|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias |

|

Kristine Vermillion

July 4, 2013

Garden Motif in Utopian Literature

Last semester in American Romanticism I spent a lot of time

studying the role of place in literature. My primary focus was on the wilderness

and its constant antithesis to a garden ideal. The setting of the story is of

significant importance in general, but it takes on another dimension in the

study of literary utopias. Utopias are the creation of an imaginary place. While

in the 1800s the vastness of the American wilderness was the literal place

fueling the minds and imaginations of Romanticism’s writers, in utopic works the

reverse is true in that the imagination fuels the creation of the place. It is

all about a place that is, as the word itself means, no place. Therefore the

garden theme and its antithesis of the wilderness are extremely important in

this genre. Leonard Lutwack in his book,

The Role of Place in Literature, explores the importance of place imagery:

“For all its adaptability to symbolical ends, place imagery is more tenacious of

concreteness and more impervious to attenuation than any other imagistic

materials. The most elemental orientation of a reader to a narrative text is

through its evocation of places. Setting is immediately positive and reassuring

until action and character are gradually unfolded” (Lutwack 37). The fact that

utopian fiction, especially the earlier ones, lack action and characters seems

to indicate that place is even that much more important, but Lutwack doesn’t

agree. Concerning place in utopias he says, “Augustine’s city and More’s

Utopia, from this point of view, are less interesting than the London of

Dickens because their settings have little relation to the social and spiritual

forms that thrive there. Utopias are not places at all but social systems, just

as the Fatherland is a political entity and not the land itself, which is better

represented in the image of Mother Nature” (Lutwack 37). I agree with Lutwack

that they aren’t as interesting and that they aren’t literal places.

However, I disagree with him because I think that place has everything to

do with the social and spiritual forms of the utopian project.

I have to admit that I was elated as I cracked open More’s

Utopia and almost immediately found

the garden vs. wilderness theme. First, the men had their conversation about

Raphael’s visit to Utopia within the walls of a home garden (1.1g). Then

immediately after that he describes the journey into the distant utopian land,

which he juxtaposes against a wilderness land. To get there, they had to travel

through “wild deserts and wildernesses, parched, burned, and dried up with

continual and intolerable heat.” In this wilderness land “all things be hideous,

terrible, loathsome, and unpleasant to behold; all things out of fashion and

comeliness inhabited with wild beasts and serpents, or at the leastwhile, with

people that be no less savage, wild, and noisome than the very beasts themselves

be.” But as they neared this utopian

haven, “all things begin by little and little to wax pleasant: the air soft,

temperate, and gentle; the ground covered with green grass; less wildness in the

beasts” (1.1h). The people of the land are said to take “great store by their

gardens,” and we are given a nice description of what their gardens were like.

“In them they have vineyards, all manner of fruit, herbs, and flowers, so

pleasant and so well furnished, and so finely kept, that I never say a thing

more fruitful nor better trimmed in any place” (2.4c)

It is only in these environs that the social structure More creates can

exist.

If you will recall with me, the same type of journey is taken

by Jeff, Van and Terry in order to get to Herland. The trip there required great

planning, preparation and supplies. It is a remote place that they have to

travel through forest and a dangerous marshy jungle to even come near. They were

in the wilderness, but thanks to their handy little plane, they were able to

scale the otherwise insurmountable rock wall and view and then land upon a

pristine land they initially describe as “a land in the state of perfect

cultivation” (1.130). From the ground

they later observe that “they all had pink houses.

The broad green fields and closely cultivated gardens sloped away at our

feet, a long easy slant, with good roads winding pleasantly here and there, and

narrower paths besides” (2.39). Then as

they walked down the road they observed “On either side a double row of trees

shaded the footpaths; between the trees bushes or vines, all fruit-bearing, now

and then seats and little wayside fountains; everywhere flowers” (2.48). Herland

is a garden paradise.

The same pattern is in

Ecotopia. To enter into Ecotopia Weston had to enter through “a

picturesquely weathered wooden fence, with a large gate, obviously little used”

(5). He then travels by super speedy

train nicely decorated with plants through wilderness land, enjoying views of

the wild animals. They then go through

the foothills around the city center which were aesthetically scattered about.

“The orchards, fields, and fences looked healthy and surprisingly will

cared for, almost like those of western Europe” (9).

Upon entering the city of San Francisco, this is what he sees: “What was

once Market Street has become a mall planted with thousands of trees.

