|

|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias

|

|

James Seth

4 July 2011

The Grass is

Always Greener: Fourierism and Socialist Utopias in Texas

INTRODUCTION

Influenced by Thomas More’s

Utopia and subsequent utopian novels,

Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia seems

also to have been informed by the ideas of Charles Fourier, specifically in

terms of communal living, returning to nature, aversion to monogamy and

traditional marriage, sexual freedom, and passionate living, in general.

Ecotopia portrays a Fourierian

community that rejects conventional notions of work, sex, and gender and applies

utopian concepts to a real place where they can be manifested, rather than a

fictional, far-away island.

Callenbach envisions a passionate, cannabis-using

community who work collaboratively and, despite their transparent emotions, very

efficiently. Callenbach’s novel performs the same work as socialist utopian

writers like Fourier, who viewed a politically liberal utopia as an actuality

and not simply an idea. Having been educated during his various travels in

France, Fourier was convinced that cooperation and involvement could lead to a

successful society. In the mid-nineteenth century, followers of Fourier traveled

to Texas and founded utopian settlements. This discussion post will attempt to

answer the following questions: Who was Charles Fourier, and why was he

influential? What was the mission or objective of socialist utopian communities

founded in Texas? Did these utopian communities prosper?

CHARLES FOURIER

Charles Fourier, born in

Besançon, France in 1772, was an influential writer and thinker whose works on

eliminating poverty and creating a cooperative society have made him a prominent

figure in literature, philosophy, and social activism (Denslow 169). Works such

as

Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées générales

(Theory of the Four Movements and the General Destinies) and Design for

Utopia: Selected Writings inspired

writers and philosophers such as Friedrich Engels, Roland Barthes, Walter

Benjamin and Nathanial Hawthorne to respond to his utopian ideas. The

following passage from Fourier’s Wikipedia entry explains his greatest societal

concerns and his utopian mission:

Fourier was deeply disturbed by the disorder of his time and wanted to stabilize

the course of events which surrounded him. Fourier saw his fellow human beings

living in a world full of strife, chaos, and disorder.[14]

Fourier is best remembered for his writings on a

new

world order based on unity of action and harmonious collaboration.[2]

He is also known for certain Utopian pronouncements, such as that the seas would

lose their salinity and turn to lemonade, and in a prescient view of

climate change, that the

North Pole would be milder than the Mediterranean in a future phase

of Perfect Harmony.[13]

Fourier was a proponent

of socialism, community living, women’s rights, freedom of sexuality, and what

was called by L Goldstein as “the liberation of human passion” (98). He

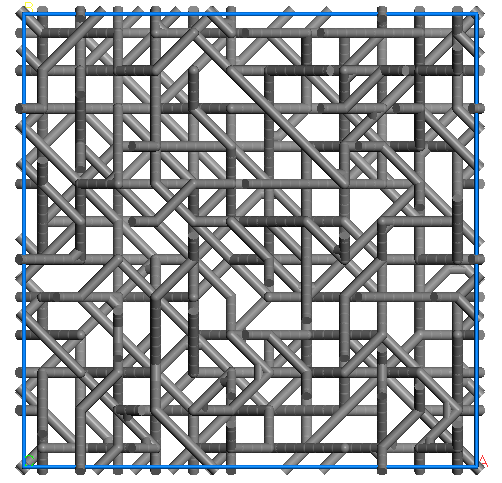

envisioned utopia as a communal society modeled on a phalanx, a military

formation used in Ancient Greece where soldiers would create a kind of mobile

fortress by surrounding the squadron with their shields. Fourier’s

phalanx-inspired communities resembled large-scale apartment complexes. The

buildings in his phalanx structure were called

phalanstères, or “grand hotels” in French, and were composed of “a center part

and two lateral wings” (Wikipedia). Corresponding to his ideas that marriage

inhibited possibilities for women, Fourier also felt that “the

traditional house was a place of exile and oppression of women. He believed

gender roles could progress by shaping them within community, more than by

pursuits of sexual freedom or other

Simonian concepts” (Wikipedia). Like other utopian writers such as

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Herland)

and Ernest Callenback (Ecotopia),

Fourier felt that women’s roles extended beyond the domestic sphere.

EARLY FOURIERISM IN TEXAS

Among those influenced by the writings of Fourier was Victor Considerant, a

French socialist who formed the utopian community La Reunion in Texas in 1855.

In France, Considerant was a musician, editor, and journalist, working with

Fourier on several newspapers and editing the journals

La Phalanstère

and La Phalange.

According to Jonathan Beecher, Considerant was one of several “visionaries who

combined rose-colored pictures of the geography, climate, and natural resources

of Texas with grandiose fantasies concerning the role that they themselves might

play in turning these attributes and resources to good use” (15). Beecher argues

that Considerant and other socialist contemporaries were idealistic about

applying Fourier’s ideas to a Texas community, overlooking the intensity of work

that was needed to create and sustain a Fourierian utopia. Before settling La

Reunion, Considerant had been involved in “radical political activities” in

France and immigrated in a time “immediately following the failed European

revolutions of 1848” (15). In a similar position as the English Puritans who

settled the first New England colonies, Considerant planned to create a model

community—a city on a hill, if you will—that would fully realize Fourier’s

phalanx structure and become a functioning, utopian society. A radical in his

native land, Fourier traveled to Texas to create what he felt would be the

prototypical Fourierian community. Beecher compares Considerant’s endeavor to

that of Icarian communist Etienne Cabet, concluding that Considerant’s failure

to make La Reunion the model utopian community “left the deeper mark on Texas

history” (15).

