LITR 5535 American Romanticism

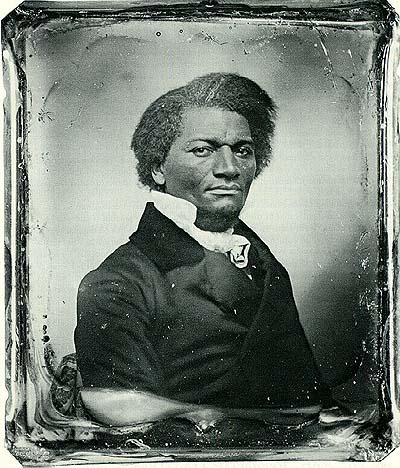

Monday 21 March: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, N 812-834. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life . . . , N 939-973.

|

|

Assignments Romanticism: escape or engagement? Douglass, Jacobs reader: Tish [break] poetry: Anuruddha More on Douglass

|

|

Monday 16 October: Research Proposal Due (within 72 hours of class). Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, N 812-834. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life . . . , N 939-973.

selection reader / discussion leader: Tish Wallace

poetry: Robert Hayden, "Those Winter Sundays," N 2669

poetry

reader / discussion leader:

Anuruddha Ellakkala

Assignments

proposals due this week

If my reply seems inadequate, don't hesitate to write again--provide more info and ask questions

Next week, continue readings in American Romantic literature of "American Renaissance" with historic interest added to usual literary analysis.

Monday 23 October: Abraham Lincoln, N 757-760. Harriet Beecher Stowe, selections from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, N 771-806. Thoreau, N 837-853 (“Resistance to Civil Government”).

selection reader / discussion leader: Leigh Ann Moore

specific social problem: two generations after "All men are created equal," slavery grows and spreads

larger social problem: experiment of moral society in a political state in which religion is private, neither promoted nor discouraged by the state (issue is not just political but economic: capitalism defines good in terms of property and profits, not any higher spiritual good--though the concepts are not necessarily contradictory)

How to influence the American state morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

Monday 30 October: Ralph Waldo Emerson, N 482-497, 514-519, 527-533, 539-544 (introduction & opening sections of Nature, The American Scholar, Divinity School Address, & Self-Reliance). (Each student should try to finish at least one of these essays.) Margaret Fuller, N 760-771.

selection reader / discussion leader: Bill Wolfe

poetry: Denise Levertov, "The Jacob's Ladder," N 2708

poetry reader / discussion leader: Cindy L. Goodson

1. European Romanticism > American Romanticism > African America?

2. Romanticism as escapist nonsense or historical engagement?

3. 1776: All men are created equal > 1840s-1865: greater realization

1. European Romanticism > American Romanticism > African America?

Classes with names like "American Romanticism" or "Medieval Literature" or "Modernism" are called "period surveys."

Earlier this semester, discussed "periodization"

(from first class on Last of the Mohicans)

Study of literary and cultural periods = "periodization"

Some students and scholars don't like study of periods > idea that literary texts should stand above or outside history, speak across history to us

Downside to this approach: student is stuck with appreciating what s/he would have already liked anyway, little chance to learn or grow

Advantages of periodization:

Building blocks of the past--avoids "flattening" of the past that we're all prone to

Another common objection to periodization:

locks all writers in same box; e. g., if this is a Romantic author, s/he must love nature . . . .

But periodization can also be used to measure difference; for instance, later in semester, Whitman writes during the Romantic period but with increasingly Realistic subject matter

Add:

Study of periods can develop knowledge of cultural evolution or progress--how does one style or concept of art lead to another? How does a style survive?

Potential downside:

Period surveys are often a parade of "great men" and "great texts"--"the authors who made history"

This kind of linear, progressive history can sometimes exclude a lot of literature written by "others"--Literature from the ground up instead of from the court down . . .

But with more students and instructors trained in multicultural literature, the problem may be in process of resolution (or evolution)

Objective 2: Cultural Issues:

America as Romanticism, and vice versa

· Americans as racially divided but historically related people develop "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature, from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age to the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs; the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen; and the American Indian as a conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa. (Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—class will discuss.)

American Indians are romanticized by dominant culture, sometimes as gothic demons or hell-hounds (compare today's terrorists), increasingly as nature-loving noble savages.

Indians' own Romantic reaction is difficult to categorize. Sometimes Indians play up to Romantic image or use Romantic principles as rhetorical devices, but depth or uniformity of commitment is iffy.

Point: American Romanticism involves non-European people(s), whose presence complicates categories or universality of "Romantic spirit."

Other major race involved in American Romanticism: African American

congruities with Romanticism:

Abolition movement corresponds to American Renaissance (1820s-1860s)

Rise of first generation of major African American writers

2. Romanticism as escapist nonsense or historical engagement?

Interpret positively and negatively:

"S/he's a Romantic" vs. "S/he's a realist"

Can a defense of Romanticism be extended to history?