The remaining space, which is huge, is occupied by bicycle lanes,

fountains, sculptures, kiosks, and absurd little gardens surrounded by benches”

(11). Later he observes that potholes

aren’t fixed but rather they are filled with flowers (12). While the gardens of

More and Gilman’s works look probably a bit more like English gardens in design,

Callenbach’s work envisions more of a free-form garden atmosphere, a kind that

is currently growing in popularity.

Before moving on to the research aspect of this post, I want

to take the time to point out the same pattern in

Oryx and Crake. While the pattern of

wilderness and garden is not as obviously laid out in Atwood’s writing, it is

still there nonetheless, and it is also given while on a journey from one land

to another like the other three. When Jimmy travels from Martha Graham to

Watson-Crick to spend the holidays with Crake, there’s a wilderness to garden

juxtaposition. While on the bullet train passing through the pleeblands Jimmy

sees a wilderness of sorts. “Rows of dingy houses; apartment buildings with tiny

balconies, laundry strung on railings … a huge pile of garbage. He glimpsed a

couple of trailer parks …. Everything in the pleeblands seemed so boundless, so

porous, so penetrable, so wide-open. So subject to change” (196). Once inside

the walls of Watson-Crick, however, he was in a “garden” land. “The extensive

grounds inside the security wall were beautifully laid out: the work, said

Crake, of the JigScape Faculty. The students in Botanical Transgenics had

created a whole array of drought-and-flood-resistant tropical blends, with

flowers or leaves in lurid shades of chrome yellow and brilliant flame red and

phosphorescent blue and neon purple. The pathways…were smooth and wide” (199).

The enclosed and landscaped design of the Watson-Crick compound contains all the

garden elements of a utopia, especially those of control, maintenance and human

endeavor. It is Paradice.

In these four pieces of utopian fiction the wilderness-garden

pattern is essential. The purpose of the research aspect of this project is to

see what others are saying about the garden theme and define what it lends to

the genre.

I am personally a gardener and this means that the subject is

obviously of great interest to me. In my opinion, the perfect vacation is going

to see a famous garden and spend time walking the grounds, and if possible,

finding a cozy bench and trying my hand at poetry. The rest of the year I spend

several hours every day working my own huge garden project. I love plants. I

just do. I am naturally drawn to the subject. Therefore it was interesting to

read the second part of Daniel Stuart’s midterm assignment titled “Utopia and

Gardening: An Investigation.” From the opening line, I could tell that Stuart

does not share the same outlook on gardens as I do. Therefore, a few comments he

made actually gave me insight that I naturally didn’t have. The first was that

he didn’t understand the draw to gardens and the second was that in utopian

societies it seems to be a prerequisite that you like gardening. He pointed out

that there really was no alternative. This feature is not appealing to many

people, and I can’t blame them. Gardening is no sissy sport! It requires hours

of backbreaking labor in the elements. The other main comment that Stuart made

that lent insight into the ideology of the utopia deals the pragmatic

justifications of the garden enterprise. The produce gained offsets the costs of

living and it brings people back into contact with nature in a way that is

synchronous with it instead of harmful. Stuart’s observations are insightful,

but they just barely scratch the surface of what I am after.

Jenna Zucha’s research post titled “The Garden of Utopia”

explored some of the aspects of this theme in the works we’ve read as well as in

Atwood’s sequel The Year of the Flood.

She asked a good question and provided an insightful answer regarding the

role of the garden theme in utopias:

So why is the garden so influential in utopian literature?

In part, it serves as an allegory for the actual process for creating and

maintaining a utopic state. The garden,

like utopias, attempts to bring organization and boundaries to an untamed

wilderness. Gibson Burrell and Karen Dale continue this idea in

Utopiary: Utopias, Gardens, and

Organization, by explaining that “Indeed, the wilderness seems the

antithesis of the garden: untamed, uncontrolled, unbounded, unpredictable, even

fundamentally unmanageable and disorganized” (121).

It seems impossible to control something that by definition is

uncontrollable. The concept of the garden

goes against nature, but it is a way of interacting with the uncontrolled in a

way that benefits all. The utopian ideal

functions the same way.

This analysis makes the connection between the work required in the maintaining and cultivation of a garden and how at every step of the process, the wilderness is barely kept at bay. Gardens require constant maintenance. Weeds are always a problem, and they signify that the chaos of the wilderness is always close at hand. This lends to the idea that utopias are always on the brink of becoming dystopias, and that to sustain them, they must be kept under constant maintenance and renewed and changed with the times. Zucha’s work led me to the book, Utopia and Organization, where the essay she found is located, and it was here that I spent the rest of my time researching.

