|

LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias |

|

Jacob McCleese

Utopian Literature: Alluringly Gnarled Reality

How does one define literature? Previous to the eighteenth century this

definition was easy, literature was simply just a term to describe the written

word. This included poetry, fiction, essays, news reports, journals, and various

other mediums. After the 18th century, literary critics became

increasingly unsatisfied with this definition; it seemed too broad and

undefined. This dissatisfaction resulted in the creation of the Canon, the

standard by which all literature is measured, including utopian fiction.

However, utopian fiction is aimed at rejecting the dominant culture and

advocating for change. Most utopian fiction does not resemble the literature

found in the traditional cannon, at least not in a mimetic way. So, where does

this leave utopian fiction? Is it literature? Is it some form of perverted new

literature that requires a redefining of the canon? Studying utopian fiction

this semester has assured me of two things regarding this genre: 1) literature

adapts to person, place, and time; 2) literature must be aesthetically refined.

Utopian fiction exceeds both of these literary standards.

Literature is one branch on the humanities family tree. It exists in the

space between history and philosophy, collecting runoff from both disciplines.

Utopian fiction represents a perfect blend of literature, history, and

philosophy setting it a part from other forms of fiction. Utopian authors use

philosophy, in a rhetorically pleasing manner, alongside literary conventions to

create worlds that have enticed readers for decades. Utopian literature is a

true reflection of literary art.

Most people think of art as paintings hanging on museum walls. However,

art includes literature, sculptures, paintings, murals, and probably whatever

else artists want to present as art. Art is human expression, aesthetically

refined, and is most certainly seen in utopian fiction. A beautifully crafted

line, from Anthem, comes after

Equality has created fire. He writes, “We could not see our body nor feel it,

and in that moment nothing existed save our two hands over a wire glowing in a

black Abyss” (5.5). Ignoring the possible philosophy behind this moment, this

line shows Rand’s range as an artist. She takes the reader on a journey inside

him- or herself to a moment when the reader felt heroically empowered. As if the

reader just saved the world from utter darkness and freed his or herself from

blindness. Isn’t that a function of great literature? When a novel connects to

the human spirit and lifts it to a sublime realm, that novel deserves the title

literature. Rand’s line also hits on several human sensations. One can see the

light coming from Equality’s creation, feel the warmth exuding from the light,

hear the crackle and virgin spark, and relate to the elation that Equality

feels. This ability to trigger sensations is another mark of a great writer.

One sensation that many utopian novels trigger is sound, and they do this by

creating music with their words. Music is a blend of component parts, notes,

working together to create harmony. Separately, music notes are just noise

(listen to a child learning scales), but together they produce one of the most

unique expressions of human creativity. Literary expression is very similar. As

I write this next line, I’m thinking about how it sounds out loud, but there is

nothing particularly musical about it. This is not overly concerning given the

purpose of this essay; again, all writing is not literature. However,

Revelation, the great grandfather of utopian texts, is very musical. Here’s one

of my favorite lines, “And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude,

and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty thunderings, saying

Alleluia: For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth” (Revelation 19:6). Listen to the

melody created with this line. The author builds this line like a musical

crescendo, going from many voices, to many waters, and ending with thunder. The

repetitious “m” sound (multitude, mighty, many, omnipotent) provides this line

with a musical unity. This line is hitting on all cylinders on the scale of

musical literature and pleases the need for familiarity in literature.

Also, this line creates a picture. Most people know what a large room of

people speaking at the same time looks like and crashing waves are also a pretty

universal sight. Thunder creates an interesting visual ambiguity. Does one

picture torrential rain, trees being blown about by a mighty wind, or

illuminating flashes of lightning? Whatever the reader imagines, these images

are universally appealing and emotionally stimulating. Painting with words is

another common literary feature practiced in most of our utopian texts. The land

in Herland is described as, “a land

in a state of perfect cultivation…an enormous garden” (1.130). Hythloday, in

Utopia, describes the gardens as,

“Well ordered…finely kept that I never saw gardens anywhere that were both so

fruitful and so beautiful as theirs” (2.4c). Both descriptions place readers in

a perfect world, a serenely, elevated plane that makes readers more receptive to

the author’s assertions. It really is a brilliant literary technique.

Creating images with words appeals to all readers, especially when those images

are of nature. Everyone appreciates natural beauty. Large open spaces elicit

thoughts of eternity, vast space, and something beyond the bounds of the

corporeal realm. This is an important part of literary expression. Literature

has the unique ability to exist both spatially and temporally. Spatially,

literature exists on the page, of course. Yet, as the above examples show,

literature is not confined to the space between the front and back cover of

novels, or of page margins. All the utopian authors read throughout this course

use their literary abilities to tap into readers’ imaginations and take them

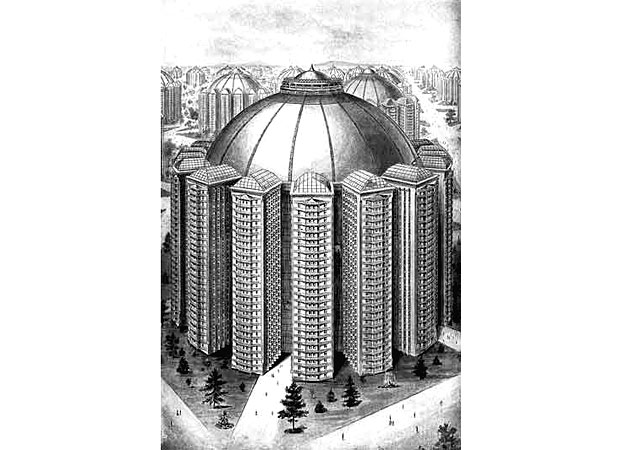

beyond pages and ink into forests, monolithic buildings, and on a tour of

intricate human societies.

Space has no hold on utopian literature, and time cannot hold utopian authors

down either. Literature, as stated earlier, has a historical element to it. The

difference between the two disciplines is that literature is free to create its

own history. More’s novel has many allusions to actual European traditions, but

the author fabricates many of Hythloday’s assertions. Utopian literature allows

and encourages variations in the flow of time to accommodate the author’s

purposes. This is why California drifting into the Pacific Ocean, in

Ecotopia, is not decried as a

temporally improbable occurrence.

Utopian literature does not have to measure up to the canon, but it does. Utopian fiction has all the fixings for great literature and the mounting interest of the populace. This genre does not sit in lofty places, like poetry, or present itself like a classical must read, like many novels; instead utopian novels are more accessible to non-English majors. The reading difficulty is by no means diminished, but the familiarity of many utopian texts invite readers to dive in and partake of the aesthetically pleasing utopian worlds.