American Romantic period a. k. a. "American Renaissance"

1820s-1860s

ends with U. S. Civil War, 1861-65

coincidence of American Renaissance with a number of historical movements

Manifest Destiny, expansion westward, Mexican War (mentioned by Thoreau)

Expansion of southern tier of states meant expansion of slavery, which meant that slavery wasn't dying but vital, growing

Abolition movements

Women's rights movements (Seneca Falls 1848, Margaret Fuller)

Utopian or communal movements (Shakers, Brook Farm, Fruitlands, Oneida)

(Hawthorne lived at Brook Farm for a few months, Fuller and Emerson visited; Alcott family started Fruitlands)

millennial movements: Millerites ( > 7th Day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses), Latter-Day Saints, Shakers

Evangelical movements--"Second Great

Awakening" ("Great Awakening"--i. e., the "First Great

Awakening") was approximately a century earlier, following Jonathan Edwards

(Rise of Methodism: John Wesley, George Whitefield. Rise of Baptistry.)

What is compatible between such a society and Romantic thought, art, and literature? Do they complement or contradict each other?

Last class: period of Romanticism = period of intense social dynamics, growth, change

Romanticism as anything beyond the here and now > may reflect a society for whom present reality cannot be satisfactory

Contrast realism: you're supposed to settle for what you know, value what's given

review Hawthorne

Two final questions re Hawthorne:

gothic

personal style

Ultimately inseparable.

Both contribute to answering the style question: How can you tell you're reading a Hawthorne text?

earlier scheme from Cooper's Mohicans

| gothic color scheme |

light |

dark |

red/yellow |

| Western Civilization moral metaphysics |

white as innocence, purity |

black or darkness as evil, decay |

blood? anger? |

| the races of early North America |

white people (European Americans) |

black people (African Americans) |

the "red man" (American Indians) |

Now let's change the patterns and subjects for Hawthorne

| gothic color scheme |

light |

dark |

red, yellow, etc. / shading, blending of light and dark |

| Puritan clothing, environment |

white clothes, sunshine, light of God |

dark clothes, forest, darkness of evil |

interplay of light and dark, Puritan in forest, Faith's pink ribbon |

| Western Civilization moral metaphysics |

white as innocence, purity |

black or darkness as evil, decay |

moral ambiguity |

(Look for contrast with this in African American writings, for whom these identifications are threatening.)

620 [Gothic

imagination of Puritans; correspondence]

623 prayers before

daylight, evening prayer time

Hawthorne's individual style

Hawthorne's style, highly identifiable--when you read a Hawthorne story or novel, how can you tell it's Hawthorne?

style as both literary techniques and subject matter

truth as evanescent, ephemeral, transient, elusive: "flickering," "glimmering"

"something"--

symbols

qualifiers—may have, could have

equality in sin

critical favorite because reader participates; Hawthorne's style builds in a lot of interpretation on part of reader

Bedford Glossary of Critical Terms

symbol: something that, although it is of interest

in its own right, stands for or suggests something larger and more

complex--often an idea or a range of interrelated ideas, attitudes, and

practices.

Within a given culture, some things are understood to be

symbols: the flag of the United States is an obvious example, as are the five

intertwined Olympic rings. More subtle cultural symbols might be the river as a

symbol of time . . . . [W]riters often create their own symbols by setting up a

complex but identifiable web of associations in their works.

What does it mean to "qualify" one's speech?

"So-and-so is stupid, evil, and wrong!"

(Anyone who can speak thus is extreme in their expression.)

"You need to qualify what you're saying."

back it up?

"I have seen so-and-so in many situations, and in all of them s/he has acted in such a way that no reasonable person could regard them as intelligent, moral, and just."

This is a qualified statement. Leaves wiggle room, room for disagreement, leaves room to keep talking and thinking.

Webster's definition:

1a. to reduce from a general to a particular or restricted form: modify

1b. to make less harsh or strict: moderate

1c. to alter the strength or flavor of

d. to limit or modify the meaning of

qualifiers—may

have, could have

611 though [qualifier], likeness, almost, uncertain light

616 Either . . . or [qualifier]

617 no slight similitude [indirect language, heavily qualified]

More on Douglass

Question of how to teach classic literature in a multicultural society

What selection of texts?

Should our readings reflect the students in the classroom, or should all students be expected to read classic texts of the western tradition?

When teaching multicultural texts like Jacobs and Douglass, what methods, emphases, and lessons?

Should the difference be emphasized, or the places where they meet?

Specifically, should we read Douglass and Jacobs as . . .

examples of slave narratives, important foundation and expression of a distinct African American literary tradition?

or as examples of Romanticism?

Broad questions:

In what ways is Douglass romantic?

What about Douglass turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

some variations from light-dark value scheme

European-derived model:

white = goodness, purity; black = evil, decay

African model?

white = oppression? daytime hours as white man's time

darkness = night as people's time, family time; fertility?

Some evidence of this in slave narratives, but keep in mind especially for Harlem Renaissance at end of semester.