In the same

essay that Zucha quoted above, Burrell and Dale start off by saying that:

“Space and place are fundamental to utopias. In the Christian

tradition, for example, the story begins in a paradisiacal garden and ends in

the Holy City, both obvious utopian images of placement.

Thomas More’s very play on “no

place’ and a ‘better place’ in

coining the word is clearly central to this and, as we will show, utopian

visions have a powerful link to geographical, physical, and spatial notions of

social organization” (106).

We were off to a good start since they are headed exactly

where I want to go. The overarching idea of the spatial organization of gardens,

their set boundaries and links to nature via beauty and productiveness are all

vehicles of imagery that lend to the utopian idea. The attainment of a utopian

existence is built upon the principles of protection, boundaries, the

beastliness of the outside and the beastliness of the inside, control, patterns

and formality (108). All of these principles “are predicated upon the securing

of organization in the face of disorganizing tendencies” (109). All of these

things are needed to keep the elements of the wilderness out. “Every utopia

attempts this boundary-work spatially. And so too does every garden” (109).

The idea of boundary is

essential to the garden imagery. They point out that man’s image of Paradise

always deals with this idea. The original garden after the fall was guarded

against entry. There were actual borders to the garden. The subsequent walls and

fences of gardens mark boundary lines demarcating safety and protection from

that which is without and the safety of that which is within. Then within the

garden there are more boundaries. There are hedges and topiaries that are

shaped. There are edges to garden beds. There are walkways and everything is

designed to control what is being grown within the confines of the space and

where. Mulching, weeding, pruning and watering practices all deal with

establishing acceptable boundaries for growth. The idea and place of the garden

in essence represent man’s best efforts at controlling nature and bending it to

meet his ends. In a utopian community the rules and standards operate in the

same way. They are designed to encourage and at the same time control human

growth and productivity. Burrell and Dale point out that a “topiary” and all of

the garden for that matter, “is an unnatural art since it seeks to control and

bend nature and to make it represent forms of human production” (111).

This is an interesting idea. Gardens do not occur naturally, yet they are

perceived as a human endeavor that brings humanity into contact with nature.

Without work, there is no garden. In the absence of boundaries there is no

garden. Without man, there is no garden. Apart from these elements there is just

wilderness, and once a garden is established, unless it is diligently maintained

it will return to wilderness at an astonishing rate. So the question really is

whether or not gardening is truly a natural human endeavor, which leads to the

question about the naturalness of the utopian endeavor. Regardless of the

answer, the wilderness is obviously the foil of the garden. Therefore, “the

wilderness is the foil of the utopia. For utopia is ultimately based upon some

form of humanism in its search for an ideal social organization” and the

wilderness is always there, barely kept at bay threatening chaos and destruction

(121).

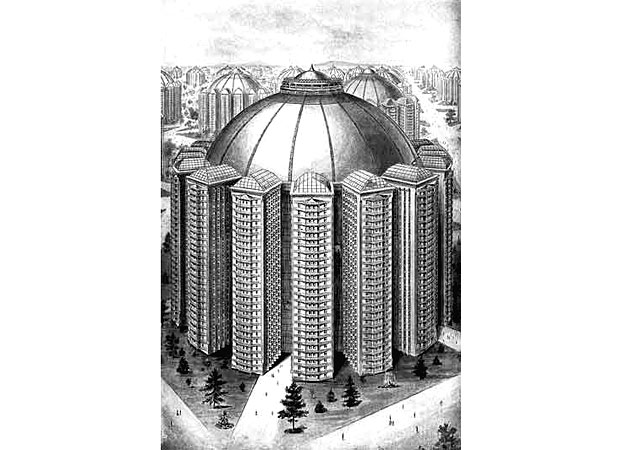

Burrell and Dale's essay offers several relevant points concerning garden

imagery that are worthy of further study, and the following paragraphs attempt

to summarize them. The essay and the book that it is found in are focused on the

organizational concepts behind utopian thought. The first point analyzes the

four distinct “zonal notions” that indicate different aspects of organizational

principles. The four zones are the city with its parks, the suburb with its home

gardens, the countryside with its fields and farms, and the wilderness which

lacks organization. The essay talks about each zone and offers great insight.

