LITR 5535 American Romanticism

Walt Whitman, N 985-989, 1061-1066 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1074-1080 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (handout). Carl Sandburg, N 1916-1919. Allen Ginsberg, N 2730-2740. Thomas Wolfe, “The Lost Boy” (handout).

|

|

assignments

Whitman: Kristen Bird [break] Wolfe poetry: Marion Carpenter

|

|

Monday 6 November: Walt Whitman, N 985-989, 1061-1066 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1074-1080 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (handout). Carl Sandburg, N 1916-1919. Allen Ginsberg, N 2730-2740. Thomas Wolfe, “The Lost Boy” (handout).

selection reader / discussion leader: Kristen Bird

poetry: Whitman, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” N 1070

poetry

reader / discussion leader: Marion

Carpenter

Assignments

Review syllabus-clarification from last week:

Research project due around 20 Nov., not 13 Nov.

Review course progress

Pre-Romantic > Romantic > post-Romantic

Survivals or revivals of Romantic style in later literary periods; participation in style by Native American and African American writers

Final 3 class meetings concern periods or movements after Romanticism / American Renaissance

next week: Realism (esp. "Psychological Realism"--Henry James and Edith Wharton)

following week: Local Color / Regionalism

final week: Harlem Renaissance / Modernism

Monday 13 November: Henry James, N 1498-1539 (Daisy Miller: A Study)

selection reader / discussion leader: Sharon Lockett

poetry: Elizabeth Bishop, “The Fish,” N 2650

poetry reader / discussion leader: Ashley Christine Huff

web highlight (final exams or research projects): Gordon Lewis

James (1843-1916) normally associated with "Realism," dominant American literary style after American Renaissance and Romantic era.

What traces of Romanticism remain?

What happens instead of Romanticism?

How essential is some element of Romanticism or romance for reader interest? (Daisy Miller was James's most popular story.)

p. 1223 Civil War > Industrialization, immigration

1227 Realism

Monday

20 November: Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), N

1237-1244 (“The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County”). Sarah Orne

Jewett, N 1586-1594. Charles W.

Chesnutt, N 1630-1639 (“The

Goophered Grapevine”). Wovoka, N

1789-92. Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (Zitkala Sa), N

1792-1807. Black Elk & John G. Neihardt, N

1823-1836. Research Project due (within

72 hours of class).

selection reader / discussion leader:

poetry: Simon J. Ortiz, “Earth and Rain, the Plants & Sun,” N 2814-2815

poetry reader / discussion leader: George Otis

web highlight (final exams): Kristen Bird

email to Dr. McNamara asking for his syllabus in LITR 5536 American Realism

Purpose: in two weeks in LITR 5535 (which will happen in spring again at TDCJ) we're penetrating further into the so-called Realistic era, more specifically what your people call Regionalism, but don't have a presenter on account of student changes.

I'm considering asking students who share our two courses to discuss how they've managed conceptualizing the two courses together. Might help if I actually conceptualized your course, so please send syllabus or a link to it if handy.

LITR 5536 American Realism syllabus

Monday 27 November: Claude McKay, N 2082-2086. Zora Neal Hurston, N 2096-2109. Jean Toomer, N 2120-2126. Langston Hughes N 2225-2232. Countee Cullen, N 2245-2249; F. Scott Fitzgerald, N 2126-2143 (“Winter Dreams”).

selection reader / discussion leader: Brouke M. Rose-Carpenter

poetry: Gwendolyn Brooks, "kitchenette building," N 2698

poetry reader / discussion leader: Crystal Reppert

Monday 4 December: Final exam. Students may take final exam in-class or by email.

Assignments from last week

Whitman + a group of later writers whose work is either influenced by or otherwise resembles his

Monday 6 November: Walt Whitman, N 985-989, 1061-1066 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1074-1080 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (handout). Carl Sandburg, N 1916-1919. Allen Ginsberg, N 2730-2740. Thomas Wolfe, “The Lost Boy” (handout).

selection reader / discussion leader: Kristen Bird

poetry: Whitman, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” N 1070

poetry

reader / discussion leader: Marion

Carpenter

Whitman breaks out during Romantic era, many Romantic tendencies; but also some Realistic tendencies.

