LITR 5535 American Romanticism

Monday 14 February: James Fenimore Cooper, N 460-469. Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans, through ch. 11 (through p. 110 Penguin edition); Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), N 1432-1440 (“Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences”); handout: D. H. Lawrence on Cooper's Leatherstocking novels.

| Romanticism & modernization Review periods introduce Cooper reader: Chris Wissel Questions on Mohicans Cooper, Twain, Lawrence [break] poetry: Nguyen Le more on Mohicans assignments web: Leigh Ann Moore |

|

Monday 18 September: James Fenimore Cooper, N 460-469. Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans, through ch. 11 (through p. 110 Penguin edition); Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), N 1432-1440 (“Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences”); handout: D. H. Lawrence on Cooper's Leatherstocking novels.

selection reader / discussion leader: Chris Wissel

poetry: Cathy Song, "Heaven," N 2847

poetry reader / discussion leader: Nguyen Le

web highlight (midterms): Leigh Ann Moore

Instructor's topics / questions:

Compare / contrast Twain and Lawrence on Cooper and his worth.

Remember that Twain is a "Realist"--so his attack on Cooper is an attack on Romanticism.

Compare the "wilderness gothic" in Last of the Mohicans to Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Blair Witch Project

Romanticism & modernization

Objective

1b. The Romantic Period

· To observe Romanticism’s concentration in the late 18th through the 19th centuries and its co-emergence with the rise of the middle class, the city, industrial capitalism, consumer culture, and the nation-state.

early 1800s sometimes called "the Great Transformation"

change accelerates, affects more people

first big "kick" of current patterns of high population growth, immigration, urbanization

Romanticism as reflection / reaction to changes

Study of literary and cultural periods = "periodization"

Some students and scholars don't like study of periods > idea that literary texts should stand above or outside history, speak across history to us

Downside to this approach: student is stuck with appreciating what s/he would have already liked anyway, little chance to learn or grow

Advantages of periodization:

Building blocks of the past--avoids "flattening" of the past that we're all prone to

Another common objection to periodization:

locks all writers in same box; e. g., if this is a Romantic author, s/he must love nature . . . .

But periodization can also be used to measure difference; for instance, later in semester, Whitman writes during the Romantic period but with increasingly Realistic subject matter

periods of literature / culture we've passed through so far . . .

|

Renaissance |

The 17th Century |

Enlightenment, Age of Reason,

Neo-Classical |

Romanticism |

|

|

authors |

Columbus |

John Smith, Mary Rowlandson |

Jefferson, Ben Franklin, maybe Irving |

Irving almost Romantic; Cooper as first great American Romantic author |

|

style |

exploration accounts |

religious assertion |

scientific legalism; satire |

emotion, search for transcendent meaning |

|

values, context |

discovery of new worlds; |

Reformation & Counter- Reformation; wars of religion |

scientific revolution; establishment of modern secular state |

rise of middle class; cities; |

|

literacy issues |

printing press | Protestantism and literacy |

freedom of press |

widespread literacy and printing |

modernization accelerating

Paragraph 8 from Legend of Sleepy Hollow

I mention this peaceful spot with all possible laud; for it is in such little retired Dutch valleys, found here and there embosomed in the great State of New-York, that population, manners, and customs, remain fixed; while the great torrent of migration and improvement, which is making such incessant changes in other parts of this restless country, sweeps by them unobserved. They are like those little nooks of still water which border a rapid stream; where we may see the straw and bubble riding quietly at anchor, or slowly revolving in their mimic harbor, undisturbed by the rush of the passing current. Though many years have elapsed since I trod the drowsy shades of Sleepy Hollow, yet I question whether I should not still find the same trees and the same families vegetating in its sheltered bosom.

