Literary & Historical Utopias

|

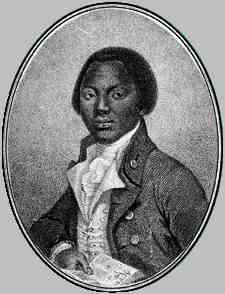

Selections from Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745-97) The Interesting Narrative of the Life (1789) |

|

From Chapter 1. The author's account of his country, and

their manners and customs--Administration of justice--. . .

. . . That part of Africa, known by the name of Guinea, to which

the trade for slaves is carried on, extends along the coast above 3400 miles,

from the Senegal to Angola, and includes a variety of kingdoms. Of these the

most considerable is the kingdom of Benen, both as to extent and wealth, the

richness and cultivation of the soil, the power of its king, and the number and

warlike disposition of the inhabitants. It is situated nearly under the line,

and extends along the coast about 170 miles, but runs back into the interior

part of Africa to a distance hitherto I believe unexplored by any traveler; and

seems only terminated at length by the empire of Abyssinia, near 1500 miles from

its beginning. This kingdom is divided into many provinces or districts: in one

of the most remote and fertile of which, called Eboe, I was born, in the year

1745, in a charming fruitful vale, named Effaka. The distance of this province

from the capital of Benin and the sea coast must be very considerable; for I had

never heard of white men or Europeans, nor of the sea: and our subjection to the

king of Benin was little more than nominal; for every transaction of the

government, as far as my slender observation extended, was conducted by the

chiefs or elders of the place. The manners and government of a people who have

little commerce with other countries are generally very simple; and the history

of what passes in one family or village may serve as a specimen of a nation.

My father was one of those elders or chiefs I have spoken of, and was styled

Embrence; a term, as I remember, importing the highest distinction, and

signifying in our language a mark of grandeur. This mark is conferred on the

person entitled to it by cutting the skin across at the top of the forehead, and

drawing it down to the eye-brows; and while it is in this situation applying a

warm hand, and rubbing it, until it shrinks up into a thick weal across the

lower part of the forehead. Most of the judges and senators were thus marked; my

father had long born it: I had seen it conferred on one of my brothers, and I

was also destined to receive it by my parents. . . .

We are all of a nation of dancers, musicians and poets. Thus every great event,

such as a triumphant return from battle, or other cause of public rejoicing is

celebrated in public dances, which are accompanied with songs and music suited

to the occasion. The assembly is separated into four divisions, which dance

either apart or in succession, and each with a character peculiar to itself. The

first division contains the married men, who in their dances frequently exhibit

feats of arms, and the representation of a battle. To these succeed the married

women, who dance in the second division. The young men occupy the third; and the

maidens the fourth. Each represents some interesting scene of real life, such as

a great achievement, domestic employment, a pathetic story or some rural sport;

and as the subject is generally founded on some recent event, it is therefore

ever new. This gives our dances a spirit and variety which I have scarcely seen

elsewhere. We have many musical instruments, particularly drums of different

kinds, a piece of music which resembles a guitar, and another much like a

stickado. These last are chiefly used by betrothed virgins, who play on them on

all grand festivals.

As our manners are simple, our luxuries are few. . . .

Our manner of living is entirely plain; for as yet the natives are unacquainted

with those refinements in cookery which debauch the taste . . . :

In our buildings we study convenience rather than ornament. . . . Houses so

constructed and furnished require but little skill to erect them. Every man is a

sufficient architect for the purpose. The whole neighbourhood afford their

unanimous assistance in building them and in return receive, and expect no other

recompense than a feast.

As we live in a country where nature is prodigal of her favours, our wants are

few and easily supplied; of course we have few manufactures. They consist for

the most part of calicoes, earthern ware, ornaments, and instruments of war and

husbandry. But these make no part of our commerce, the principal articles of

which, as I have observed, are provisions. In such a state money is of little

use; however we have some small pieces of coin, if I may call them such. They

are made something like an anchor; but I do not remember either their value or

denomination. We have also markets, at which I have been frequently with my

mother. . . .