Broad question: What Romantic and Realistic styles or subjects appear in Whitman, and how does he resolve these different impulses or interests?

Whitman most powerful influence on American poetry

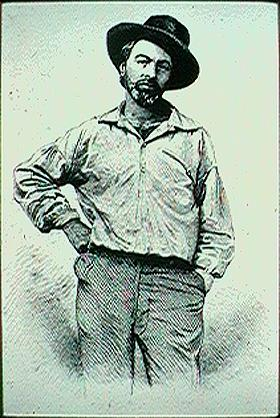

In literary studies, Whitman is generally regarded as "America's greatest poet."

"greatest" doesn't necessarily mean "best" or "finest" but impact on literature

Changes subject matter of poetry--instead of poetry just being about pretty flowers and heroes of the past and noble sentiments, poetry becomes more about everyday life, including the streets and farms of common American life, its common people, and the problems they face in terms of democracy, sexual identity, race, etc.

Changes style of poetry--instead of writing traditional poetic forms like sonnets and ballads, Whitman is the first major poet to write "free verse"--i. e., poetry without regular rhyme or fixed numbers of accents per line

Attitude of students tends to be less excited about these changes because wide-open subject matter and free verse are now standard for poetry, taken for granted

opportunity to refresh: How is Whitman's poetry still poetry, despite absence of formal mechanisms? What formal mechanisms remain? How does an "American style" of poetry result?

Sandberg and Ginsberg: peruse briefly for sake of continuity, influence of Whitman

Wolfe: how may prose style reflect Whitman's poetic style? What other Romantic features?

Whitman's style

Whitman as first major poet (American or otherwise) to consistently develop "free verse"--i. e., verse without regular or definite rhyme and meter

Now very familiar, even standard, except for "New Formalism" movement

How is Whitman's free verse still poetry, despite absence of formal mechanisms? What formal mechanisms remain? How does an "American style" of poetry result?

some standard free-verse techniques include assonance, alliteration, extended figures or metaphors, all of which Whitman may use here and there

But a few techniques are especially associated with Whitman, and may also be found in other American writers and speakers:

"the long line" (breath units?)

catalog

parallelism (+ anaphora)

Catalog or Catalogue

Catalog [from Greek katalogos list] 1. archaic a list; register, enumeration of items. 2 a. A list of names, titles, or articles arranged methodically, often in alphabetical order . . . with prices for articles of merchandise. c. specifically, an official publication of a university or college giving regulations and announcements

Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary, 7th ed.

Catalog is especially a feature of epic poetry, e. g., the ships in the Iliad, or

Catalog of the devils in Hell in Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1667

A multitude, like which the

populous North

Pour'd never from her frozen loyns . . . . Forthwith from every Squadron and

each Band

The Heads and Leaders thither hast where stood

Their great Commander; Godlike shapes and forms

Excelling human, Princely Dignities,

And Powers that erst in Heaven sat on Thrones;

Though of their Names in heav'nly Records now

Be no memorial, blotted out and raz'd

By their Rebellion, from the Books of Life. . . .

Say, Muse, their Names then known, who first, who last,

Rous'd from the slumber, on that fiery Couch. . .

First Moloch, horrid King

besmear'd with blood

Of human sacrifice, and parents tears . . .

Next Chemos, th' obscene

dread of Moabs Sons,

. . . .

With these in troop

Came Astoreth, whom the Phoenicians call'd

Astarte, Queen of Heav'n, with crescent Horns . . .

Thammuz came next behind,

. . . Next came one

Who mourn'd in earnest, when the Captive Ark

Maim'd his brute Image, head and hands lopt off . . .

Him follow'd Rimmon, whose

delightful Seat

Was fair Damascus, . . .

After these appear'd

A crew who under Names of old Renown,

Osiris, Isis, Orus and their Train

With monstrous shapes and sorceries . . .

Belial came last, then

whom a Spirit more lewd

Fell not from Heaven . . .

Parallelism

From A Handbook to Literature. Ed. C. Hugh

Holman, 3rd edn. Indianapolis: Odyssey, 1972.