paragraph 14

As the enraptured Ichabod fancied all this, and as he rolled his great green eyes over the fat meadow-lands, the rich fields of wheat, of rye, of buckwheat, and Indian corn, and the orchards burthened with ruddy fruit, which surrounded the warm tenement of Van Tassel, his heart yearned after the damsel who was to inherit these domains, and his imagination expanded with the idea, how they might be readily turned into cash, and the money invested in immense tracts of wild land, and shingle palaces in the wilderness. Nay, his busy fancy already realized his hopes, and presented to him the blooming Katrina, with a whole family of children, mounted on the top of a wagon loaded with household trumpery, with pots and kettles dangling beneath; and he beheld himself bestriding a pacing mare, with a colt at her heels, setting out for Kentucky, Tennessee, or the Lord knows where.

from Rip Van Winkle

He entered the house, which, to tell the truth, Dame Van Winkle had always kept in neat order. It was empty, forlorn, and apparently abandoned. This desolateness overcame all his connubial fears—he called loudly for his wife and children—the lonely chambers rang for a moment with his voice, and then all again was silence.

He now hurried forth, and hastened to his old resort, the village inn—but it too was gone. A large rickety wooden building stood in its place, with great gaping windows, some of them broken and mended with old hats and petticoats, and over the door was painted, “the Union Hotel, by Jonathan Doolittle.” Instead of the great tree that used to shelter the quiet little Dutch inn of yore, there now was reared a tall naked pole, with something on the top that looked like a red night-cap, and from it was fluttering a flag, on which was a singular assemblage of stars and stripes—all this was strange and incomprehensible. He recognized on the sign, however, the ruby face of King George, under which he had smoked so many a peaceful pipe; but even this was singularly metamorphosed. The red coat was changed for one of blue and buff, a sword was held in the hand instead of a sceptre, the head was decorated with a cocked hat, and underneath was painted in large characters, GENERAL WASHINGTON.

He now hurried forth, and hastened to his old resort, the village inn—but it too was gone. A large rickety wooden building stood in its place, with great gaping windows, some of them broken and mended with old hats and petticoats, and over the door was painted, “the Union Hotel, by Jonathan Doolittle.” Instead of the great tree that used to shelter the quiet little Dutch inn of yore, there now was reared a tall naked pole, with something on the top that looked like a red night-cap, and from it was fluttering a flag, on which was a singular assemblage of stars and stripes—all this was strange and incomprehensible. He recognized on the sign, however, the ruby face of King George, under which he had smoked so many a peaceful pipe; but even this was singularly metamorphosed. The red coat was changed for one of blue and buff, a sword was held in the hand instead of a sceptre, the head was decorated with a cocked hat, and underneath was painted in large characters, GENERAL WASHINGTON.

There was, as usual, a crowd of folk about the door, but none that Rip recollected. The very character of the people seemed changed. There was a busy, bustling, disputatious tone about it, instead of the accustomed phlegm and drowsy tranquillity. He looked in vain for the sage Nicholas Vedder, with his broad face, double chin, and fair long pipe, uttering clouds of tobacco-smoke instead of idle speeches; or Van Bummel, the schoolmaster, doling forth the contents of an ancient newspaper. In place of these, a lean, bilious-looking fellow, with his pockets full of handbills, was haranguing vehemently about rights of citizens—elections—members of congress—liberty—Bunker’s Hill—heroes of seventy-six—and other words, which were a perfect Babylonish jargon to the bewildered Van Winkle.

. . .

Rip’s heart died away at hearing of these sad changes in his home and friends, and finding himself thus alone in the world. Every answer puzzled him too, by treating of such enormous lapses of time, and of matters which he could not understand: war—congress—Stony Point;—he had no courage to ask after any more friends, but cried out in despair, “Does nobody here know Rip Van Winkle?”

“Oh, Rip Van Winkle!” exclaimed two or three, “Oh, to be sure! that’s Rip Van Winkle yonder, leaning against the tree.”

Rip looked, and beheld a precise counterpart of himself, as he went up the mountain: apparently as lazy, and certainly as ragged. The poor fellow was now completely confounded. He doubted his own identity, and whether he was himself or another man. In the midst of his bewilderment, the man in the cocked hat demanded who he was, and what was his name?

