|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias |

|

Daniel B. Stuart

A Case for Utopia

Inspirational author Beverly Lewis is the prolific author of several

multi-volume series of novels centered around the Amish community. Story

archetypes for her books almost always involve a young teenage girl taking her

sabbatical years to reevaluate if she will continue with the Amish community or

separate from the society. After some serial conflicts in the outside world, the

girl almost always decides to remain with the flock, so to speak (Senseri). It's

an odd concept in today's world. Even in the highly conservative, spiritual

world of integrated Christian communities, the idea of living the lifestyle of a

nineteenth-century milkmaid seems foreign to most. And yet the stories represent

a utopia in a roundabout way, a civilization which has not only survived but

flourished. And yet, in the educational establishment, most literature within

the genre is concentrated in the dystopian medium. Secondary and higher

education exists for the purpose of furthering the knowledge and skill base of

the population but it also serves another purpose—to help individuals think for

themselves. Dystopian literature is taught in schools for much the same reason

that Greek tragic drama and classical fiction are taught. In a sense these texts

offer students a survey of the world around them, of the potential fallacies of

society, of the pitfalls of civilization and the problematic conditions inherent

in man and nature. Utopian literature should be taught for the same purpose.

Much of the logic and reasoning for incorporating dystopian literature

into the curriculum relies on the fact that students will be easily engaged.

Dystopian novels such as Lord of the Flies, Anthem, Hunger Games and

Handmaid's Tale exhibit characters and circumstances in which conflict is

readily available. There is always a regime or establishment wielding too much

power, the societal structure is too exploitive and corrupt, common man is seen

as futilely condemned to the service of the state, etc. It is therefore

inevitable that readers will identify with the rebel party, the oppressed

individual or group who rise up against the adversary for libertarian purposes.

Often these situations involve an abundance of action or suspense which in turn

sustains the attention of the reader. The problem, as educators see it, is that

utopian literature such as Looking Backward or Ecotopia might fail

to bring such drama to the reader. Additionally, what is the purpose of

instructing students on hopeless, impractical ideological cases when such

scenarios are implausible at best? Of course, much of these arguments are

already negated by the inevitable fact of intentional communities and utopian

societies which have in the past, are currently and will continue to operate.

Further reasons dystopian literature predominates curriculums have to do

with the dangers of conformity. Texts like Lord of the Flies, The Wave

by Todd Strasser and Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" offer readers a glimpse

into the programming of individuals and the risk of compulsory obligations. The

end result of all of these books is disaster in some way or sort. Yet the texts

clearly exist to encourage readers to not give in to peer pressure. Being secure

in one's identity is an attractive enough prospect for most, but absolute

ostracism presents a problem. The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier relates

the story of a young freshman student at a private, all-boys high school. It's

the tradition for upperclassmen at the school to have the freshman students sell

their candy door-to-door as a brief reminder of the institutional hierarchy. Of

course our protagonist is the conscientious objector, a position he maintains

all the way through violent personal attacks and numerous instances of

harassment (Cormier). The novel is not unlike the aforementioned texts and yet

all of these works are hardly speculative fiction. They exist in a conventional

reality; stories like this can happen and do. Jackson's 'Lottery' was actually

influenced by by Nazi propaganda and the Einsatzgruppen of the

concentration camps in WWII, a symptom in itself which presents a fascinating

dilemma as it still haunts so much of history and our present (Wilson, 87).

There are, inevitably, far more cases of peaceable, integrated communities that

operate under different circumstances and are far less prone to mob mentality.

