LITR 5535: American

Romanticism

Lecture notes

Monday 21 August: Introduction; students indicate presentation preferences.

|

|

|

|

|

Self-introduction

Craig White

I'll call you by your first names, so welcome to call me Craig, or Dr. White, or Professor, or Mr. White or whatever comfortable and respectable.

Some of you know me from multicultural and world literature courses, but my training and scholarship concentrated in early American literature, especially the Romantic period

My doctoral dissertation covered several of our authors

First grad course I ever taught here was this one . . . .

Have taught the course more than half a dozen times

So for better or worse, this course finds me fully loaded . . .

But American Romanticism also finds students at least partly loaded on the subject.

Nearly every American has some concept of Romanticism--it comes with the territory or with citizenship or in the air and water . . .

If I asked each of you right now, "What is Romanticism?" or "Who were some Romantic authors?", nearly all of you could come up with some kind of answer.

"What is Romanticism?" -- "love of nature" or parts of each

"Who were some Romantic authors?" -- Wordsworth, Poe, others?

Romanticism is a very big concept with a very long history, so from the start I've taught it as a survey, so that students can see it showing up at various points in various texts and movements

Not really an exotic concept--

teaching principle of starting where students are, incorporating new knowledge with established knowledge

Two verbal exercises:

What is "Romanticism?" > "Romantic" (or "romantic")

"Romantic" is a word we don't use every day, but most of us can use it or at least process it.

First Question: What do we mean when we say . . . ?

"How romantic!", or

"S/he's a romantic . . . ."

Examples? Assumptions? Words or concepts that might accompany such speech?

Second Question: What do we mean when we say . . . ?

> self-knowledge: if you're a Literature or Humanities major, you're a romantic.

Possible reaction: embarrassment . . . can't change the oil on my car or manage money . . . .like so-called "Realists" can do and think I should do . . . .

What's the value of such an identity? How and why does it survive and thrive?

Spend the whole semester and only get started, but good to get started . . . .

Romanticism is a big, essential concept in modern existence, and nearly everyone carries some of it around in their hearts and minds.

Another exercise!

Background: Romanticism as a movement is

International

(Starts in Germany in mid-to-late 1700s > France, England, other European States > North and South America)

Interdisciplinary, not just limited to literature

(Music, visual art, dance, tourism)

General progression of movements:

"Classical or Neo-Classical movement" > "Romantic movement"

(Contrast to "romantic" vs "realistic"; if you're doing history of art, it's more standard to do "Romantic" vs. "Classical")

Listen to some historical classical music

Mozart, string quartet ("Classical"; late 1700s, on verge of Romanticism)

Beethoven, string concerto ("Romantic," early 1800s, full-blown Romanticism)

Chopin, nocturne (slightly later, less heroic but still Romantic)

Warning: the period or movement distinctions made here are drastically simplified. Mozart can be pretty Romantic sometimes, and Beethoven starts out as a late Classical composer.

Questions for Mozart: How describe it as "Classical?"

Questions for Beethoven and Chopin: How describe it as "Romantic?"

Back to me: FYI

Unusual schedule this semester: two courses, both on Monday evening

After our 4-7 course, I run to an undergrad course in Creative Writing from 7-10

> Effect on office hours, etc.:

We can speak only briefly after class . . .

I have office hours Monday afternoon from 1-3

I'll be in or around my office most other afternoons Tuesday-Thursday

Phone, email, check by--I usually reply, or don't mind being reminded

types of presentations

poetry reader / discussion leader:

text-objective discussion leader (a. k. a. selection reader / discussion leader)

web highlight

web highlight postings (from LITR 5731 summer 2006)

Notes regarding postings:

Postings are required as a record of your presentation.

Most students send me their postings before class and use them as part of their presentations.

But . . . postings are not absolutely required before class, just eventually. If something goes wrong and you just "present" without a web posting, that's perfectly OK, exactly how we used to do it all the time before web projectors took over classrooms.