“God knows,” exclaimed he, at his wit’s end; “I’m not myself—I’m somebody else—that’s me yonder—no—that’s somebody else got into my shoes—I was myself last night, but I fell asleep on the mountain, and they’ve changed my gun, and every thing’s changed, and I’m changed, and I can’t tell what’s my name, or who I am!” . . . .

"Rip Van Winkle" as every American generation's experience: born into one world, grow up into another

Romanticism is still a part of our cultural values because we're still living in the same epoch of hyper-change

At the very least, we can all still recognize Romantic yearnings, aspirations, narratives, images

On the other hand, more recent Romanticism tends to be more ironical, skeptical, while not quite providing substitutes

+ great tree over village inn disappears, replaced by American flag

Chronic (or desirable) condition of modern existence, exemplified by USA:

mobile society (geographically and economically)

continual state of moral and economic uncertainty as traditions disintegrate, generations separate

> nostalgia (Irving and Cooper)

> transcendence (Edwards, Emerson, Thoreau)

|

James Fenimore Cooper, 1789-1854, author of "The Leatherstocking Tales" |

|

Cooper was the first American writer to make a career as a professional novelist, and his "Leatherstocking Tales" were the first American books to become international bestsellers.

Cooper is a definitive American "Romantic" writer. His novels resemble those of the British Romantic novelist Sir Walter Scott (e. g., Ivanhoe). Cooper spent a good deal of his life in Europe, where his novels were well-received.

Cooper grew up and lived much of his life in Cooperstown, New York, named for his father who founded the city, now famous as home of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Cooper is now most famous as the author of "The Leatherstocking Tales," but he wrote a total of 32 novels during his career (1820-1851) as well as numerous books on politics and travel. Cooper is generally acknowledged as the originator of the modern sea novel (The Pilot, 1824, with many others).

"The Leatherstocking Tales" are a series of five novels that are connected by two fictional characters:

|

"The Leatherstocking" |

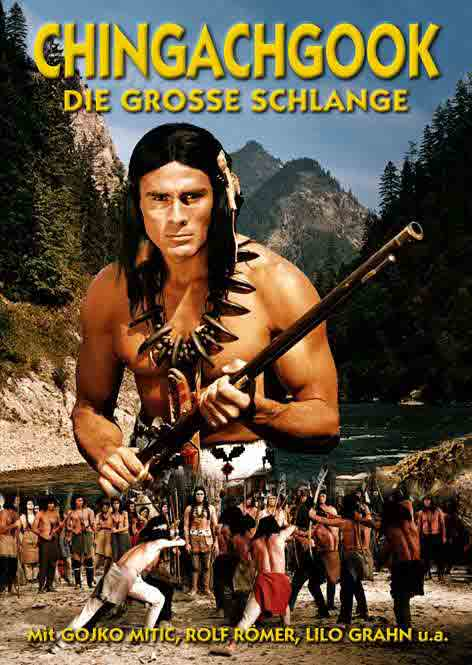

Chingachgook |

|

Significance |

Significance |

| Prototype of heroic cowboy or scout in

western novels and movies. Resourcefulness and gimmicks prefigure

Batman, etc. Lawrence: "a saint with a gun"--cf. Clint Eastwood, John Wayne, Kevin Costner --archetypal American hero combining: violence & innocence or honor (cowboys as American knights) |

Prototype of the American Indian as

"Noble Savage": silent, inscrutable, honest, deadly, poetic in

speech

Later examples: Indians in Dances with Wolves; "Go in peace, my son!" |

"The Leatherstocking Tales" in order of composition

The Pioneers (1823)

(set in the 1770-80s: Natty & Chingachgook are aging squatters near the new

fictional town of Templeton, modeled after Cooperstown)

The Last of the Mohicans

(1826)

(set during the French and Indian War of 1757-. Natty and Chingachgook are in

the prime of middle age. The title character--"the last of the Mohicans"--is

Chingachgook's son Uncas.)