Specific exercise:

Read a passage in Douglass, evaluate for both

P. 957 in anthology

“Sunday was my only leisure time. . . . My sufferings on the plantation seem now life a dream rather than a stern reality.

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails . . . .

“You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! . . . You are freedom’s swift-winged angels, that fly around the world; . . . O that I could also go! . . . If I could fly! . . . I will run away. . . . I had as well be killed running as die standing. . . It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom. . . . Meanwhile I will try to bear up under the yoke. I am not the only slave in the world. . . . It may be that my misery in slavery will only increase my happiness when I get free. There is a better day coming.”

What's Romantic about this passage?

What's African American?

What's Romantic?

individual against backdrop of nature--> Emerson, Edwards, others

transcendence

escape from here and now to future day

What's African-American?

"chains" aren't necessarily metaphorical

"the dream"--not necessarily achieved, but still a promise

Resolutions:

Literary study usually will not choose but will usually try to do more--this has problems, but it keeps voices in dialogue.

Therefore, the short answer is to read Douglass and Jacobs as "Romanticism" and "Multiculturalism," not to mention Feminism and other interests.

Irony: it's not a short answer . . . a semester's only so long, and students read less and less

Or they're reading differently, in different media

Methods of dialogue and discourse adapt us to change

Model of history and literature together

966 more than Patrick Henry

1776: American Revolution for Independence

> 1840s-60s: Abolition of slavery--continuity of American experiment in equality, literacy, and self-government

assignments

(From LITR 5535 2005)

web-highlight(s)

from previous semesters’ research projects: Matt Mayo

Prior to this class, I was completely

unfamiliar with the term Byronic Hero. As we discussed the term in class, I began to realize that

many of the “common” heroes of today, at least partially, fit our

definition. Our example of Magua,

from The Last of the Mohicans, presented a fairly good prototype. Other

characters such as Batman or William Wallace, from the movie Braveheart, also

spring to mind when discussing this topic. These characters present the full

range of human emotion. By

displaying their darkness and depth, we can more readily identify with them.

By way of contrast, heroes with purely good characteristics, or

one-dimensional heroes, are becoming more difficult to find.

In this genre, one of the first heroes to come to mind is Superman. Superman never shows us a dark or brooding side of his

character. For this hero, there is

a clear line between right and wrong, or good and evil.

As a result, we are given very little to work with in the way of depth

for the character. His background

is fairly well flushed out, yet Superman is very flat when compared to more

fully developed heroes, such as Jean Valjean from Les Miserables.

Subject

Headings:

What

is a Byronic Hero?

Was

Byron’s life Romantic?

Student

Paper & Internet Review

Conclusion

After completing my research, I feel I have a

better understanding of what goes into the making of a Byronic hero.

The characteristics and traits are clearly linked to the Romantic genre

of writing. Additionally, I have a greater appreciation of how Byron's

life and personality caused the development of a new literary term.

Throughout my research, I found myself trying

to identify Byronic heroes from literature or recent movies.

While going through this process, I found myself repeatedly bumping into

the standard American success storyline. Often,

a heroic character must overcome some sort of early trauma or difficulty in

order to transcend in to something greater for the betterment of others.

In this instance, the hero may have some Byronic qualities, but

ultimately falls short of being a complete Byronic hero…

Nature

in American Literature and Poetry

Introduction

Nature, particularly “an uncultivated or wild

area…or a countryside,” provides colors, expression, life, and beauty

(Oxford 968). Even the idea of

wilderness, with all of its innate beauty, inspires many people, both

artistically and philosophically. For

some, beauty and nature can cause moments of ecstasy, where they are

aesthetically lifted to another plane of consciousness.

John Miller, in his essay, “Beauty: A Path to Ecstasy,” explains:

Beauty

can lead us from the mundane to the sublime.

The beauty of Nature awakens in us the love of beauty; and if we respond

deeply, we may experience moments of ecstasy.

Beauty [and Nature] inspire the arts, whose very creative process may

occasion ecstasy. These experiences

reveal that love and bliss form the essence of our own nature.

(Abstract)

A beautiful sight in nature evokes unexplainable

emotions and feelings within a person. This

poses the question, “How can a person possibly describe these feelings brought

about by nature?” The following

journal is an attempt to understand this question through: a better

understanding of aesthetics, a survey of American authors and poets whom often

use nature in their works, and research of the differences in Nature writing

among authors of Romantic fiction, transcendentalists, and poets of the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Aesthetics?

Survey of Authors

Conclusion

Conclusion

Nature

can easily be considered a universal bond between human beings, in that any

person can, if they choose, experience it.

This journal only provides a starting point for research into theories

relating beauty and the environment and the way they are perceived by people.

Literature seems to be a reliable canvas for nature, as seen through the

works of Cooper, Emerson, Dickinson, Frost, and Cummings; however, other forms

of art might also express the aesthetic effects of beauty.

Further research may lead to the illustration of nature by Impressionist

painters, such as Monet, or to various musicians and their works.