|

|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias

|

|

Jenna Zucha

The Garden of Utopia

A recurring element and symbol in the utopian literature covered during this seminar is that of the garden. It appears as a meeting place and a means of communal competition in Thomas More’s Utopia, the garden serves as architectural motivation and inspiration in the urban utopia of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward:2000- 1887, and the garden is the physical “place” (utopia) Adam and Eve are cast out of in Genesis. Charlotte Perkins Gillman portrays the garden in Herland as a well cultivated forest that meets the needs of the entire community, “The most conspicuous feature of the whole land was the perfection of its food supply. We had begun to notice from that very first walk in the forest, the first partial view from our 'plane. Now we were taken to see this mighty garden, and shown its methods of culture” (77). The gardening aspect, in utopian literature, goes beyond the limits of a hobby; the cultivation of the garden sustains life and serves as a representation of the organization and goals of the inhabitants.

The importance or the role of the garden in utopian discussion really stood out to me and came to the forefront of my curiosity when I began researching commentary on Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood, which serves as a dystopic companion to Oryx and Crank (2003). The importance of the garden in this novel is apparent from the very beginning. The Year of the Flood opens with a hymn from The God’s Gardener’s Oral Hymnbook, which spells out how the “greedy Spoilers” came and killed God’s creatures and how all vegetation has been buried by sand. This immediate concentration on the idea of “God’s Gardeners” lead me to explore what thematic role the garden plays in Atwood’s novel ,and how it might serve utopian literature as a whole?

The Year of the Flood follows two main characters, Toby and Ren, in their attempts to survive in a post-apocalyptic world after the “waterless flood.” The flood is not sent down by God as a punishment to Man, but instead is brought on by their own disregard for the delicateness of nature and the dangers of bio-engineering. Michiko Kakutani describes in her review, “A Familiar Cast of Fighters in a Final Battle for the Soul of the Earth,” in the New York Times that the flood is “a waterless one: an uncommon pandemic that cannot be contained by “biotools and bleach,” and that sweeps “through the air as if on wings,” burning “through cities like fire, spreading germ-ridden mobs, terror and butchery.” This flood has killed millions upon millions, and electrical, digital and industrial systems are failing, as their human keepers die” (1). After her parent’s death, Toby, is rescued by the God’s Gardeners, “a hippielike sect pledged to preserve all animal and plant life” (Kakutani 1). This communal group is made up of Adams and Eves who have created roof-top gardens in the urban area outside of the Health Wyzer compound. The Gardeners must combat danger from every direction. The CorpSeCorp (a militaristic, corporation-controlled law force) is constantly tracking the Gardeners in order to shut down and destroy their roof-top utopias, while the uncontrollable pleebrats create chaos and violence within the community. Marcel Theroux explains in his review of the novel in Publishers Weekly that the Gardeners, “led by the charismatic Adam One, whose sermons and eco-hymns punctuate the narrative, the God's Gardeners are preparing for life after the prophesied Waterless Flood. As absurd as some of their beliefs appear, Atwood seems to be suggesting that they're a better option than the naked materialism of the corporations” (1). For Toby and Ren the God’s Gardeners and the gardens themselves serve as a safe haven from the dystopic and failing world that is quickly collapsing around them.

The roof-top gardens in Atwood’s novel represent a sanctuary; a fleeting attempt to regain control over nature in a post apocalyptic world. A world that has been destroyed by over population and over consumption by the ways of Man. The God’s Gardeners are using what little power they have left to restore order, through nature, to a chaotic environment. This idea is reflected in Ernest Callenbach’s novel Ecotopia in which the inhabitants of the utopia attempt to control their environment by creating interdependence with nature; a type of communal relationship. In Ecotopia the residents allow waterways to reclaim natural routes, and many trees and other plants grow harmoniously in city centers and public places. The journalist, from the United States, who is allowed to explore Ecotopia, describes the cities as having, “…sometimes planted gardens. Trees are everywhere—there are no large paved areas exposed to the sun” (Callenbach 27). The people of this utopia essentially regain control over nature by working with the ways of wilderness; they allow the land and forestry to re-establish a place within the community without destroying its disposition.

