Douglass and Jacobs as "Romanticism" and "Multiculturalism," not to mention Feminism and other interests.

Irony: it's not a short answer . . . a semester's only so long, and students read less and less

Or they're reading differently, in different media

Methods of dialogue and discourse adapt us to change

digital / electronic media will take humanity into unimaginable territories

question whether same intellectual depth is possible as in print-reading

Model of history and literature together

966 more than Patrick Henry

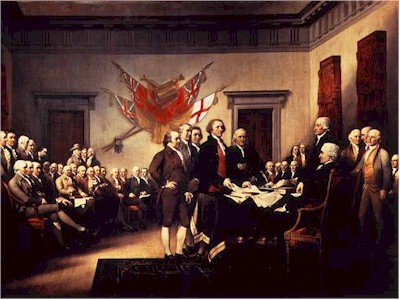

1776: American Revolution for Independence

"all men are created equal"

> 1840s-60s: Abolition of slavery + early feminism--continuity or extension of American experiment in equality, literacy, and self-government

Discuss Stowe

Uncle Tom's Cabin as "great American novel?"--diverse ways of discussing its impact and qualities

1. politically, most powerful novel in history (not just in USA--influences also in Russia, Thailand--see Anna & the King of Siam)--Lincoln to Stowe: "So you're the little woman who started this big war?"

2. revolutionized publishing industry--greatest bestseller of its time, took advantage of "second" printing revolution (steam-driven industrial presses) and of increasing literacy rates in population

p. 772, bottom paragraph

Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture

3. major contribution of first great generation of educated urban women writers, particularly of "sentimental fiction"

the "other" American Renaissance--bestsellers mostly by women, mostly concerning courtship, family, surrogate families

compare Charlotte Temple 2 generations earlier

4. Stowe as member of great American evangelical-educational family, the Beechers

Harriet, Lyman, & Henry Ward Beecher

(contrast the Beechers' "hotter" evangelical Christianity with the Transcendentalists' "cooler" Unitarianism.)

5. Stowe as one of American literature's best writers of English

Background for discussion:

As Thoreau implies in "Resistance of Civil Government," most citizens of the northern United States got along with doing business with the slaveholding south, saw it as a status quo that they couldn't easily change, someone else's business--the usual rationalizations people make concerning injustice as long as they don't perceive themselves suffering from it.

Until westward expansion, most non-Southern Americans thought slavery would eventually decline and prove unprofitable, problem would be worked out by economic and social progress

1830s-40s: expansion of slavery into new Southern states like Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Southwest territories taken from Mexico like Texas

1850: Fugitive Slave Law

1851-2: publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin, first in serial form, then as bestseller

1861-65: American Civil War

Question for discussion:

Based on your readings, how did Uncle Tom's Cabin turn Stowe into "the little woman who started this big war?"

Thoreau

|

|

|

problem of moral society in state separated from religion (not just political state, but economics of capitalism)

How to influence morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

statue of Gandhi in Herman Park

assignments

Monday 30 October: Ralph Waldo Emerson, N 482-497, 514-519, 527-533, 539-544 (introduction & opening sections of Nature, The American Scholar, Divinity School Address, & Self-Reliance). (Each student should try to finish at least one of these essays.) Margaret Fuller, N 760-771.

selection reader / discussion leader: Bill Wolfe

poetry: Denise Levertov, "The Jacob's Ladder," N 2708

poetry reader / discussion leader: Cindy L. Goodson

1. Insofar as you understand Transcendentalism, how do Emerson's writings exemplify this movement or framework of thought? Compare, contrast Thoreau, Fuller.

2. How is Transcendentalism compatible with or distinct from Romanticism?

3. How does Fuller vary Emerson's Transcendentalism in a feminist direction?

Identifying Transcendentalism

as

a movement in American Renaissance Literature

The Web of American Transcendentalism (Virginia Commonwealth University)

Project in American Literature on Transcendentalism

Like Romanticism, “Transcendentalism” is a big, baggy word that can mean many different things. Overall it's not as big or enduring a concept as Romanticism--though it can be stretched and expanded.

In the simplest historical terms, Transcendentalism is a name for a loosely associated movement or group of intellectuals, writers, and religious or social leaders in New England in the 1830s-1850s who shared similar backgrounds, styles, and interests.

Most important figures: Emerson, Fuller, Thoreau

Next in importance: Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott), Theodore Parker, Charles Ripley, Henry James Senior, Jones Very.

Sometimes other American Renaissance writers are included because of stylistic or thematic resemblances in their literature, plus some of this group were personally acquainted with the Transcendentalists.*

What these Transcendentalists had in common:

Pastors, members, or children of members of the Unitarian Church, in which Transcendentalism may be seen as a movement.

Emerson is at the center of the movement: most Transcendentalists were his friends or professional acquaintances.

History of the Unitarian Church:

17th century: Puritanism (Congregational

Church) >

late 18th century, early 19th

century: Congregationalism (Trinitarian) + Unitarian

1830s-1850s: Unitarianism > Transcendentalism

How do we get from Puritanism to Transcendentalism?