The Prairie (1827)

(Setting is the western prairies of the early 1800s at the time of the Lewis and

Clark expedition. Chingachgook is dead, and Natty is a very old man who dies at

the novel's end.)

The Pathfinder (1840)

(Setting 1740s; Natty Bumppo as "pathfinder" in his 20s; military

action and courtship in years prior to Last of the Mohicans)

The Deerslayer (1841)

(Set near Cooperstown / Lake Otsego ["Glimmerglass"] in the 1730s.

Natty and Chingachgook are young men at age of first courtship and first

battles. A teenage Uncas makes a brief

appearance in an epilogue to the novel.)

Cooper, Twain, Lawrence

| author |

Cooper (1789-1851) |

Twain (1835-1910) |

Lawrence (1885-1930) |

| literary period |

Romanticism (early 19c) |

Realism (late 19th, early 20th century) |

Modernism (1st half 20c?) |

Realism: literature should represent the here and now, not the long ago and far away; dialogue should resemble normal or possible speech instead of "flowery book talk"; characters should act from real motivations (e. g., greed, lust, conscience) rather than on "codes of honor"

Modernism: mistrusts limits of Realism > interest in

symbolism, primitive powers, myth, literature as creation of truth rather than

reflection of reality

Student's Companion to James Fenimore Cooper

Instructor's topics / questions:

Compare / contrast Twain and Lawrence on Cooper and his worth.

Remember that Twain is a "Realist"--so his attack on Cooper is an attack on Romanticism.

What do you learn about Romanticism from Twain's and Lawrence's different takes on Cooper?

Compare the "wilderness gothic" in Last of the Mohicans to Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Blair Witch Project

What about Cora as a Romantic heroine?

Homepage > syllabus, schedule, etc.

assignments

Monday 25 September: “The Iroquois Creation Story,” N 17-21; “The Cherokee Memorials,” N 571-581; William Apess, N 476-482. Complete The Last of the Mohicans.

selection reader / discussion leader: Gordon Lewis (“Iroquois Creation Story”)

poetry: Joy Harjo, "Call It Fear," N 2834-5

poetry reader / discussion leader: Dee Ann Bongiovanni

What is Romantic about The Last of the Mohicans?

What is not Romantic about the American Indian texts?

Why does American popular literature and culture romanticize (or gothicize) the American Indian?

Monday 2 October: Take-home midterm exam due within 72 hours of class meeting. Edgar Allan Poe, N 694-696, 704-727 (“Ligeia” & “Fall of the House of Usher”); William Faulkner, “N 2160-66.

selection reader / discussion leader: Bonnie Napoli

poetry: Poe, "Anabelle Lee," N 2671

poetry reader / discussion leader: Corey Porter

Midterm due 2 weeks . . .

Welcome to confer

Review models on webpages--don't be afraid that you'll imitate too closely--that never happens.

Take-home Midterm Exam (due within 72 hours of 2 October)

Length: 5-7 typed double-spaced pages (equivalent).

Transmission: You must email your exam to me at whitec@uhcl.edu. Your submission will be posted to the webpage.

Topic: Develop an aspect of one of the course objectives. Describe how two or three early American texts from our assigned readings through Cooper exemplify the development of an aspect of Romanticism and how their contributions converge in The Last of the Mohicans, making it a classic or normative text of American Romanticism.

The above paragraph is the formal description of the mid-term assignment—that is, you will not be given another description of the assignment, though of course we can discuss it. The most successful versions of this exam tend to focus on a rather specific aspect of an objective, such as gothic, the sublime, nature, the Romantic hero/ine, the romance narrative, etc. You may focus more specifically than the objective indicates—that is, analyze an aspect of the gothic or a specific feature of the romance or of Romantic spirit, for instance.

You are required to review and make one citation of one of the earlier course midterms posted on the webpage. The only difference may be that summer offerings of LITR 5535 do not read The Last of the Mohicans. You are also welcome to cite external sources, though this assignment does not have a research requirement. A Works Cited is not required. You are expected to incorporate major ideas from class lecture and discussion. A member of this class should recognize your ideas and references as relevant to our course as it has developed thus far. You can’t simply express the ideas you walked in with; you must demonstrate learning.