LA REUNION

La Reunion, founded by Considerant in 1855, was comprised of French, Belgian,

and Swiss Fourierists. Just one of 29 recorded Fourierist colonies, La Reunion

was a socialist utopian community that allowed everyone to vote and own private

property. The original community was comprised of nearly 200 colonists, who

settled near the Trinity River. The community worked building homes and

performing a variety of laborious tasks. In 1891, the Dallas Morning News

produced a lengthy article about the community, writing about their history,

occupations, ideological origins, and culture. The following passage from the

article depicts various social and cultural aspects of the community as seen by

visitors:

In the center of an

elevated plateau, this traveler would have seen a numerous company of laborers

busily engaged preparing to erect houses. He would have heard the ring of the ax

as it ate into the tree, the crash of the saw, the whir of the plane, the sound

of the hammer and the clink of the trowel as a stone was shaped. [. . .] He

would have heard these laborers talking as they worked, but talking in unknown

tongue. [. . .] He had seen a colony of Europeans engaged in the beginning of an

attempt to exploit the peculiar social theories of Francois Charles Marie

Fourier. He had seen a company of communists, sans culottes, if you will, with

their heads full of formulas engaged in an attempt to found a Utopia on the

prairies of Texas.

Regarding entertainment, the article reports that the

community had vocal classes, weddings, and holiday celebrations, including those

in honor of July 4th. Many residents of Dallas came to the Fourier

community’s celebrations. A Fourier society in Lyons even gave the colony a silk

flag to use at their celebrations; however, the flag was subsequently destroyed

by fire.

Despite their celebratory activities, La Reunion suffered a

great deal of hardships. This was largely on account of Texas’s unpredictable

weather, including a blizzard in 1856—just one year after settlement—which froze

the Trinity River and destroyed the community’s crops. While over 350 people

lived in La Reunion at one time, many residents began to leave the settlement

over the next ten years. By the turn of the century, La Reunion’s population had

sharply declined as members moved to other Texas areas or, in some cases, to

their European countries of origin.

In 1860, according to the La Reunion Wikipedia

entry, “the

nearby emerging town of Dallas incorporated La Réunion into its land area; the

remaining skilled colonists were absorbed into its specialized workers.” Many

colonists of La Reunion were assimilated in the workforce in surrounding areas,

and many of the colonists had specialized skills uncommon in Texas, such as

weaving, keeping shop, and, most notably, brewing. Though many colonists were

unsuited for agricultural labor, some of the remaining residents of La Reunion

in Texas formed the first brewery and butcher shops in Dallas.

OTHER SOCIALIST ACTIVITY IN TEXAS

According to the website

Labor History from Texas, the Meitzen

family of Halletsville was very active in the Texas Socialist movement. The

website states that the “Otto

Meitzen and Jennie Caroline Alpine Holmgren emigrated from Germany after the

repression following the failed revolution of 1848” and settled in Texas in

1850. The family was against slavery, but they chose to stay in Texas during the

Civil War, rather than moving to Mexico, which was a common decision for many

Texas progressives. Their son, Edward Otto, was particularly active in social

and political affairs; the website claims that “Edward Otto, who eventually

worked as a blacksmith, teacher, lawyer, publisher, and political leader [. . .]

was active in the entire succession of progressive organizations in Texas from

the Greenback Party in the 1880s, through the Farmer’s Alliance and the Texas

Populist movement, to the Socialist Party.” Edward—called E.O. in the

article—published progressive newspapers in Halletsville, the most famous being

The Rebel.

Though the paper stopped production after pressure from the United States

government, E.O. served as County Judge in La Vaca County and was “the

most successful Socialist candidate in Texas history when he gathered 11.7% of

the vote in the governor’s race in 1914.” Even after the Socialist Party

disbanded in Texas, E.O.’s children and grandchildren continued his progressive

mission, though the article does not give much detail on specific political

activities. The website states that “In 1914, E.O. Meitzen was shot by a sheriff

he had accused of “losing” important records concerning county monies. He

survived the shooting and other physical assaults and died in Houston in 1934 at

the ripe age of 79.”

WORKS

CITED

Beecher, Jonathan. “Building Utopia in the Promised Land:

Icarians and Fourierists in Texas.”

The French in Texas:

History, Migration, Culture

by

François Lagarde. University of Texas Press,

2003. Pg. 15.

“Charles Fourier.” Wikipedia. 30 June 2011. Web.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_fourier# cite_note-13

Dallas Morning News, January 25, 1891, Pt. 3, p.1

http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com /~jwheat/reunionart.html

Denslow, Van Buren. Modern

Thinkers Principally Upon Social Science: What They Think, and Why,

Chicago, 1880.

Goldstein, L (1982). "Early Feminist Themes in French

Utopian Socialism: The St.-Simonians and Fourier",

Journal of the History of Ideas, vol.43, No. 1.

“Phalanstère.” Wikipedia. 1 July 2011. Web.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phalanst%C3%A8re#cite_note-0

Roberts, Richard H. 1995.

Religion and the Transformations of Capitalism: Comparative Approaches.

Routledge. pp 90

Serenyi, P (1967). "Le Corbusier, Fourier, and the

Monastery of Ema", The Art Bulletin,

vol.49, No. 4.

“Socialism Settled in Texas.”

Labor History from Texas. Retrieved 1 July 2011. Web.

http://www.

labordallas.org/hist/reds.htm