Our land is uncommonly rich and fruitful, and produces all kinds of vegetables

in great abundance. . . . All our industry is exerted to improve those blessings

of nature. Agriculture is our chief employment; and every one, even the children

and women, are engaged in it. Thus we are all habituated to labour from our

earliest years. Every one contributes something to the common stock; and as we

are unacquainted with idleness, we have no beggars. The benefits of such a mode

of living are obvious. The West India planters prefer the slaves of Benin or

Eboe to those of any other part of Guinea, for their hardiness intelligence,

integrity, and zeal. Those benefits are felt by us in the general healthiness of

the people, and in their vigour and activity; I might have added too in their

comeliness. Deformity is indeed unknown amongst us, I mean that of shape. . . .

Our women too were in my eyes at least uncommonly graceful, alert and modest to

a degree of bashfulness nor do I remember to have ever heard of an instance of

incontinence amongst them before marriage. They are also remarkably cheerful.

Indeed cheerfulness and affability are two of the leading characteristics of our

nation.

Our tillage is exercised in a large plain or common, some hours walk from our

dwellings, and all the neighbours resort thither in a body. They use no beasts

of husbandry; and their only instruments are hoes, axes, shovels and beaks, or

pointed iron to dig with. Sometimes we are visited by locusts which come in

large clouds, so as to darken the air, and destroy our harvest. This however

happens rarely, but when it does, a famine is produced by it. I remember

an instance or two wherein this happened. This common is often the theatre of

war; and therefore when our people go out to till their land, they not only go

in a body, but generally take their arms with them for fear of a surprise; and

when they apprehend an invasion they guard the avenues to their dwellings, by

driving sticks into the ground, which are so sharp at one end as to pierce the

foot, and are generally dipt in poison. From what I can recollect of these

battles, they appear to have been irruptions of one little state or district on

the other, to obtain prisoners or booty. Perhaps they were incited to this by

those traders who brought the European goods I mentioned amongst us. . . .

As to religion, the natives believe that there is one Creator of all things, and

that he lives in the sun, and is girted round with a belt that he may never eat

or drink; but, according to some, he smokes a pipe, which is our own favourite

luxury. . . .

I have before remarked that the natives of this part of Africa are extremely

cleanly. This necessary habit of decency was with us a part of religion, and

therefore we had many purifications and washings; indeed almost as many, and

used on the same occasions, if my recollection does not fail me, as the Jews. .

. .

From Chapter 2. [The author is kidnapped from his home and sold to European slavers.]

. . . The first object which saluted my eyes when I

arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at

anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was

soon converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately

handled and tossed up to see if I were found by some of the crew; and I was now

persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were

going to kill me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long

hair, and the language they spoke (which was very different from any I had ever

heard), united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed such were the horrors of my

views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own I

would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that

of the meanest slave in my own country. When I looked round the ship too and saw

a large furnace or copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every

description chained together, everyone of their countenances expressing

dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with

horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered

a little I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those

who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in

order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by

those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair. They told me I

was not; and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in

a wine glass; but, being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One

of the blacks therefore took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little

down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, threw

me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced having

never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this the blacks who brought me

on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or

even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore which I now considered as

friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in preference to my present

situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind, still heightened by my

ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long suffered to indulge my grief;

I was soon put down hinder the decks, and there I received such a salutation in

my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the

loathsomeness of the stench and crying together, I became so sick and low that I

was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished

for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the

white men offered me eatables; and on my refusing to eat, one of them held me

fast by the hands, and laid me across I think the windlass and tied my feet,

while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced anything of this

kind before; and although, not being used to the water, I naturally feared that

element the first time I saw it, yet nevertheless, could I have got over the

nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not; and, besides, the

crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down to the decks, lest

we should leap into the water: and I have seen some of these poor African

prisoners most severely cut for attempting to do so, and hourly whipped for not

eating. This indeed was often the case with myself. In a little time after,

amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which in a small

degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of these what was to be done with us;

they gave me to understand we were to be carried to these white people's country

to work for them.