William

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647. ch. 33:

"The Narragansetts, after the subduing of the Pequots, thought to have

ruled over all the Indians about them. But the English, especially those of

Connecticut, holding correspondency and friendship with Uncas, sachem of the

Mohegan Indians which lived near them . . . and he had been faithful to them

in the Pequot War, they were engaged to support him in his just liberties and

were contented that such of the surviving Pequots as had submitted to him should

remain with him and quietly under his protection. This did much increase his

power and augment his greatness, which the Narragansetts could not endure to

see."

Historical Uncas: flourished 1620s-30s, cooperated politically with English while resisting conversion

Fictional Uncas: 1750s (French & Indian War), great-grandson(?) of historical Uncas

(From 2005 class)

web-highlights: Marcia Toalson

Yvonne Hopkins

American Romanticism

Dr. White

Midterm

September 29, 2003

Nature’s Place in American Romanticism

Part of the lure of Romanticism lies in its ability to transcend the mundane, to challenge the limits of human consciousness, and to suspend reality in order to explore the imagination. As much as Romanticism celebrates the subjective experience of the individual, it also recognizes and values nature as a primeval force. From the early writings of the pre-Romanticists to the defining work of Cooper, nature emerges as a fundamental paradox capable of inspiring awe and terror while reflecting the elements of organic, mystical, and gothic Romanticism.

As Romanticism made the transition from the old world to the new, nature gained prominence not merely as a means “for sustained reflection or meditation,” but as an integral part of the real and the imagined experiences of humankind (Bedford 417). While European Romanticism embraces the natural environment by observing nature and exploring the dark recesses of the mind in architectural interiors, American Romanticism evolves naturally from the exterior landscapes of the forests and the formidable presence of the land.

Resoundingly, the works of the early Romanticists present a multi-faceted view of nature as more than simply a backdrop against which humankind carves its destiny. By the time Cooper develops his classic saga of frontier Romanticism, The Last of the Mohicans, the role of nature has become central to the struggles and the triumphs of the settlers in the new world. As in earlier texts, the wilderness remains fraught with “hazardous chances,” and the power of nature to debilitate reinforces the sense of its psychological grip on the outsiders: “the magnifying influence of fear began to set at nought the calculations of reason” (5, 7).

Elsewhere, Cooper expands on the antithetical notions of nature as nurturer and foe, capable of calming, restoring, and creating “a soothing impression of security” while remaining equally capable of disarming and threatening, creating “impenetrable barriers” and “barbarous sounds” (41, 59). Thus Cora and Alice take temporary comfort in the “friendly shelter of the rocks and shrubs” and “the gloom and quiet of a lovely evening” while sharing “a painful sense of their real peril” (63, 41). Moreover, the supernatural gothic elements that haunt earlier texts emerge in the enchanted forest with its “wild charms,” “healing waters,” and references to “specters,” “vaults,” demonic cries, and the devil-like appearance of the Indians (35, 72).

Although many aspects of nature’s role in Romanticism converge in The Last of the Mohicans, Cooper’s most significant contribution arises from his ability to create a vivid sense of the almost symbiotic relationship between man and his environment. In Chingachgook, Hawkeye, and Uncas, nature and man merge to create a defining oneness. In communing thus, the men of the woods assimilate into the natural environment becoming “graceful and unrestrained in the attitudes and movements of nature” (44). As such, the men possess a fundamental knowledge not only of the physicality of the land, but also an intuitive sensory ability that connects to its spirit –definitive Romanticism. In effect, the men glide in and out of the woodlands, blending into the natural landscape which provides for and protects them in life as well as in death: “Graves bring solemn feelings over the mind […] for myself, I expect to leave my own bones unburied, to bleach in the woods” [Hawkeye] (25). The significance of man’s oneness with nature is further emphasized in Uncas’s connection to the mythological turtle, the giver of life. In tracing his heritage to the turtle, Uncas establishes a noble lineage and a direct link with the natural world.