A structural arrangement of parts of a sentence,

sentences, paragraphs, and larger units of composition by which one element of

equal importance with another is similarly developed and phrased. The principle

of parallelism simply dictates that coordinate ideas should have coordinate

presentation. Within a sentence, for instance, where several elements of equal

importance are to be expressed, if one element is cast in a relative clause the

others should be expressed in relative clauses. Conversely, of course, the

principle of parallelism demands that unequal elements should not be

expressed in similar constructions. Practiced writers are not likely to attempt,

for example, the comparison of positive and negative statements, of inverted and

uninverted constructions, of dependent and independent clauses. And, for an

example of simple parallelism, the sentence immediately above may serve. Parallelism

is characteristic of Oriental poetry, being notably present in the Psalms,

as in

The Heavens declare the glory of

God;

And the firmament sheweth his

handywork.

It is also characteristic of the songs and chants of

the American Indians. Parallelism seems to be the controlling principle

of the poetry of Walt Whitman. . . .

From The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and

Poetics. Ed. Alex Preminger. Princeton UP, 1975.

Parallelism [Gk. "side by side"] In poetry a

state of correspondence between one phrase, line, or verse with another.

Parallelism seems to be the basic aesthetic principle of poetic utterance. . . .

Parallelism of clauses is the central principle of biblical verse . . . . [T]he

poet who has certainly made the most use of this device in English is Walt

Whitman. . . .

Examples of stylistic

parallelism in Western and American discourse

From The Bible (King James Version), Ecclesiastes,

Ch. 3

- To every

thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

- A time to

be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that

which is planted;

- A time to

kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

- A time to

weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

- A time to

cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace,

and a time to refrain from embracing;

- A time to

get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

- A time to

rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

- A time to

love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace. . . .

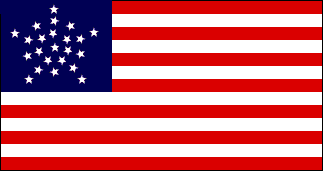

Abraham Lincoln, "Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Cemetery at Gettysburg, November 19, 1863."

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate--we can not consecrate--we can not hallow--this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little not, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget wheat they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us--that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion--that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain--that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom--and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Martin

Luther King, "I Have a Dream," 28 August 1963 [March on

Washington, D. C., delivered at the Lincoln Memorial] (from A

Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. J.

M. Washington [SF: Harper & Row, 1986], pp. 217-220]

. . . Fivescore years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

So we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the

Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory

note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was the promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white

men, would be guaranteed the unalienable

rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, American has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." . . .

So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the

difficulties of today and tomorrow, I

still have a dream. It is a dream

deeply rooted in the American dream, that one day this nation will rise up and

live out the true meaning of its creed--we hold these truths to be self-evident,

that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day, even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama . . . .

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places shall be made plain, and the crooked places shall be made straight and the glory of the Lord will be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. . . . [biblical paraphrase]

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that.

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and hamlet, from every state and city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children—black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Catholics and Protestants—will be able to join hands and to sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, free at last; thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”

*****

Broad question: What Romantic and Realistic styles or subjects appear in Whitman, and how does he resolve these different impulses or interests?

Changes subject matter of poetry--instead of poetry just being about pretty flowers and heroes of the past and noble sentiments, poetry becomes more about everyday life, including the streets and farms of common American life, its common people, and the problems they face in terms of democracy, sexual identity, race, etc.

Changes style of poetry--instead of writing traditional poetic forms like sonnets and ballads, Whitman is the first major poet to write "free verse"--i. e., poetry without regular rhyme or fixed numbers of accents per line

video from mid-1980s series, Voices and Visions about American poetry

Question: how or in what respects may Whitman's style or subject be considered either Romantic or Realistic?

Question: how does Whitman's revolution in style accommodate or complement his revolution in subject matter?

Wolfe

Questions:

In what ways is Wolfe obviously continuing to express a Romantic sensibility in the early 20th century?

How does Wolfe's prose style imitate Whitman's poetic style?

Wolfe writes at same time as Fitzgerald--Why has Fitzgerald survived while Wolfe has faded?