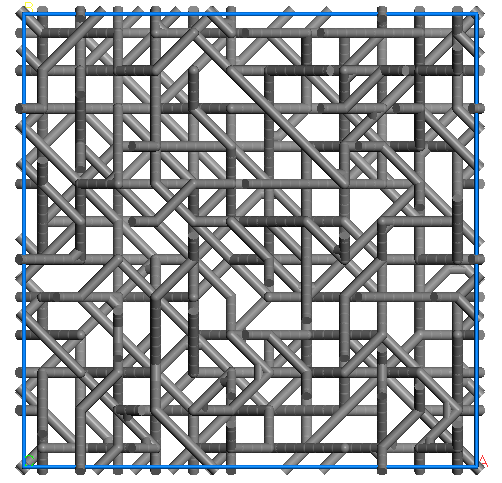

So why is the garden so influential to utopian literature? In part, it serves as an allegory for the actual process for creating and maintaining a utopic state. The garden, like utopias, attempts to bring organization and boundaries to an untamed wilderness. Gibson Burrell and Karen Dale continue this idea in “Utopiary: Utopias, Gardens, and Organization,” by explaining that “Indeed, the wilderness seems the antithesis of the garden: untamed, uncontrolled, unbounded, unpredictable, even fundamentally unmanageable and disorganized” (121). It seems impossible to control something that by definition is uncontrollable. The concept of the garden goes against nature, but it is a way of interacting with the uncontrolled in a way that benefits all. The utopian ideal functions in the same way. It recognizes the limitations of Man as an individual and attempts to place boundaries in such a way that cultivates the good and weeds out the bad for the benefit of the community. This is a constant struggle because the weeds always seem to grow back. Both the garden and the utopia must be under constant surveillance in order for them to survive, “the wilderness is often recognized as constantly within the garden. The search for complete order is usually seen as totally inappropriate by those tending the garden” (125). Utopian ideas and communities, like gardens, are not perfectly organized and must tolerate some intrusion from the outside wilderness in order to survive. This thought lead to further inquiry into the use of gardens in utopian communities outside the realm of literature.

The garden as a representation of utopic thought has expanded beyond the limitations of fiction and has impacted the construction and organization of utopian communities in reality. Burrell and Dale illustrate this through their depiction of Garden Cities, “a concept that arose in the UK, and had been expressed as early as 1827” (115). Ebenezer Howard, a prime advocate of utopian living, articulated the concept diagrammatically in 1898. His vision of the future appeared first as A Peaceful Path to Social Reform (1898), but was renamed for the second Edition Garden Cities of To-Morrow (1902). Both designs were greatly influenced by Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887. Burrell and Dale explain that “Bellamy’s book foretold of an industrial society transformed by the development of cooperative endeavor” (116). Howard’s designs were finally realized in 1903 in Letchworth, Hertfordshire UK, “Howard wanted to combine the advantages of town and country living, whilst avoiding the disadvantages of both” (firstgardencity.co.uk). According to the First Garden City Heritage Museum, “many of Howard’s ideas were incorporated and developed during the building of Letchworth Garden City. Housing in the town was to a high standard – most houses had large gardens, were often sited around grassed greens and many were carefully located to receive the maximum amount of sunlight. Letchworth Garden City attracted not only industries but people. Many found an ideological home in Letchworth’s tree-lined streets, and the Garden City became well-known for its unusual inhabitants, proponents of ‘The Simple Life’ who scorned the conventional dress of Edwardian England wearing sandals and smocks, ladies going without hats or gloves and children running around barefoot. Others were vegetarian, slept in the open air on specially-constructed balconies and had dew baths” (gardencitymuseum.org). Letchworth still runs today as originally intended and serves as a place of inspiration and education. The Heritage Foundation maintains the first Garden City through charitable endeavors that benefit the entire community.

The Howardian designs of Garden Cities even made its way into the United States, “the Radburn experiment in New Jersey in 1929 was meant to develop a complete new town where pedestrians and moving vehicles were to be completely separate”, however; this idea could not hold up “against the explosion of city populations in the early 20th century” (Burrell and Dale 116). These early attempts of combining urbanization with the unreserved nature did represent a strand of utopian thinking that has become popular once again. My initial question (What role does the garden play in utopian literature?) was answered in part, but the investigation lead to several other opportunities for research. Further inquiry in this area would explore the Garden Cities and how this design is being acclimated to contemporary town-planning charters like New Urbanism and Principles of Intelligent Urbanism .

Work Cited

Burrell, Gibson, and Karen Dale.

“Utopiary: Utopias, Gardens, and Organization.”

Utopia and

Organization. Ed. Martin Parker. The Sociological Review. UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2002. 107-127. Print

First Garden City. Letchworth Garden City Heritage Foundation. 18 February 2008. Web. 30 June 2011.

First Garden City Heritage Museum. “History of Letchworth Garden City.” Web. 3 July 2011.

Kakutani, Michiko. “A Familiar Cast of Fighters in a Final Battle for the Soul of the Earth.” The New York Times 14 Sept. 2009. Web. 29 June 2011.

Theroux, Marcel. "The Year of the Flood." Publishers Weekly 256.29 (2009): 119. Literature Resource Center. Web. 30 June 2011.