If you present without a posting, send the posting before the next class meeting. Please don't make me remind you.

Notes on syllabus regarding email, webpage uses . . . .

By this weekend, I'll email everyone a draft of the presentation schedule

If you see problems, reply by Sunday night; otherwise I'll bring paper copies for everyone next Monday

ID cards—volunteers for next week?

NAME as you want it to appear on schedule

contact information: email(s), phone(s), US Mail

PRESENTATION PREFERENCES

("No preference" is an acceptable answer to any of these questions.)

Would you prefer poetry, reading, or web-highlight presentation?

If poetry, particular poet or poem from listings?

If selection, particular day or author?

If web highlight, day?

(Provide me with as much information or as many options as you like)

Days when you know you won't be in class?

Volunteers for Next Monday?

Anything to tell me about your situation this semester?

assignments

Monday 28 August: Columbus, N 25-29; Selections from Genesis (handout); John Smith, N 42-53. Mary Rowlandson, N 135-152. Thomas Jefferson, N 334-342.

selection reader / discussion leader:

poetry: Anne Bradstreet, “To my Dear and Loving Husband,” N 125.

poetry reader / discussion leader:

(The Bradstreet poem is written far before the Romantic period, but how does it anticipate Romantic ideas or attitudes?)

From syllabus . . .

· For interpretation, three standard questions to consider:

1. What is “Romantic” about the poem? (Refer to course objectives or previous discussions, or speculate on additional meanings of Romanticism or “romantic.”)

2. What in the poem resists or violates Romanticism or a romantic interpretation?

3. What about the poem seems identifiably American?

Instructor's questions for readings:

Columbus:

How do Columbus's letters trace a romance narrative? How are Romanticism and America combined from the first European explorers? How does "Reality" intrude?

Columbus and Genesis:

How does Columbus recreate the Genesis story? (both in text and in popular-historical attitudes toward "discovery of America")

Mary Rowlandson:

How is this "captivity narrative" (i. e., a white settler taken hostage by the Indians) like and unlike a romance?

(Larger purpose of Rowlandson text: Cooper's Last of the Mohicans is a captivity narrative)

Jefferson pp 334-42 (intro and Declaration of Independence)

Compare to Columbus and Genesis as an "origins story" or "creation myth"

What

is Romantic about the Declaration of Independence?

(all 3 aspects of obj. 1: period, style, narrative)

Monday 11 September: Jonathan Edwards, N 182-194, 207-219; Susanna Rowson, Charlotte: A Tale of Truth (handout); Washington Irving, N 446-460 ("Rip Van Winkle"), "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (handout).

selection reader / discussion leader:

poetry: James Wright, "A Blessing," N 2752

poetry reader / discussion leader:

discuss "romance"

Objective 1: Literary Categories of Romanticism

· To identify and criticize ideas and attitudes associated with Romanticism, such as desire and loss, rebellion, nostalgia, idealism, the gothic, the sublime, the individual in nature or separate from the masses.

· The Romantic impulse may be as simple as a desire for anything besides “the here and now”—or “reality”; thus the quest or journey of the romance narrative involves crossing physical borders or transgressing social or psychological boundaries in order to attain or regain some transcendent goal or dream.

· A Romantic hero or heroine may appear empty or innocent of anything except readiness or desire to transform or self-invent.

Objective

1b. The Romantic Period

· To observe Romanticism’s concentration in the late 18th through the 19th centuries and its co-emergence with the rise of the middle class, the city, industrial capitalism, consumer culture, and the nation-state.

· To observe predictive elements in “pre-Romantic” writings from earlier periods such as “The Seventeenth Century” and the "Age of Reason."

· To speculate on residual elements in “post-Romantic” writings from later periods incl. “Realism and Local Color,” "Modernism," and “Postmodernism.”

Objective

1c: Romantic Genres

To describe & evaluate leading literary genres of Romanticism:

·

the romance narrative

or novel (journey from repression to transcendence)

·

the gothic novel

or style (haunted physical and mental spaces, the shadow of death or decay;

dark and light in physical and moral terms; film noir)

· the lyric poem (a momentary but comprehensive cognition or transcendent feeling—more prominent in European than American Romanticism?)