Wolfe 1900-1938 (Four major novels: Look Homeward, Angel [1929); Of Time and the River [1935]; The Web and the Rock [1939]; You Can't Go Home Again [1940])

Fitzgerald 1896-1940 (Four major novels: This Side of Paradise [1920]; The Beautiful and the Damned [1922]; The Great Gatsby [1925]; Tender is the Night [1934])

Both also wrote numerous short stories . . .

Possible to work in Hemingway to comparison? Especially Nick Adams stories?

Recall that Faulkner, other great fiction writer of period, appeared in class meeting on Poe.

(Short answer: Fitzgerald's a better writer, but what standards are being used to make that judgment?)

Instructor's notes:

In what ways is Wolfe obviously continuing to express a Romantic sensibility in the early 20th century?

Childhood

Loss + idealization of absence (>desire)

cycle of desire and loss (cf. Poe in "Ligeia")

industrialization as antagonist of Romantic nature or world

disappearance of lost vision into natural world / childhood

Does Romanticism blur all objects of desire together? Nature, childhood, beautiful youth (Uncas, brother, Ligeia), the past . . . .

How does Wolfe's prose style imitate Whitman's poetic style?

Use of "long line"

Attempt to capture copious and elusive reality—1689

Inclusion of common materials of everyday life

Use of long line enables (somewhat) the other two

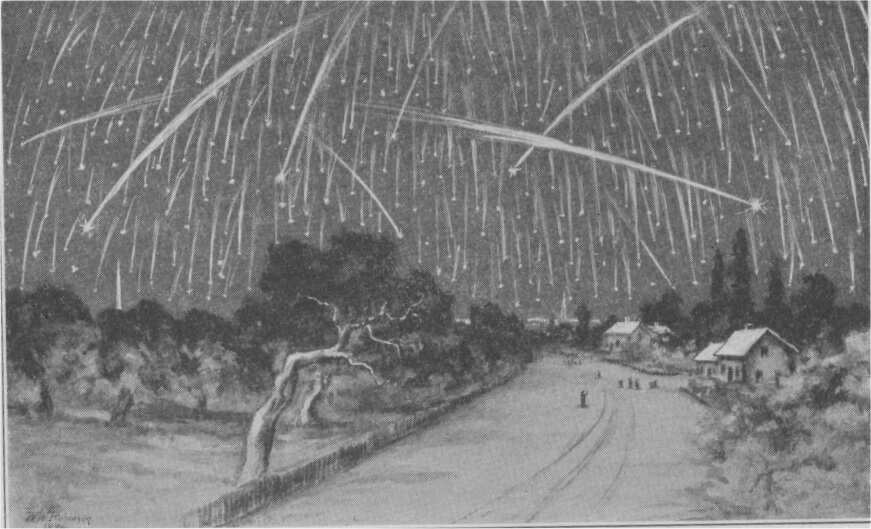

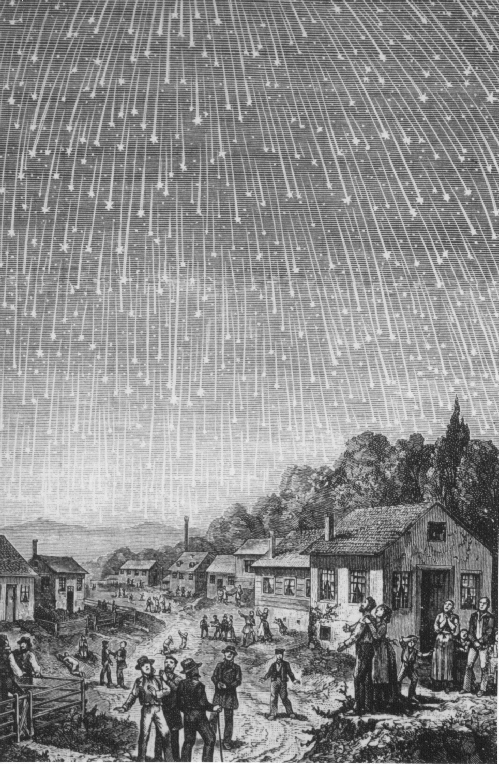

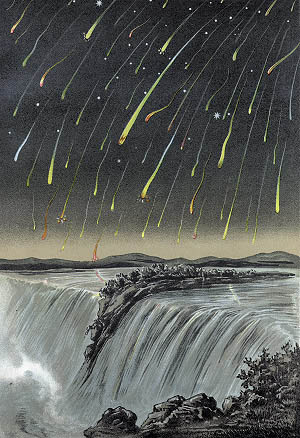

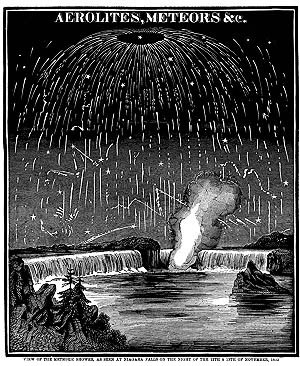

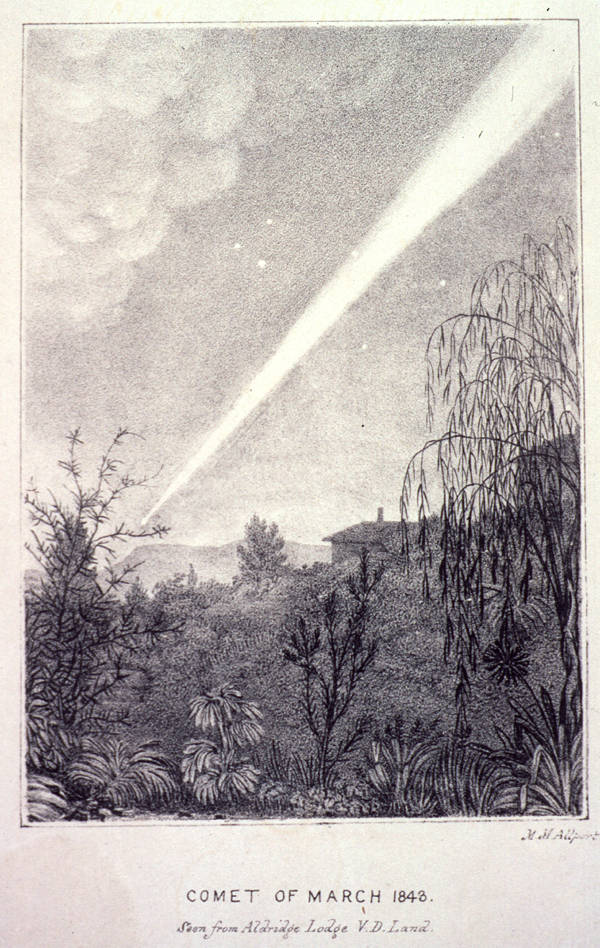

Astronomical events of American Renaissance

Meteor Storm of 1833

Great Comet of 1843

Walt Whitman, Specimen Days. Prose Works 1892, v. 1, ed. Floyd Stovall (New York UP, 1963)