“Puritanism” is generally a bad word in modern discourse, and “hip” literary people usually shun Puritanism reflexively. But students of American literature and culture have to build a respectful relationship with the Puritans for the following reasons:

1. Puritans were highly literate people. If you’re a student of early American literature and culture, New England has far more records and texts to study than any other part of the USA. New England has continued to produce the most important writers to American literature. (Beyond the American Renaissance, think Robert Frost, e e cummings, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Thomas Pynchon.)

2. If most literary people are less than gung-ho about America’s possible image as an aggressively capitalist, imperialist nation, New England is among the only parts of the country founded for reasons other than economic opportunity a consistent home for movements involving Abolition of slavery, Women’s Rights, Pacifism, religious tolerance, and environmentalism.

How did the Puritans turn into “Yankee Liberals?”

Puritanism in New England. A “hot” church or religious movement “cools off.”

17th century: Puritanism as part of Protestant Reformation. Boston as the “City on a Hill,” the “City of God” > Salem Witch Trials

18th century: Enlightenment, Age of Reason. As education spreads, the western world opens to increasing knowledge of other religions besides Christianity and regret over excesses of religious behavior (e. g., Salem Witch Trials). “Unitarianism” appears as an attempt to recognize the “unity” of God throughout nature and the world and to “rationalize” religious behavior (e. g., to improve ethics and social justice rather than prepare for the hereafter).

Historical Note: Unitarianism is never a large, mass movement; its influence derives from social prestige and intellectual depth. At the same time that Unitarianism is emerging as a “cool” religion, “hot” religions such as Methodism, Baptistry, Mormonism, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Seventh-Day Adventists are starting to bubble up all over the country. (“Hot” religions tend to emphasize individual salvation and the wellbeing of their religious community; “cool” religions tend to emphasize social justice on a larger scale.)

Peak period of Unitarianism: late 1700s, early 1800s.

Emergence of Transcendentalism: 1830s-50s.

Is Transcendentalism a religion? Obviously some religious

themes, but never organized enough institutionally to become a religion of its

own. You could call it a religious movement, but not a religion.

Why can public schools study Transcendentalism and not Baptistry or Mormonism?

*literary prestige

*”universality” of religious themes and images—its range of reference isn’t restricted to one religion

*no conversion motive: rather than draw a person to a particular way of thinking, Transcendentalism seeks for each individual to come to terms with whatever’s at work inside.

*Why religious conservatives can still gripe:

Transcendentalism can sound like “New Age” thinking in its imagery of

self-liberation and its diverse religious traditions—though New Age writing

tends to be much lazier. Also, Unitarianism and Transcendentalism can be said to

resemble “secular humanism” in terms of de-emphasizing a supreme divine

authority beyond the human realm.

Genres: mostly non-fiction and poetry. Non-fiction may extend from Emerson’s essays to Thoreau’s intellectual memoirs to Fuller’s blend of essay and autobiography to sermons by Transcendentalist pastors.

Sometimes other American Renaissance writers are

included because of stylistic or thematic resemblances in their literature,

plus some of this group were personally acquainted with the Transcendentalists.*

*Whitman is the most frequent inclusion. His reading of

Emerson was essential to his intellectual growth (“I was simmering, simmering,

simmering . . . . Emerson brought me to a boil.”). When Whitman mailed Emerson

a first edition of Leaves of Grass,

Emerson wrote him back: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Emerson’s essay “The Poet” appears to anticipate the changes Whitman makes

in American poetry.

*Hawthorne and Melville are sometimes categorized as

“Dark Transcendentalists” (compared to Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman as

“Light Transcendentalists”). Hawthorne knew Emerson and lived in Concord

(home of Emerson and Thoreau), and some of Hawthorne’s and Melville’s

symbols and themes may resemble those of Transcendentalism. But he and Melville

were more critical than supportive of Transcendentalism, and they primarily

wrote fiction rather than the genres associated with Transcendentalism.

*Occasionally, listings will include American Renaissance writers as diverse as Emily Dickinson and Frederick Douglass among the Transcendentalists. Doubtless these authors read Emerson and other Transcendentalists, and some resemblances can be found between their patterns of thought and imagery and those of the Transcendentalists. But in such applications “Transcendentalism” becomes so broad that the term loses any historical specificity and begins to blur differences for the sake of emphasizing unity—which sounds like what the Transcendentalists were often about!

textual form of Transcendentalism

"Transcendence"--compare action at end of romance narrative

The conclusion of a romance narrative is typically “transcendence”—“getting away from it all” or “rising above it all.” The characters “live happily ever after” or “ride off into the sunset” or “fly away” from the scenes of their difficulties (in contrast with tragedy’s social engagement or comedy’s restored unity).

Thoreau 847 "a higher law"

851 a point of view a little higher

852 higher sources

852 the individual as a higher and independent power

civil disobedience backgrounds

Abraham Lincoln, N 757-760.

What's Romantic, or not, about Lincoln? (both his life and his writing)

What comparisons to Douglass?

"new birth of freedom"