· the essay (esp. for Transcendentalists—descended from the Puritan sermon?)

Nearly all students become comfortable with "Romantic spirit" and "Romantic period," but less comfortable with "romance"

"romance" also in our vocabulary, but

popular usage more specialized than academic usage.

popular use: "romance" = women's novel, love story

academic use: much broader concept, can be applied to a wider range of genres

"romance" as a narrative genre

Questions:

1. What are some current or familiar examples of the romance narrative?

2. Why do students have trouble comprehending or using "romance" as an intellectual concept?

[Prof's answers to question 2:

Cognitive dissonance: students already have a concept of "romance" as "women's love story"--difficult to write over--humans avoid cognitive dissonance

Narrative itself is a difficult concept!]

guide to literary & cultural periods

| Period |

17c |

18c

Age of Reason; Enlightenment; Neoclassicism |

Late

18th-19c Romanticism |

| Dominant

intellectual power |

Religious

passion |

Reason;

empirical thought |

Imagination,

"fancy" |

| Style

and stylistic effects |

"Baroque":

extended metaphor or "conceit"; Puritan plain style |

"Classical":

clarity, symmetry, balance, temperance; satire, irony |

The

Sublime (pain & pleasure mixed on the grand scale); the Gothic (gloom,

decay, mystery); nostalgia |

| Human scene | Individual

soul, covenant or community of believers |

State

or society of autonomous equals (with many blind spots) |

Individual

alone in nature; society in older, gothic settings |

| Where's

God? (or spirit) |

Individual

soul, coventant, community |

God

created nature, but separate from nature; "Providence" |

God

or spirit increasingly dispersed in nature; also in individual human |

| Representative

European authors |

Donne,

Herbert, Milton |

Racine,

Corneille, Dryden, Pope, Swift, Johnson |

Goethe,

Schiller, Hugo, Dumas, Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley(s), Keats |

| Representative

American authors |

Taylor,

Bradstreet, Mather, Rowlandson, Edwards |

Franklin,

Jefferson, Paine |

Early:

Freneau, Irving, Cooper; "American Renaissance" (1840s-50s):

Poe, Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, Stowe,

Douglass |

| Music

(European) |

Bach,

Handel, Vivaldi |

Mozart,

Haydn |

Beethoven,

Chopin, Schubert, Wagner, Tchaikovsky |

| Role of literature | Exploration

and development of religious feeling; Expression of shared values in

community of faith |

Rational

exposition and analysis of physical and human nature. Community of shared

interests |

Entertainment

and escape for leisured classes; modeling of manners and behavior in

rapidly changing society |

| Attitude

toward social difference |

"Us

and Them"; for us or against us |

Tolerance;

diversity of human nature recognized + attempt to recognize universal

human rights |

Sympathy;

rebel or outsider becomes hero |

| Attitude

toward government |

Religious

state; early nationalism |

Limited

government, low taxes, freemarket economics |

Rise

of bourgeois nation-state (France under Napoleon); imperial expansion |

European and American names and periods

| Category / period | Eighteenth

Century

"Enlightenment," "Age of Reason," "Neo-Classical," "Classical" period |

Early

19th Century

Age of Revolution Romantic period |

| Music | "Classical Music"

Haydn Mozart |

"Romantic Music"

Beethoven, Chopin, Schubert, Liszt, Wagner |

| Art | Poussin, David, Copley, Caspar | Constable, Turner, Cole, Church |

| Literature | England: Pope, Swift, Johnson

USA: Franklin, Hamilton, Madison, Paine, Jefferson |

Germany:

Goethe, Heine, Schiller

France: Lamartine, Hugo England (1788-1832): Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Percy & Mary Shelley, Keats, Brontes USA (1820s-1861, a. k. a., "American Renaissance): Cooper, Emerson, Hawthorne, Poe, Lincoln, Fuller, Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, Thoreau, Stowe, Douglass |

| "ideology": material reality & attitudes | Established material base,

institutions, and ideology of modern civilization:

· Capitalism (Wealth of Nations, 1776) · Scientific revolution (Newton) · Urbanization, internationalization · Increasing lifespans, population growth · USA: Declaration and Constitution |

Increased leisure, affluence,

& dislocation depend on 18th-century institutions but

foster contrary aesthetics:

· Conformity / Individualism · Industrialization, urbanization, growth, devastation of nature, revolution in lifestyles / sentimental love of nature, tradition · Loss of extended family / glorification of nuclear family, domesticity, "family values" |

European-American

Art, Classical and Romantic

Classical (eighteenth century; “Enlightenment,” scientific revolution, “Age of Reason”)

stylistic tendencies: hard edges, clear colors, focused light

subject tendencies: historical figures, social and historical settings, human figures in foreground

Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego (1647)

John Singleton Copley, Death of Major Pierson, 1782-84

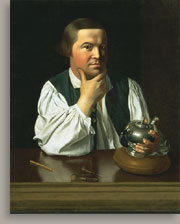

Copley, Paul Revere 1768-70

Copley, Mrs. Thomas Boylston 1766

Romantic (nineteenth century; urbanization and industrialization) “Hudson River School” of American Romantic painters

· For interpretation, three standard questions to consider:

1. What is “Romantic” about the poem? (Refer to course objectives or previous discussions, or speculate on additional meanings of Romanticism or “romantic.”)

2. What in the poem resists or violates Romanticism or a romantic interpretation?

3. What about the poem seems identifiably American?

Thomas Cole, Hunter’s Return 1845

Cole, scene from Last of the Mohicans

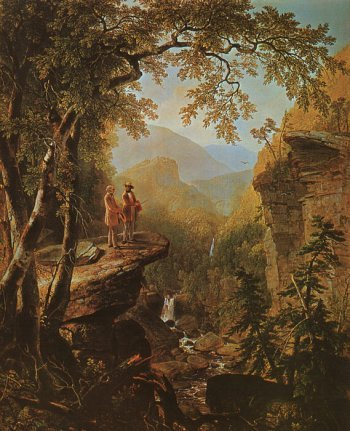

Asher Brown Durand, Kindred Spirits 1849

George Inness, Lackawanna Valley 1855

Frederic Edwin Church, Niagara Falls 1857

Church, Icebergs 1861

compare Classical and Romantic treatments of similar subjects

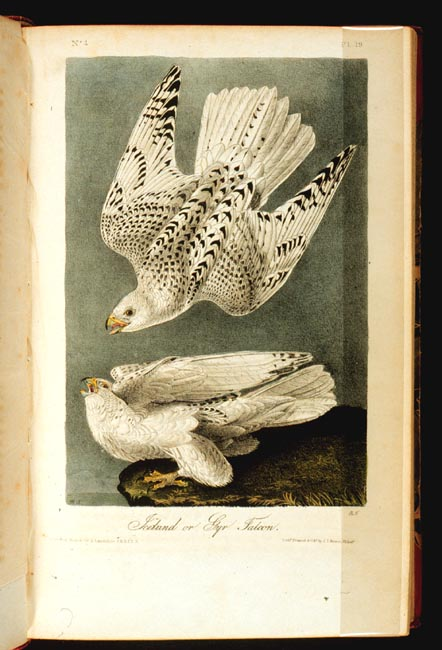

Audubon, Gyrfalcon 1833

Heade (1819-1904), Hummingbirds & Orchids (no date)

Classical (eighteenth century; “Enlightenment,” scientific revolution, “Age of Reason”)

stylistic tendencies: hard edges, clear colors, focused light

subject tendencies: historical figures, social and historical settings, human figures in foreground

Romantic painting

stylistic tendencies: softer edges and colors, diffuse light

subject tendencies: nature, human figures in background, human figures diminished, human figures not historical but fictional or “types”