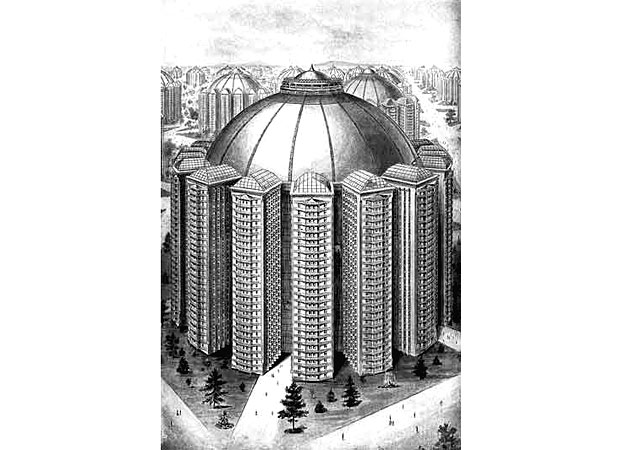

It may be the case that the word utopia itself is something of a

distancing stigma. Does a community have to be precisely regimented and work in

perfect cohesion without any problems in order to be successful, even to the

point of reaching an ideal? Probably not. In many ways, the concept of a utopia

is a more practically used idea than dystopia merely because so much of our

society is based on obtaining the best possible living standards. From fields as

varied as aesthetics and architecture to more objectively restrained disciplines

as civil engineering and demographics, utopia is not an infrequent term. The

interrelatedness of such aspects of our culture cannot fail to be evident to the

lay observer who lives in a modern society. Homes, subdivisions, neighborhoods

and towns are created for the purpose of intentionally accommodating the needs

of community divided into family units. Utopian literature and to a greater

degree, popular entertainment, caters to such trends. If dystopian literature

points out the flaws in society, utopian literature should at least be able to

engage readers in the issues which confront them on a daily basis and perhaps

even reinforce the values which are already in places.

Utopian books such as Ecotopia, Looking Backward, or Oryx and Crake

could also serve another purpose—to introduce students to other disciplines.

Ecotopia could enter the curriculum alongside environmental fiction

authors Barbara Kingsolver and T.C. Boyle. So much of our everyday lives are

becoming consumed with technology and medical ethics as Oryx and Crake

demonstrates. Books like these could introduced not just the ideas of

noncomformity, individuality, equality and personal responsibility but of the

interrelatedness of man and nature, of man and science. As mentioned, our

society is closely tied to aspirations towards utopian ideals and a more

perfected vision of life. So also does our ever-changing civilization integrate

aspects of the natural world and scientific innovation. In this way, utopia may

be seen as a more viable concept than dystopia which is more closely linked to

destabilization and anarchy.

So many dystopian novels and works of fiction begin in the midst of

unhappiness. A dysfunctional society is now the outcome of a failed state, a

millenial event, environmental crisis or oppressive regime. This is not the case

however in real life; at least not all the time. There are still places in the

world where people live without currency, live communally, work together and do

not rely on government assistance to support their needs. On a socio-political

level, utopian literary studies which concentrate on utopian ideas rather than

dystopian subject matter would likewise spur the debate on conservative and

liberal values. Students would be afforded the opportunity of critiquing the

vision of a working society rather than only surmising on what went wrong with

the dystopian one.

Admittedly, dystopian novels can be more fun to read, partly owing to the

fact that one's imagination can be exercised in a livelier way and escalating

conflict and action are the inevitable norm. Utopian literature is not so

homogenized as to prevent it from proliferating throughout the curriculum, both

as a literary topic and aspect of interdisciplinary studies. To study utopias is

to study humanity. For, after all, what is civilization but an extension of man.

To experience one man's vision for the perfect society is to collectively

observe the past and present, to incorporate aspects of psychology, politics,

sociology, geography and architecture among others. To learn of fictional

societies is one thing, but to observe and discover actual existing societies

like Ecotopia (the real one) and Twin Oaks, or to read about past experimental

communities of the Puritans, Quakers and Tolstoyans is to engage in a phenomenon

particular to our world and to us as individuals. To exempt utopian literature

as an educational tool while promoting dystopian literature would be to present

a one-sided argument for the fate of society. To include it would allow for the

dissemination of a greater wealth of knowledge and allow for a better discourse

of ideas.

Works Cited

Cormier, Robert. The Chocolate War. New York: Bantam, 1993.

Senseri, Marjorie. "New Waves in Inspirational Fiction" Library Journal.

Vol. 4. No. 6. May 2009.

White. Coursesite UHCL

Wilson, Gertrude. "Shirley Jackson." Contemporary Authors. New York:

Knopf, 1998.