I then was a little revived, and thought, if it were no worse than working, my

situation was not so desperate: but still I feared I should be put to death, the

white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had

never seen among any people such instances of brutal cruelty; and this not only

shewn towards us blacks, but also to some of the whites themselves. One white

man in particular I saw, when we were permitted to be on deck, flogged so

unmercifully with a large rope near the foremast that he died in consequence of

it; and they tossed him over the side as they would have done a brute. This made

me fear these people the more; and I expected nothing less than to be treated in

the same manner. I could not help expressing my fears and apprehensions to some

of my countrymen: I asked them if these people had no country, but lived in this

hollow place (the ship): they told me they did not, but came from a distant one.

'Then,' said I, 'how comes it in all our country we never heard of them?' They

told me because they lived so very far off. I then asked where were their women?

had they any like themselves? I was told they had: 'and why,' said I, 'do we not

see them?' They answered, because they were left behind. I asked how the vessel

could go? They told me they could not tell; but that there were cloths put upon

the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and then the vessel went on; and the

white men had some spell or magic they put in the water when they liked in order

to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed at this account, and really thought

they were spirits. I therefore wished much to be from amongst them, for I

expected they would sacrifice me: but my wishes were vain; for we were so

quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make our escape.

While we stayed on the coast I was mostly on deck; and one day, to my great

astonishment, I saw one of these vessels coming in with the sails up. As soon as

the whites saw it, they gave a great shout, at which we were amazed; and the

more so as the vessel appeared larger by approaching nearer. At last she came to

an anchor in my sight, and when the anchor was let go I and my countrymen who

saw it were lost in astonishment to observe the vessel stop; and were now

convinced it was done by magic. Soon after this the other ship got her boats

out, and they came on board of us, and the people of both ships seemed very glad

to see each other. Several of the strangers also shook hands with US black

people, and made motions with their bands, signifying I suppose we were to go to

their country; but we did not understand them. At last, when the ship we were in

had got in all her cargo, they made ready with many fearful noises, and we were

all put under deck, so that we could not see how they managed the vessel. But

this disappointment was the least of my sorrow. The stench of the hold while we

were on the coast was so in tolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain

there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for

the fresh air; but now that the whole ship's cargo were confined together, it

became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the

climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had

scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious

perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety

of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many

died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of

their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of

the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into

which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the

women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost

inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was soon reduced so low here that it

was thought necessary to keep me almost always on deck; and from my extreme

youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I expected every hour to share

the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost daily brought upon deck at

the point of death, which I began to hope would soon put an end to my miseries.

Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep much more happy than

myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as often wished I could

change my condition for theirs.

Every circumstance I met with served only to render my state more painful, and

heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty of the whites. One day

they had taken a number of fishes and when they had killed and satisfied

themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our astonishment who were on the

deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat as we expected, they tossed the

remaining fish into the sea again, although we begged and prayed for some as

well as we could, but in vain; and some of my countrymen, being pressed by

hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no one saw them, of trying to get

a little privately; but they were discovered, and the attempt procured them some

very severe floggings. One day, when we had a smooth sea and moderate wind, two

of my wearied countrymen who were chained together (I was near them at the

time), preferring death to such a life of misery, somehow made through the

nettings and jumped into the sea: immediately another quite dejected fellow,

who, on account of his illness, was suffered to be out of irons, also followed

their example; and I believe many more would very soon have done the same if

they had not been prevented by the ship's crew, who were instantly alarmed.

Those of us that were the most active were in a moment put down under the deck,

and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the people of the ship as I

never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat out to go after the slaves.

However two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the other, and afterwards

flogged him unmercifully for thus attempting to prefer death to slavery. In this

manner we continued to undergo more hardships than I can now relate, hardships

which are inseparable from this accursed trade. Many a time we were near

suffocation from the want of fresh air, which we were often without for whole

days together. This, and the stench of the necessary tubs, carried off many. . .

.

copied with gratitude from Hanover Historical Texts Project

http://history.hanover.edu/texts/equiano/equiano_contents.html (24 May 2007)