94 "The Weather.--Does it Sympathize with these Times?"

Whether the rains, the heat and cold, and what underlies them all, are affected with what affects man in masses, and follows his play of passionate action, strain'd stronger than usual, and on a larger scale than usual--whether this, or no, it is certain that there is now, and has been for twenty months or more, on this American continent north, many a remarkable, many an unprecedented expression of the subtile air above us and around us. There, since this war, and the wide and deep national agitation, strange analogies, different combinations, a different sunlight, or absence of it; different products even out of the ground. After every great battle, a great storm. Even civic events the same. On Saturday last . . . . As the President came out on the capitol portico, a curious little white cloud, the only one in that part of the sky, appear'd like a hovering bird, right over him.

Indeed, the heavens, the elements, all the meteorological influences, have run riot for weeks past. Such caprices, abruptest alternation of frowns and beauty, I never knew. . . . Nor earth nor sky ever knew spectacles of superber beauty than some of the nights lately here. The western star, Venus, in the earlier hours of the evening, has never been so large, so clear; it seems as if it told something, as if it held rapport indulgent with humanity, with us Americans. Five or six nights since, it hung close by the moon, then a little past its first / 95 quarter. The star was wonderful, the moon like a young mother. The sky, dark blue, the transparent night, the planets, the moderate west wind, the elastic temperature, the miracle of that great star, and the young and swelling moon swimming in the east, suffused the soul. . . . .