While Cooper emphasizes the noble qualities of Uncas and his companions, he also alludes to the dark side of nature in the character of Magua. Equally adept and at one with the environment, Magua’s malevolence serves as a reminder of the duality of nature and its ability to deceive and destroy. Undeniably, Cooper suggests a fundamental link between the Indians, the natural inhabitants of the land, and nature itself. Yet in the character of Cora, the potential for a similar connection develops. Of the two sisters, Alice represents the old world, removed from nature, the inhabitant of an artificial environment. In Cora, however, the mystery of her heritage, her dark looks, and her determination mark her as a woman suited to the challenges of the environment. While Alice projects the damsel in distress, Cora projects the survivor, able and willing to adapt; and, therefore, eminently worthy of taking her place in the natural setting of the frontier.

Simone Rieck

Dr. Craig White

LITR 5535

10 October 2003

Nature and the Gothic in American Romantic Literature

The roots of the term gothic can be traced back to the Medieval Period in Europe. It was most often used to describe a style of architecture “characterized by a wealth of ornamental and intricate de4tail, flying buttresses, pointed arches and vaults, narrow spires, stained glass windows, and prominent verticality” (Murfin & Ray 191). In addition to its characteristic architectural style, Europe’s history, which includes hundreds of years of war and disease, helps to create the natural setting for darkness and mystery, another gothic theme. Without the capacious history, American authors were forced to create a new gothic effect by using the lush untapped natural settings of their young country.

The groundwork of Washington Irving and Mary Rowlandson in the Pre-Romantic Era acted as a precursor for Romantic writers, such as James Fenimore Cooper, who begin to utilize the natural settings of their romance narratives to provide gothic imagery. Though Cooper’s novels are not filled with gothic descriptions, he does achieve an ambiance that effortlessly engulfs the reader. Cooper’s Deerslayer enchants readers with descriptions of the extremely young New York landscape. As Cooper tries to educate readers on the historic framework of the story, he also describes “the tangled labyrinth of a small swamp” (3) and later gives a lengthy illustration of a fallen tree:

This tree, like so many millions of its brethren, lay where it had fallen, and was moldering under the slow but certain influence of the seasons. The decay, however, had attacked its center, even while it stood erect in the pride of vegetation, hollowing out its heart, as disease sometimes destroys the vitals of animal life, even while a fair exterior is presented to the observer. (17)

Death, decay, and disease become familiar elements of the American gothic image. Not only does Cooper achieve gaining the attention of readers, he also provides an elaborate depiction of the reality of walking through the relatively unsettled frontier of early America.

Cooper’s earlier novel, The Last of the Mohicans, also uses the beautiful New York landscape to mesmerize readers. In effect, this novel also contains several depictions of the gothic in nature. When Heyward and the sisters realize they are on a Mohawk graveyard, they are overcome with unease.

Cooper illustrates:

The gray light, the gloomy little area of dark grass, surrounded by its border of brush, beyond with the pines rose, in breathing silence, apparently, into the very clouds, and the death-like stillness of the vast forest, were all in unison to deepen such a sensation. (126)

This passage contains many elements of the gothic. There is a contrast between light and dark with the description of the “gray light” and the “gloomy […] dark grass.” In addition, the “death-like stillness” involves the image of decay and illustrates the fear of the characters. Previously in the story, Cooper describes a secret entrance to a cave as “a narrow, deep, cavern in the rock, whose length appeared much extended by the perspective and the nature of the light by which it was seen” (52). The secrecy of the entrance generates mystery, and again, there is a contrast between light and dark. There is yet another gothic image later in the novel as Hawk-eye, Chingachgook, and Heyward “left the soft light of the moon, to bury themselves in the gloom of the woods” (133). Again, there is a contrast between light and dark with the descriptions of the moon and the woods. In addition, their evasion into the dark woods produces fear and anticipation, as well as mystery.