The authors also offer

insight and criticism into current trends in gardening and the commercialization

of it. This part of the essay discusses how market trends have “appropriated

‘nature’ for consumption. Gardens, we might suggest, have become a form of soma,

an ‘opium of the people’” (117). They talk about the huge garden centers, the

publishing media and their books and magazines, and the growing popularity of

garden TV shows that “assume the garden is a featureless ‘ground zero’ of

‘wilderness’ to begin with and is completely finished when the make-over crew

leaves” (117). They challenge and critique the trend that makes the garden less

of a place of subsistence and work but yet another place of “conspicuous

consumption”. In Oryx and Crake we

even get a picture of this in the extreme with the plants that are created and

the huge fake rocks that were designed to store and release water with the ebb

and flow of soil conditions: the ones that exploded when they got too wet

(Atwood 200). The experiments and the projects were pushed by the drive for

sales and profits. It was all about profit.

Another aspect of the

garden and wilderness imagery they discuss is the relationship it has with the

fertility of women. Women can be viewed as gardens—enclosed private places of

enjoyment and fertility. This garden imagery and the associated ideas of

boundaries and control lends well to the discussion of population control and

breeding practices that utopias deal with. “Thus the control of women’s

fertility is also closely connected with the control of race: the garden is to

be kept pure and not hybrid. Whilst it was men and women of all kinds who were

to be weeded out, sterilization was usually targeted at ‘the uncultivated

foulness’ of working class women” (123). This idea quickly leads to dystopian

nightmares.

In each of the last three

paragraphs are many ideas associated with this topic that could be explored

further. I think that each idea has merit and deserves further analysis into the

depths of garden imagery. The essay by Burrell and Dale offers a very insightful

discussion on the topic, and I am glad that I found it. I also appreciate the

opening essay in the same book by Martin Parker titled

Utopia and the Organizational

Imagination: Outopia. Parker is the editor of the book, and he seems to be

pretty skeptical of utopian literature and thought. He questions man’s

predisposition to social engineering and organizing, and in many places in his

essay lays much blame on the utopian impulse that drives man. I like the

definition of utopia that he offers: “utopias are statements of alternative

organization, attempts to put forward plans which remedy the perceived

shortcomings of a particular present age” (Parker 2).

Concerning the question as to whether or not the utopian project has

ended, he thinks that it is alive and well, but it is not labeled utopian, but

rather it is cloaked within the acceptable realm of “pro-market managerialism.”

The reigning ideology is the market and the utopian visionaries are those who

are working with how to properly organize and regulate the economic activities.

He wanders in and out of the local and global consequences of this trend and

then he ends with a statement that is also a good place for me to end. “Perhaps

this is for the best (that radical utopian visionary has been dismissed), and we

should just cultivate our own gardens, and not insist on tidying up everybody

else’s” (Parker 7). Parker’s perception into the current utopian/dystopian

tendency under the cloak of “the market” is one that shouldn’t go by unheeded

because it lends some insight into the social and spiritual forms in our own

present society and the utopian vision that is fueling them. We don’t want to

have to flee man’s attempt at a garden city, like Rand’s Prometheus and Atwood’s

Snowman, and take refuge in the wilderness. When the wilderness is more

hospitable and safer than the garden, something has gone terribly wrong.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. Oryx and Crake. New York: Anchor

Books, 2004.

Burrell, Gibson and Karen Dale.

Utopiary: Utopias, Gardens and

Organization. Utopia and Organization. Ed. Martin Parker. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing, 2002. 106-127.

Callenback, Ernest. Ecotopia. Berkeley, CA; Banyan

Tree Books, 1975, 2004.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Herland. (1915). Literary

and Historical Utopias Website for Dr. Craig White.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/UtopTexts/herland/herland.htm

Lutwack, Leonard. The Role of Place in Literature.

Syracuse, New York:Syracuse University Press, 1984.

More,

Thomas. Utopia. (1516) Literary

and Historical Utopias Website for Dr. Craig White

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/UtopTexts/MoreUtopia/utopiamore.html

Parker, Martin. Utopia

and the Organizational Imagination: Outopia. Utopia and Organization.

Ed. Martin Parker. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 1-23.

Rand, Ayn.

Anthem. (1938) Literary and Historical Utopias Website for Dr. Craig

White.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/UtopTexts/anthem.htm

Stuart,

Dan. “Utopia & Gardening: An Investigation.” Literary and Historical Utopias

Website for Dr. Craig White.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5439utopia/models

Zucha, Jenna. “The Garden of Utopia.” Literary and Historical

Utopias

Website for

Dr. Craig White.

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5439utopia/models